What does it mean to be alone?

Catherine Allerton

[Publisher’s note: I am pleased to announce that, as of this issue, Catherine Allerton has become the co-editor of Anthropology of this Century. To mark this, we publish here one of Catherine’s articles that was originally included in Questions of Anthropology, a volume edited by R. Astuti, J. Parry & C. Stafford. This is by kind permission of the original publishers, Bloomsbury and the LSE Monographs on Social Anthropology.]

In this paper I want to discuss what it means to be ‘alone’ in particular ethnographic and historical contexts by considering the status of unmarried women. As countless instances in music, film and literature indicate, the spinster is often viewed as an icon of loneliness. Indeed, despite (as we shall see) fairly high and consistent rates of non-marriage amongst both men and women, the never-married woman has long held a problematic status in much of Euro-American culture. Images associated with the word ‘spinster’ are largely negative (Franzen 1996), perhaps explaining why the term is to no longer appear in official British marriage registers. In literature, spinsters are ‘old maids’ who were never chosen, portrayed by poets as ‘maidens withering on the stalk’ with a ‘tasteless dry embrace’ (Linn 1996: 70). Perhaps the best-known recent example of the ‘problematic spinster’ genre is Bridget Jones’s Diary, the book and film of which have both been enormously popular. The eponymous heroine is a thirty-something single woman, who sings along desperately to ‘All By Myself’ and can’t wait to get hitched to save herself from an overbearing mother and a faltering career. Contemporary Bridgets who need a little self-help in finding their man can choose from an array of popular books, where titles aimed at single women eclipse those aimed at men. These include: Why men marry some women and not others: how to increase your marriage potential by up to 60 per cent; The rules: time-tested secrets for capturing the heart of Mr Right; and the intriguingly academic-sounding Find a husband after 35: using what I learned at Harvard Business School.

But why should this be? Why should an unmarried woman be considered more ‘alone’ than an unmarried man? Why, in the words of the historian Olwen Hufton, should a spinster be seen as a ‘sempiternal spoilsport in the orgy of life’ (1984: 356)? Do all cultures see unmarried women as problematic? What does it mean to say that someone is ‘alone’ in different cultural and historical contexts?

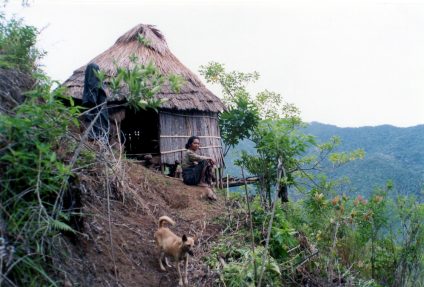

Photo by the author

My ethnographic point of contrast with the popular Euro-American view of the bitter ‘old maid’, is the region of southern Manggarai, in the west of the Indonesian island of Flores. In the two connected villages where I have carried out fieldwork, there are large numbers of older women who have never married or had children and who, I am quite sure, have no intention of ever doing so. These women vary enormously in appearance, health, personality, family set-up and socio-economic position. However, they are never the subject of ridicule within the village, nor are they considered frigid busybodies or women in a dangerous, anomalous position. Although people talked about marriage proposals that these women might have received in the past, they did not think that they ought to be married. Very few of these women ever expressed to me any kind of yearning for the married state and neither did their parents hope they would find (in the words of many worried British mothers) a ‘nice young man’ to ‘settle down’ with. If there was a Manggarai version of ‘All By Myself’, these women would not be found singing it.

In this paper, I want to try to do two different things. Firstly, I want to try and make sense of why so many women who I know in southern Manggarai have chosen to remain single, and why for the most part this is an unproblematic choice. Secondly, I want to compare this contemporary situation with a range of ethnographic, historical and demographic literature in order to think about the status of unmarried women across time and space. Why do some societies have near universal rates of marriage? Why, in other societies, do 20 per cent or 30 per cent of the population remain unmarried? What factors influence the acceptance, rejection or ridicule of unmarried women? Are unmarried women everywhere thought to be alone and lonely, awaiting the arrival of Mr Right?

Photo by the author

Anthropology has spawned various ‘classic’ debates on marriage, including of course the issue of the impossibility (in the face of the levirate, female-only and ghost marriage) of ever coming up with a definition in the first place. However, whilst the latter debate focused on the question of whether, once marriage had been defined, it could be said to exist in that form across all societies, anthropology has rarely asked the question of whether marriage is universal within particular societies. One notable exception is the work of Jack Goody, particularly in Production and Reproduction (1976), where he compares a situation of near-universal marriage in Africa with historically high rates of non-marriage in (Western) Europe, linking the latter with the existence of distinct economic or religious roles for the unmarried as well as Europe’s system of ‘preferential primogeniture’. The impact of such a system of inheritance, in particular with regard to the creation of a class of permanent bachelors, has been explored by anthropologists both ethnographically (cf. Arensberg 1937; Bourdieu 1962; Scheper-Hughes 2001) and historically (Goody 1983: 183-4). Nevertheless, in non-European settings, it has still often been assumed that unmarried adults are ‘almost entirely limited to the widowed, the maimed, the deformed, the diseased, the insane and the mentally deficient’ (Mead 1934: 53). I wish to contend that this is very far from the case, and that we need to be careful about assuming that marriage is always an essential rite of passage on the road to non-European adulthood, or that high rates of marriage necessarily correlate (as many demographers assume) with ‘traditional’, agrarian or even ‘patrilineal’ societies.

The universality of marriage

To the anthropologist accustomed to fine-grained distinctions between different groups living on one smallish Indonesian island there is something rather bracing about demography and ‘population studies’, where the nation-state and its statistics reign supreme. However, demography, backed up with a judicious dose of ethnography, does provide a useful starting-point for showing the cross-cultural variation in the ‘universality’ of marriage. The broadest contrast drawn in the demographic literature is between a ‘European’ versus an ‘Eastern European’ or simply a ‘non-European’ marriage pattern. J. Hajnal (1965) was the first to note this contrast, arguing that the ‘European pattern’ was marked by, firstly, a high age at marriage, and, secondly, a high proportion of people who never marry at all. To take a random, alliterative example, in Sweden in 1900, 80% of women were still single at age twenty to twenty-four, with 19 per cent remaining single at ages forty-five to forty-nine (the time at which Hajnal considers a woman to be permanently unmarried). By contrast, in Serbia at the same time, only 16 per cent of women were still unmarried at ages twenty to twenty-four, and by ages forty-five to forty-nine the proportion had dropped to only 1 per cent.

The ‘European’ pattern that Hajnal and others note is interesting for a number of reasons. Firstly, it disproves the assumption that lower rates of marriage in Europe are the result of urbanisation or industrialisation. The high proportion of unmarried persons in western Europe seems to extend back at least as far as the seventeenth century and possibly even earlier (Hajnal 1965: 134; cf. Goody 1983). Secondly, it is intriguing that spinsters have frequently been the target of suspicion, derision and witchcraft accusations (Bennett and Froide 1999: 14) despite the fact that unmarried women and men have long been a feature of the European kinship landscape. Thirdly, from roughly 1940 onwards, this ‘European pattern’ changed dramatically, with both men and women marrying more frequently and at an earlier age than in previous recorded periods (Hajnal 1965: 104; Dixon 1971: 230). This was also true of the United States, where the generations of women born between 1865 and 1895 had the highest proportion of single women in US history, a situation that had changed significantly by the late 1920s (Franzen 1996: 5-6).

In both Hajnal’s and other related work, the ‘Eastern European’ pattern of lower age at, and near universality of, marriage, is extended to most non-European countries. Dixon reports that, based on data from around 1960, South Korea, India, Pakistan and Libya in particular all showed an ‘amazing facility for marrying off their female populations’, with other Asian and Middle Eastern societies not far behind (1971: 217). However, Hajnal’s link between age at marriage and rates of marriage has been disproved by the example of Japan, which for over 400 years has had a pattern of relatively late age at marriage combined with very low rates of unmarried persons (Cornell 1984: 327). At the other end of the scale, Ireland continually reappears as a country with low rates of marriage, particularly for men: in 1960, 33.6 per cent of men aged forty to forty-four remained bachelors, compared to only 0.3 per cent in South Korea (Dixon 1971: 217). Nancy Scheper-Hughes has described how, in 1960s and 70s Ireland, these bachelors were recognized as ‘saints’ for looking after the family farm and their parents, but also how they were highly susceptible to being institutionalized with schizophrenia (Scheper-Hughes 1979).

To what extent is Hajnal right to extend the ‘Eastern European’ pattern to Asian countries? Certainly, the apparent universality of marriage in Asia seems to be backed up by the ethnographic literature. Rozario (1986) argues that rural Bengali women not married by the time they turn twenty are considered unmarriageable; these women then exist in a permanently liminal, ambiguous state since they have not been through the rite of passage which transforms a ‘girl’ into a ‘woman’. In Japan, failure to marry has carried ‘severe implications of immaturity and lack of moral responsibility’ (Goldman 1993: 196) and in Taiwan, the ghosts of young women who die unmarried are thought to cause misfortune for their families until granted proper status as a wife and mother through marriage to a living man (Harrell 1986).

However, it is interesting that the most striking of these ethnographic cases should come from East and South Asia. More recent demographic literature has stressed the considerable variation concealed by any idea of an ‘Asian marriage pattern’ (Smith 1980). In particular, there seems to be a notable difference between South and Southeast Asia, two regions that mark, respectively, the earliest and latest average female ages at marriage of the ‘developing world’ (Jensen and Thornton 2003: 10). In Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan, marriage remains virtually universal for women (Dube 1997: 109). The notable exception here is Sri Lanka (the ‘Ireland of Asia’), which has long had a far lower marriage prevalence than its South Asian neighbours (Jones 1997: 73). In Southeast Asia, the marriage pattern is more varied, both within and between nations. The Philippines, Thailand and Burma have higher than average celibacy levels for women (Smith 1980: 75), partly because both Buddhism and Christianity have allowed for the theoretical possibility of a woman remaining single (Dube 1997: 109), also a relevant factor in the Sri Lankan case. By contrast, the statistics for Indonesia have tended to report close to universal marriage rates (Jones 1997: 74).

In the case of Indonesia, though, it seems likely that national figures mask considerable regional variation, and tend to be skewed by the particular marriage pattern on Java, which has historically been characterized by early and universal marriage (Boomgaard 2003: 203). The eastern and southeastern islands of Indonesia have long had a higher female age at marriage than Java (Smith 1980: 69) and Boomgaard has concluded that outside of Java, marriage in Indonesia was probably not universal before 1850 (2003: 197). This suggests that significant numbers of women not marrying is not necessarily a new phenomenon in the region. However, what is interesting is that, since 1960, Southeast Asia has seen ever-rising rates of non-marriage, with far greater proportions of unmarried people in cities (Jones 1995: 192).

Who is an unmarried woman?

As anthropologists know, defining the married and unmarried in any one society may sometimes to be tricky. Defining such categories cross-culturally is even more difficult. Although in certain societies, widowed, divorced and never-married people face similar stigmas (Krishnakumari 1987), in others there are clear differences between these statuses. In this paper, I am concerned only with women who have never been married, not with widows or the divorced (who, in any case, are fairly thin on the ground in Catholic Flores). What term to give such women is clearly a problem, given the pejorative connotations of the word ‘spinster’. The precise technical term for the unmarried state is ‘celibacy’, deriving from the Latin caelebs, meaning ‘alone or single’ (Bell and Sobo 2001: 11). However, the everyday usage of ‘celibacy’ implies abstention from sexual relations, something clearly not the case for all single people, although definitely relevant to the unmarried on Flores. In this paper, when I refer to the ‘unmarried’ I mean those single people who have never married; I also sometimes use ‘singlewomen’ to refer to never-married rather than widowed or divorced women. I should stress that I am also speaking of women who have no children, although I recognise that in many societies unmarried women can be mothers too. Indeed, this raises serious issues of the comparability of the unmarried in different contexts since, in the West, the declining incidence of marriage has been largely offset by ‘de facto relationships’, something that does not yet appear to be the case for Southeast Asia (Jones 1997: 70; cf. Tan 2002).

Perhaps the most crucial issue with regard to defining singlewomen is the age at which ‘spinsterhood’ can be said to be permanent. Although Hajnal takes the numbers remaining single at ages forty-five to forty-nine as an indication of the numbers who never marry at all (1965: 102), in many societies the age that marks the onset of permanent single status may be considerably younger. This age is also frequently lower for women than for men. Rozario reports that while a man in rural Bangladesh can remain unmarried until he is thirty-five or even forty, women should be married by the time they are twenty (1986: 262). Similarly, Sa’ar argues that whilst demographers sometimes use twenty-five as the age from which a woman is considered unmarried, for Israeli-Palestinian girls twenty is a better marking point (2004: 16). In Manggarai, people have to be eighteen before they can be married in church, though priests say they prefer couples to be in their mid-twenties, something which is generally the case. Some women even marry as late as twenty-eight or twenty-nine. However, I do not know any cases of women who have married once they are over thirty and I have therefore taken this age as a rough cut-off point between what Bennett and Froide (1999) term ‘life-cycle singlewomen’ (those who do eventually marry) and ‘lifelong singlewomen’. I should stress, though, that since very few people know their date or even year of birth, I have had to estimate many women’s ages.

Singlewomen in Manggarai

My fieldwork in western Flores has been conducted with a community of subsistence cultivators and coffee farmers split between a highland, origin village called Wae Rebo and a lowland, road-side village called Kombo. In 1997, the population of this dual-sited community was roughly 480, although it has grown considerably since then. In 1997, there were 147 adult women in the community (defined as those over sixteen), of whom roughly 44 per cent were unmarried (sixty-five individuals). Some of these unmarried women were, and others probably still are, ‘life-cycle singlewomen’, that is, women who will eventually marry. Between 1997 and 2005, six of these women married (one of whom subsequently died in childbirth). A few others have temporarily left the village, either to move to look after the children of their white-collar brothers, or to work in shops in the towns of Flores. However, in 2005, thirty-seven of these original sixty-five women were over the age of 30 and could be said to be permanently single. In addition, a number of women who in 1997 were in their late teens or early twenties are now approaching the age by which, if they have not married, they are likely to remain single. When I returned to the community in 2001, Les, a woman in her mid-twenties, referenced her single status by exclaiming: ‘Oh, Auntie Kata, you come back to see us and here I still am!’ When I saw her again in 2005, she seemed to have accepted that she might not marry, and made no such jokes about it.

Rather like late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century England, then (Sharpe 1999: 209), roughly 25 per cent of the adult women in this community could be said to be ‘lifelong singlewomen’. However, this high rate does not extend to adult men, for whom marriage, even though it may be delayed to their thirties, is nearly universal. Wae Rebo-Kombo has only three true bachelors and of these, only Agus, a man in his late forties or early fifties, seems to have consciously chosen not to marry. The other two men have moderate to severe learning difficulties and are not expected by their families to marry. There is also a widower in his fifties whose wife died childless soon after their marriage and who, unusually, never remarried. What is significant is that both this childless widower and Agus are seen as rather odd individuals, either (in the case of the widower) inappropriately lewd with women or (in the case of Agus) impossibly shy and nervous. Actually, I think that Agus, although he is mocked for being ‘scared of women’, is well liked in the community. He is an extremely gentle and polite man, and treats his hunting dogs with the sort of kindness that is normally absent from Manggarai-canine relations. However, he is undoubtedly a ‘loner’, never joining in with older men as they sit chewing betel quids together or drinking coffee at meetings. The widower is similarly absent from everyday communal life and I have never met him personally.

By contrast, Wae Rebo-Kombo’s large population of unmarried older women are extremely visible and vocal in communal life, and are rarely subject to the kind of whispered ridicule reserved for these two older unmarried men. Unlike the ‘somber mass’ of Béarnais bachelors described by Bourdieu, these women do not necessarily feel themselves to be ‘unmarriageable’ (2002: 111; translation in Reed-Danahay 2005: 122-3). The oldest women in this group are in their fifties, and are addressed using the Indonesian term Tanta (‘Aunt’), since their lack of children prevents them from taking on the teknonyms used to address other older women. Significantly, there are no unmarried women in their sixties, seventies or eighties, and the narratives of older women reveal a past situation where women married at a younger age and had to accept the choices of their elders. This suggests that a once-universal female marriage rate has undergone significant change in the last thirty or forty years, prompting two key questions: why should this change have occurred, and how does this situation square demographically with universal marriage for men? Undoubtedly, a key influence has been the Catholic Church, which has pushed for marriage at a later age, stressed the necessity of a free choice for both bride and groom, and which has discouraged practices familiar to anthropologists as the ‘levirate’ and the ‘sororate’ (marriage to a deceased spouse’s sibling). At the same time, the creation of universal primary schooling has also opened up new opportunities for women, particularly bearing in mind the very strong relationship between improved education and female marriage patterns in Indonesia (Jones 1997: 60). Economic factors are also relevant: the introduction of machine-spun, synthetically-dyed cotton in markets in Manggarai removed the necessity to engage in lengthy processes of hand-spinning and dyeing and meant that women could concentrate on weaving, producing increasing numbers of textiles for sale. Male (but not female) migration is also becoming more common, reducing the number of potential marriage partners for women of marriageable age.

Explanations of why women remain single

Despite the broader demographic trends that have influenced the contemporary situation of singlewomen in this community, I want to devote some time to exploring local-level explanations of why so many women remain single. This is not only because these explanations are extremely revealing, but also because even more general demographic trends cannot explain why the percentage of singlewomen appears to be so high in this case.

One issue, of course, is the extent to which this village is something of a freak. This was suggested to me by various outsiders, who argued that it was the remoteness of Wae Rebo that had caused its high rates of unmarried women. Indeed, one outsider described these women as having ‘crippled blood’ (dara péku), an image which conveys both the criticism that these women do not travel to enough social events to meet men, and the general sense that their blood will not ‘walk’ down to the next generation. However, I am inclined to treat the ‘freak’ view with considerable scepticism. Wae Rebo is no more isolated than many other villages in rural eastern Indonesia, and I was certainly always aware of unmarried women when visiting other Manggarai villages. Older, unstigmatised, unmarried women also seem to be common in other areas of eastern Indonesia, such as among the Lio of east-central Flores (Willemijn de Jong, personal communication), and amongst weavers on the island of Sumba (Forshee 2001).

Unmarried women in this community are, of course, aware of external critiques of their position. Indeed, the suggestion that Wae Rebo women might have ‘crippled blood’ was recounted to me in a suitably outraged fashion by my friend Nina, an attractive woman in her late thirties whose comments that she felt ‘sick to her stomach’ (luék tuka) in contemplating a particular man’s moustache were a reflection of her decidedly misanthropic tendencies rather than any general antipathy to men. Like many unmarried women, Nina was happy to reflect on her own life choices, and to joke about being a ‘nun’ or preferring a radio to a husband, but was never very interested in more sociological reflection on unmarried women as a ‘category’. Those within the village who do engage in such reflection tend to be married women who have moved to Wae Rebo-Kombo to live with their husbands. These women, who are usually very fond of, and grateful to, their husband’s unmarried sisters and aunts, will sometimes speculate on possible explanations for these women never having married. Had people made a kind of anti-love magic to prevent men wanting to marry these women? Had their fathers prevented them marrying because they wished them to stay at home? Or were these women, quite simply, scared of childbirth?

Other explanations as to why these women never married betray a tension between the idea of ‘singledom’ as an unfortunate fate of particular women versus the notion that these women have consciously rejected marriage. Certain women were thought to have remained single because of ill health, appearance or mental instability. However, Tanta Tina, an extremely striking and industrious woman in her late forties, was said to have had many different marriage offers, but to have been reluctant to accept any of them. In reflecting on their position, many unmarried women do themselves move between seeing their single status as either a fate beyond their control, or a definite choice that they have made. Two sisters, Anna and Regi, both described to me unwanted attentions they had received from men in the past, and yet both seemed agnostic regarding their single status. As Regi, herself, summed it up: ‘well, if a husband arrives, that’s fine, if a husband doesn’t arrive, that’s fine too’. Nina had also received marriage proposals in the past. She once stated, quite categorically: ‘I don’t want to receive anyone’s letter (of proposal)’; on another occasion, though, she said she would quite like to have children, but ‘the problem is there’s no father for them’ (masalah toé manga amén) and women, unlike men, ‘cannot go looking’ (toe ngangseng kawé) for a spouse. This final point is crucial, and points to the fact that changes in the arrangement of marriages have left women in a somewhat ambivalent position, no longer forced into unions they object to, but also lacking sexual independence or the ability to seek their own spouse in a situation where young men and their families are responsible for initiating the marriage process.

Interestingly, Nina’s own mother had been forced to marry her husband, and their marriage, which has produced four children, was a tense and argumentative one. It has always been my impression that both Nina and Meren, her older, also-unmarried sister, have been profoundly influenced by their mother’s forced marriage. They are both close to their mother but openly dismissive of their elderly father’s opinions, and they would frequently ask me questions about whether women in the Britain were forced to marry against their will. Meren, who is in poor health and chooses to live on her own in a field-hut away from the village centre, was perhaps troubled by their common single status, confiding to me that she had told Nina: ‘don’t feel you have to follow me’. However, the phenomenon of more than one sister remaining single was not confined to this family, but is also found in families where the parents had a more compatible marriage. Thus, amongst the community’s unmarried women, there are fourteen cases where at least two, and sometimes three or four, sisters have remained single together. In others, the presence of an older, unmarried aunt seems to have influenced the decision of at least one of her brother’s daughters to remain single. Indeed, what Hufton (1984) calls ‘spinster clustering’ – the cohabitation of at least two unmarried women – is a common phenomenon in Wae Rebo-Kombo. The house of Tanta Tina in Wae Rebo contains five older, unmarried women and at least three more younger, unmarried women. In this instance, the presence of industrious and successful unmarried aunts undoubtedly encourages young women to consider both marriage and spinsterhood as possible future roles.

The idea that being a spinster can be a kind of successful career is an intriguing one, unexpected in the ethnography of Asia, but well described in the historical literature on European ‘singlewomen’, contradicting ‘the demographer’s belief that the spinster would only too readily change her status’ (Sharpe 1999: 209). Manggarai singlewomen may state that they cannot marry and leave the village because they ‘love my mother’ (momang ende) or ‘love the land’ (momang tana); just as frequently, though, they say that they need to ‘protect the economy’ (jaga ekonomi). Ekonomi, an English loan-word to Indonesian, is used here to refer to cash-crop farming, particularly of coffee, rather than subsistence agriculture. Several unmarried women have been given land by their fathers where they have planted their own coffee trees. When Anna and Regi did this during my fieldwork, I felt they were signalling a decision to invest in their unmarried future in the community. One singlewoman in her fifties, Tanta Tin, ran a rather profitable business selling paraffin carried over the mountains by her older sister’s son. Other unmarried women sell highland fruit at lowland markets and most, as throughout Eastern Indonesia, have an important ritual and economic role to play in the production of woven textiles. Indeed, the significance of weaving in this region, where women’s role as cloth producers is at least as highly valued as their role as wives and mothers (de Jong 2002: 272) is undoubtedly a key factor influencing the high status of unmarried women. Although married women do weave, once they have had a certain number of children, they often become too tired or busy to involve themselves in textile production, and it is, therefore, no coincidence that Wae Rebo’s most original and accomplished weavers were Tanta Tin and another unmarried woman in her fifties.

Unlike the more heavily-policed situation of unmarried women in some Muslim areas of Southeast Asia, singlewomen in Manggarai have a great deal of independence and freedom, a situation which only becomes easier as they age. By contrast, unmarried Manggarai men lack a clear role. Unlike his industrious spinster sisters, a man’s rejection of marriage is seen as evidence of his laziness, his fear of working to support a family. In many respects, unmarried women also have far more freedom, and are far less subject to the control of others, than in-married young wives. Unmarried women have control over the fruits of their own labour, and many stressed to me that if married, things would be far less ‘safe/ quiet’ (aman), since they would have to worry about their husband gambling or spending all of their money on cigarettes. The possibility of ending up unhappily married, saddled to a gambling man, is undoubtedly a major disincentive for these women to marry, given that in rural Manggarai divorce is impossible.

However, whilst such women may be critical of men as husbands, they have a somewhat different view of men as brothers. The comments of these women on the changes in kinship status that marriage brings have led me to conclude that these women would rather remain part of their brother’s family, working together with him, than experience the inevitable alienation involved in becoming a woé. Woé is a term that denotes both a ‘married sister or daughter’ and her husband’s family, the kind of term that is normally translated by anthropologists as ‘wife-takers’. Those who are woé remain permanently indebted to the natal families of their wives and mothers. However, the ultimate irony of the system is that, although it is the ‘gift’ of a woman that creates this debt, after marriage the woman herself becomes part of the group that must repay it. When her real or classificatory brothers decide to marry, she and her husband receive ‘requests for money’ (sida) and other assistance that they must always meet. Such requests are also made at the rituals that follow a death, irrespective of whether a group of woé have paid off their bridewealth or not.

One hot day in the highlands, during a siesta on my bed, Nina chatted to me again about why she didn’t want to marry. She said:

Life is different for married women, they are always really busy (sibuk-sabuk), they always have to find money to marry their brothers (laki nara). Whenever I hear a tape playing for a kémpu [bridewealth negotiation ritual] I feel really sad, because I think it could be mine, my own kémpu. A man has to treat his sister and mother well, but he can treat his wife how he likes – she is someone who has already been bought (ata poli weli).

Similarly, when I went with her sister to bathe at a river in the lowlands, Meren said:

After you are married, when your brother decides he wants to get married, you have to give a buffalo. But if you aren’t married, then you can just search together (kawé sama) with your brother, so that he can get a wife.

At the heart of this and other statements by singlewomen lies the profound understanding that a woman’s relationship with her brother (and, by implication, with her natal family) becomes quite different once she marries and becomes woé. If women remain unmarried, they do not experience such alienation but remain a key part of their parents’ and brother’s household. Certainly, it has always seemed to me that there are great advantages to a man in having one or two unmarried sisters in his house, and the relationship between children and their aunts can be extremely close, dispelling any assumption that unmarried women experience their situation as one of ‘childlessness’.

After she had told me about preferring to ‘search together’ with a brother rather than marry, I asked Meren, ‘Don’t you feel sad that you don’t have any children of your own?’ She replied: ‘No, because you can care for your brother’s children. Look at Tanta Tina in Wae Rebo. All of her brother’s children see her as just like a mother, because she has brought them up.

Tanta Tina, to whom Meren refers, had provided a highland home to all of her brother’s children, in the periods both before and after primary schooling (her brother lived in the lowlands and took care of the school-age children). Her role in the family was confirmed when one of these children, a young woman called Kris, sought to marry a man from the same community. Although Kris’s own mother was in favour of the match, Tanta Tina objected and it was, therefore, abandoned. This example shows that unmarried women’s role in their brother’s children’s lives goes beyond matters of practical childcare and even extends to the negotiation of marriage. They are, therefore, very unlike the European ‘maiden aunts’ who historically constituted a ‘reserve of domestic service’ associated with ‘female renunciation’ (Goody 1976: 59). Some older unmarried Manggarai women exert a powerful influence on family decision-making. One such example was Tanta Tin, who, since her elder brother’s death, had become the de facto household head of an extended family unit consisting of herself, her brother’s widow, his unmarried daughter and his two married sons. Tanta Tin once spoke to me about the love she felt for Maka, the youngest son of her deceased brother:

[When I look at him] it’s just like looking at my own brother. Ai, that’s still my brother. Yes, he’s replaced his father’s face. So I’m like this with him. If he is going far away and I don’t see him go, I feel very sad. Yes…very sad when he goes.

For Tanta Tin, Maka represents the living embodiment of his father, and her closeness to him means that she feels sad when he goes away. However, it also means that when the time came for Maka to find a wife, it was Tanta Tin who went to ask for a tunkgu or ‘joining’ match with Maka’s classificatory mother’s brother’s daughter, Sisi. Whilst Maka may have taken the place of her deceased brother in Tanta Tin’s affections, in ritual and alliance matters concerning the family, that place has been taken by Tanta Tin herself.

Women, siblings and being ‘alone’

Although this is clearly a very small sample of people from which to make generalisations for Manggarai as a whole, it would seem that women remain unmarried in this context for a range of different reasons. Fate certainly plays a part, as does a recent increase in male migration. I do want to stress, though, that for many women, remaining single is an active choice, motivated partly by a desire to retain an economically independent existence in their natal village, as well as a dislike of the possible implications of becoming woé to their natal kin. Of course, it is only a minority (25 per cent or so) of women who reject such alienation. Most are happy to embrace it, for the pleasures that sexual intimacy, children and life in a different village may bring. I realise that, by largely focusing on the reasons that women give against marriage, I have neglected the positive factors that motivate most of them to marry. However, this is partly because married women, even obviously happy ones, tend to have very little to say on this subject, no doubt reflecting the fact that, in some respects, marriage still remains a ‘given’ of social life. In particular, there is very little discussion of sex, unlike in the West, where Bridget Jones and other ‘problematic spinsters’ are often explicitly interested in problems of sexual availability and frustration. I do not profess to know how my unmarried Manggarai friends, living in a deeply prudish society, feel about a life without sexual intimacy, but my suspicion is that it is not foremost amongst their concerns.

The unproblematic status of unmarried women in this context, as well as the emphasis they themselves give to their role as sisters, brings to mind Sherry Ortner’s famous article on the sex/gender system in hierarchical societies (1981). Put very briefly, Ortner’s argument is that the apparently ‘high status’ of women in the cognatic/endogamous societies of Polynesia and Southeast Asia is because of the ‘encompassing’ nature of kinship in these societies, and the resulting fact that women are primarily defined as kinswomen (daughters, sisters and aunts). By contrast, she argues, in the patrilineal systems of India and China, women have a generally lower status since cultural emphasis is placed on their role as wives and mothers, and they tend not to be seen in terms of their ongoing value as kinswomen (1981: 399-400). Now, certainly, cultural definitions of female adulthood in terms of marriage and motherhood may well account for the almost universal rates of marriage in India and China. In the South Asian context in particular, the problematic status of unmarried women is often expressed in terms of the dangerous and polluting nature of their uncontrolled sexuality (Rozario 1986: 261). However, in the Southeast Asian context, the ‘high status’ of women as kin does not necessarily mean that a woman can remain unmarried. Strong ideological preferences for marriage are not necessarily the result of gendered concepts of purity and pollution. Nor, interestingly enough, does the high prevalence of marriage in South Asia necessarily result in marital stability (Parry 2001).

In many Southeast Asian societies, the sexes are frequently seen as ‘complementary’ rather than ‘opposite’, and married couples may therefore be seen as the basic productive units of society. For example, amongst the Buid of Mindoro, marriage is the ideal social relationship and forms the basic domestic unit; this means that although divorce is frequent, ideally no adult should remain single for more than a few weeks at a time (Gibson 1986). Similarly, amongst the Wana of Sulawesi, the conjugal couple is central to everyday and ritual life, and the assumption that people will marry is almost automatic (Atkinson 1990). Now, both these societies are cognatic and endogamous, conforming to Ortner’s vision of Southeast Asian (and Polynesian) social structure. However, although such systems are common across Southeast Asia, the region is also home (most notably in Eastern Indonesia) to societies that emphasise exogamous marriage and an ideology of patrilineal descent. Manggarai is one such society. What is interesting about Manggarai is that, although women share a characteristically Southeast Asian ‘high status’, and although they are highly valued as sisters and daughters, the exogamous nature of marriage means that it displaces them from their home. Indeed, it may well be the fact that women are valued both as wives/mothers (who leave their natal home) and as daughters/sisters (who remain in their natal home), that makes both marriage and singledom attractive prospects for a young woman. In this context, patrilineality does not necessarily lead to universal marriage.

Kinship is, of course, only one of the factors that may influence the perception of unmarried women. Another is the extent to which they are able to occupy a specific economic role (cf. Goody 1976: 58). It is worth remembering that the very term ‘spinster’ originally meant a female spinner of wool, and that it was only in the seventeenth century that it came to refer to a singlewoman, largely because many such women earned their living working as ‘spinsters’ (Bennett and Froide 1999: 2). Similarly, another term frequently used to refer to singlewoman, ‘maid’, references the frequent link between single status and employment as a servant (ibid., p.16). Throughout Eastern Indonesia, weaving offers women a ritually and economically important role that they can undertake independently of any male (de Jong 2002; Forshee 2001). The introduction of cash crops such as coffee, and the inheritance of land by Manggarai daughters from their fathers also gives unmarried women independent economic roles. Certainly, when viewed cross-culturally, the move away from an agrarian, subsistence economy does frequently open up new opportunities for women that may make ‘singledom’ a more attractive prospect. However, the extent to which men may feel threatened by this new independence varies. Allman describes how during the colonial period in the former Gold Coast, the introduction of cocoa as a cash crop led many women to establish their own farms, rather than labouring on the farm of a husband. This resulted in a temporary chaos in gender relations, with chiefs rounding up unmarried women over fifteen and not releasing them from prison until a man was named as their potential husband (Allman 1996). In the contemporary context, Ashante women traders may briefly marry and have children, but still express preference for independent trading, declaring that ‘onions are my husband’ (Clark 1994). Again, this raises the issue of the comparability of unmarried women cross-culturally, since apparently high marriage rates may conceal large numbers of women who effectively act as singlewomen. Ashante traders may be ‘married’ and have children but in many respects they act as independent single women. Similarly, in many different cultural contexts, uxorilocal marriages provide a way for a woman to remain in her natal village and retain a great deal of independence (Bloch 1978).

Having considered the differing status of singlewomen cross-culturally, and the complex economic, historical, religious and kinship factors that may or may not make marriage universal, I now want to shift the focus back to the nature of ‘alone-ness’. As the testimonies of my single friends have hopefully shown, unmarried Manggarai women are not perceived by others as ‘alone’, nor do they experience their situation as one of loneliness. When I tried to provoke a reaction in Nina, Meren, Anna or Regi by telling them of single British friends of mine who experienced ‘singledom’ as a somewhat lonely state, who wondered how they would meet ‘the one’, and who worried they would never have children, my Manggarai friends all looked rather blank and told me this was very strange. Singlewomen in this contemporary Indonesian context do not flinch at news of weddings and babies, they do not cry themselves to sleep listening to sentimental ballads, they are not the object of witchcraft accusations or undisguised contempt. They, thus, provide an interesting contrast with Western Europe where, despite a long history of high numbers of unmarried women, singlewomen are still often seen as both ‘alone’ and ‘lonely’. However, this does not mean that being ‘alone’ (hanang-koé or ‘only-little’) is not an extremely important Manggarai notion. Indeed, as I shall briefly describe, Manggarai people share what seems to be a general Southeast Asian fear and dislike of being alone (Cannell 1999: 153, 159).

Now, obviously in the course of everyday, productive, life – when a woman goes to collect vegetables from her field, for example – people may sometimes have to be alone, and this is accepted. However, there are certain activities that should never be performed alone. Perhaps the most important of these is sleeping, since the sleeping person is vulnerable to disturbing dreams or visitation by spirits. This is particularly the case immediately after a death, when the soul of the deceased may still visit its relatives at home. Bereaved houses are therefore always full of people, including young men who gamble all night to keep the house ‘lively’ (ramé). Those who make noises or talk in their sleep are always immediately woken up by others, and it is partly because of this that no-one should ever sleep in a house alone. If the absence of other household members leaves a person alone in their house, other friends or relatives will always turn up at dusk to cook supper and sleep together with them. Indeed, it is almost as important not to eat alone as it is not to sleep alone. A wife will always wait for her husband to return to the house from work in the fields, however late he is, before dishing up their shared meal, and a visitor will be saved the embarrassment of eating alone by a household member joining them, even if only to eat a small amount. Once, when I was visiting their house, two small boys were whingeing quietly about being hungry. In response, their great-aunt, Tanta Tin, dished them up rice and vegetables on two separate plates. However, the boys refused to eat. Tanta Tin then picked up the two plates and unceremoniously sloshed their contents onto a third, whereupon the boys ate happily using individual spoons. ‘Ah,’ she said indulgently, ‘they don’t want to eat alone’.

By contrast with the West, where the capacity to be alone is considered crucial to mature emotional development (Winnicott 1958), people in Manggarai view being alone as, at best, a temporary inconvenience and, at worst, a spiritually and emotionally dangerous state. This also links with a general negative evaluation of solitariness as a character trait. In particular, those who walk around alone at night are viewed as extremely suspicious, since shape-changing sorcerers operate during the dark, turning themselves into cats or other creatures in order to harm others. However, like those in Britain, Manggarai people do not apply the term ‘alone’ (hanang-koé) merely to actual, physical circumstances, but also use it as a more emotion-laden term to describe the more general situation of certain individuals. When used in this way, there are definite categories of people who stand out as being ‘alone’.

The most obvious of these categories might appear to be childless married couples. Certainly, in many ethnographic contexts, including amongst the Zafimaniry (Bloch 1993), it may not be a marriage ceremony as such which cements a couple together, but the birth of one or more children. Indeed, in many parts of the world, infertility may be a prime reason for divorce. Across Southeast Asia, children of both sexes are extremely highly valued and infertility is taken very seriously. However, the specific ways in which childlessness is dealt with vary. In Pulau Langkawi, childless couples frequently foster a child given to them by a sibling (Carsten 1997: 247). However, in Manggarai, neither divorce nor fostering are options for childless couples. This seems to suggest that the ‘alone-ness’ of childless couples is not so extreme or so threatening that it needs to be solved by other mechanisms. The childless couples that I knew in Wae Rebo-Kombo, with one significant exception, were not stigmatised or viewed as less-than-adult. They were fully involved with community life and, though they did not foster children, had an important role in the care of children of relatives or fellow house-members. The exception to this rule were an elderly couple who were spoken of antagonistically. However, this was not primarily due to their childlessness (indeed, the man was rumoured to have fathered various illegitimate children) but because of what people saw as their failure to contribute to collective funds for funerary and other rituals.

Two types of individual who are spoken of more frequently as being ‘alone’ are orphans and only children. An ‘orphan’ is considered someone who has lost either a mother or a father whilst young, and may be vulnerable to sickness caused by the love or interference of this parent from beyond the grave. Only children are, actually, extremely rare in Manggarai, partly because of high fertility rates, and partly because a man will tend to marry again if his wife dies whilst he is still young. One woman, Agnes, an in-married mother of seven, was an only child and this was repeatedly pointed out to me both by Agnes and others. Despite her seven children, Agnes would say ‘I’m really very alone’ (hanang-koé kéta kaku ga), as if stressing the poignancy of her lack of siblings in a situation where siblings are highly valued. Interestingly, within larger families, a single brother would also be considered ‘alone’, whereas a single sister would not. This is because, within a broadly patrilineal context, a man’s same-sex siblings (ahé-kaé) are crucially important both in everyday life and in the context of marriage negotiations and rituals.

A final category of people who are considered ‘alone’ are those who are outside of reciprocal exchange obligations. Within Wae Rebo-Kombo, villagers operate a system of pooling money and foodstuffs at certain ritual events, on the understanding that co-villagers share the responsibility for, for example, providing coffee to guests after a death, or cooked rice to accompany the meat at marriage rituals. There are also more specific obligations that operate between groups of male (real and classificatory) ‘siblings’ (ahé-ka’é). However, one family – an elderly man and his three adult sons – were considered to have ‘broken’ (biké) their connections with their wider ahé-ka’é because of a particular argument between two individuals in the past. This family no longer makes contributions towards events of their ahé-ka’é (any contributions they do attempt to make are always ‘pushed away’, tolak), nor do they receive help from others at the time of weddings, funerals or other rituals within their own family. Within the Manggarai context, then, it is people such as this who are considered to be most profoundly ‘alone’. Moreover, the crucial thing about this category is that the people in it are considered to have somehow chosen to be ‘alone’, unlike those others mentioned above, whose ‘alone-ness’ is largely a result of fate.

Being ‘alone’ is obviously a complexly gendered notion in many societies. As indicated at the beginning of this paper, in British society, it is frequently those who are ‘single’ (without a partner, whether or not they are married), and particularly single women, who are thought to be most ‘alone’. However, there is a kind of problem with the way in which using ‘single’ to refer to unmarried people in other cultural contexts somehow implies that they are on their own. I prefer to follow Goffman (1971), who uses the terms ‘singles’ and ‘withs’ to reference interactional units. Whereas a ‘single’ is a party of one, a person ‘by himself’, a ‘with’ is part of a party of more than one, whose members are perceived to be ‘together’ (Goffman 1971: 19). If we follow Goffman’s definition, we can help to see why unmarried women are not a problem, even in a context where (as for much of Southeast Asia) ‘alone-ness’ is problematic. The simple reason is that, although unmarried women may have a ‘single status’ with regard to marriage, in terms of wider social life they are most definitely ‘withs’, whether connected with another unmarried sister, their parents, or their brother and his children.

In Manggarai, as in much of Southeast Asia, it might be said that to be alone is not to be without a spouse but to be without a sibling. As we have seen, it is not the unmarried, or even the childless, who are thought to be most alone but those who, whether through fate or because of their own actions, are excluded from the benefits of siblingship. Male siblingship is, within this patrilineal context, particularly stressed. However, the examples of ‘spinster clustering’ amongst unmarried sisters, as well as the explanations that unmarried women give regarding their reluctance to become woé to their brothers, also show the significance of female and mixed siblingship. Interestingly, siblingship is also represented in another register in Manggarai, through various ideas about ‘body siblings’ (ahé-ka’é weki), also known as ‘spirits of the nape of the neck’ (déwa du’ang) or ‘angels’ (malaikat). Each individual is thought to have such a guardian spirit, and they are closely connected with that individual’s health, fate and happiness. On a number of occasions, I also heard unmarried women refer to such guardian spirits as their ‘husband from the other side’ (rona palé-sina), that is their spirit spouse. Not only does this connect with more general Southeast Asian tendencies to equate spouses with siblings (Carsten 1997: 92-4; Cannell 1999: 54-9), but it also suggests something of a paradox. In this context, ‘body siblings’ ensure that no-one is ever totally ‘alone’, as well as ensuring that even unmarried women do have some kind of spouse.

What, finally, of the issue of ‘loneliness’? Are those who are defined as ‘alone’ always ‘lonely’? This is clearly not always the case, as my example of the orphan Agnes, happily surrounded by her seven children, should prove. However, as I have discovered, ‘loneliness’ is a hard concept to research from a cross-cultural, anthropological perspective. A search of literature and internet sites overwhelmingly leads to two kinds of information: self-help and practical tips for university students and self-help and spiritual guidance for those of single status. A third area of concern appears to be the extent to which modern technologies, such as the internet, are actually increasing the incidence of loneliness in many societies. Perhaps, then, loneliness is not a cross-cultural notion of any value, but the product of specific historical and technological circumstances? In Manggarai, though people talk of themselves and others being alone, they do not talk of feeling ‘lonely’. Indeed, as I discovered during fieldwork bouts of homesickness, expressing ‘loneliness’ in this context is extremely difficult. There are simply not the words. However, does this mean that people never feel lonely? During my fieldwork of 2001, the wife of the elderly, childless couple I mentioned above died. Since this old woman had been the target of much suspicion, and since the couple were outside of reciprocal exchange obligations, very few people went to cry over the corpse, or to visit the house after the death, a terrible symbol of the couple’s social isolation. Shortly after this, though, people commented that her husband had started to make more social visits within the village. Was it possible, after all, that he was motivated to do so by loneliness?

Conclusion: marriage and ‘adulthood’

Gossip about forthcoming, previously scandalous or indefinitely postponed marriages must be one of the staples of fieldwork, wherever it is carried out. Equally, most societies would seem to be somewhat intrigued, surprised or disgusted by the marriage customs of their neighbours, provoking all manner of questions about human similarity and difference. People in Manggarai, though unaware of anthropological literature on the ‘matrilineal puzzle’, often chatted – with equal quantities of puzzle and amusement – about the marriage practices of the Ngada people to the east. How odd that it was men rather than women who had to leave their natal home after marriage… How strange that women could inherit land and houses… Side-by-side with talk about marriage histories and customs always went some speculation on the lack of opportunity or desire for marriage of certain individuals. As this paper has tried to show, there are several key questions that may motivate such speculation across human societies. Why don’t some women want to marry? Is that a natural thing or an abhorrence? Should women be forced to marry? Are unmarried women polluting? Are they alone? Should we pity them?

Although it is demographic literature that provides us with broad comparisons in the cross-cultural ‘universality’ of marriage, we can question many of the reasons that demographers give for such universality. Dixon, for example, argues that it is ‘clan or lineage systems and ancestor worship’ and an attendant compulsion to produce children to ‘strengthen the clan’ that causes the ‘stigma and shame’ attached to non-marriage and childlessness in ‘many non-Western countries’ (1971: 226). As this paper has shown, the existence of an emphasis on patrilineality, as well as a concern with the ancestors, does not necessarily lead to the stigmatisation of the unmarried state. However, lest I be drawn into too much demographer-bashing, let me end by making some criticisms of anthropology and, in particular, that area of the discipline concerned with ‘personhood’.

The influence of van Gennep’s (1977) model of rites of passage in the anthropology of personhood seems to have created a kind of unspoken assumption that, in many non-Western societies, marriage is an essential rite in turning people into full ‘adults’. This can be seen quite explicitly in certain comments of Margaret Mead:

While primitive societies vary in the degree to which they explicitly emphasize the point, to be socially mature is to be, among other things, married. Therefore, in most primitive societies such individuals are definitely social deviants… so that a discussion of their rather bizarre situation is irrelevant…’ (Mead 1934: 53).

Mead’s language here may be outdated, but I would argue that her assumptions are not. Anthropologists still frequently make over-hasty assertions that unmarried women are ‘anomalies’ or exist in a permanent state of ‘liminality’, somehow never reaching full adulthood. Yet why should we assume that all societies conceive of the road to adulthood as a kind of single, Van Gennep-like progression? After all, the ethnographic literature is full of powerful counter-examples to prevailing cultural emphases on marriage. In northwest India, and despite the strong cultural imperative to marry, girls may choose to become celibate sadhins, a name that associates them with a wider Hindu ascetic tradition, whilst they live in their natal homes as unmarried women (Phillimore 2001). Amongst Israeli-Palestinians, and despite the stigma associated with remaining unmarried, many unmarried females ‘overcome the pitfalls set by the norm of marriage and do attain womanhood’ (Sa’ar 2004: 2). Surely, given the diversity of human experience, it might make more sense to imagine that societies could conceive of a number of different ways to be an ‘adult’? In each case where anthropologists assert that marriage and children are the way to achieve ‘adulthood’, it therefore seems important to ask about unmarried or childless individuals and how, exactly, they are not thought to be ‘adult’. For, contrary to what we may assume for certain kinds of societies, marriage and the production of children may not be the only ways to live a fulfilled and valued life.

REFERENCES

Allman, J. 1996. ‘Rounding up spinsters: gender chaos and unmarried women in colonial Asante’, Journal of African History 37: 195-214.

Arensberg, C. M. 1937. The Irish countryman: an anthropological study, London: Macmillan.

Atkinson, J. M. 1990. ‘How gender makes a difference in Wana society’, in J.M. Atkinson and S. Errington (eds.), Power and difference: gender in island Southeast Asia, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bell, S. and E. J. Sobo (eds.). 2001. Celibacy, Culture and Society: The Anthropology of Sexual Abstinence, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bennett, J. M. and A. M. Froide. 1999. Singlewomen in the European past 1250-1800, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bloch, M. 1978. ‘Marriage amongst equals: an analysis of the marriage ceremony of the Merina of Madagascar’, Man 13(1): 21-33.

–––. 1993. ‘Zafimaniry birth and kinship theory’, Social Anthropology. The Joural of the European Association of Social Anthropologists 1: 119-32.

Boomgaard, P. 2003. ‘Bridewealth and birth control: low fertility in the Indonesian Archipelago, 1500-1900’, Population and Development Review 29(2): 197-214.

Bourdieu, P. 1962. ‘Célibat et condition paysanne’, Études Rurales (Paris) 5/6: 32-136.

–––. 2002. Le bal des célibataires: Crise de la société paysanne en Béarn, Paris: Points Seuil.

Cannell, F. 1999. Power and intimacy in the Christian Philippines, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carsten, J. 1997. The heat of the hearth: the process of kinship in a Malay fishing community, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Clark, G. 1994. Onions are my husband: survival and accumulation by West African market women, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cornell, L. L. 1984. ‘Why are there no spinsters in Japan?’, Journal of Family History 9: 326-39.

Dixon, R. B. 1971. ‘Explaining cross-cultural variations in age at marriage and proportions never marrying’, Population Studies 25: 215-33.

Dube, L. 1997. Women and kinship: comparative perspectives on gender in South and South-East Asia, Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

Forshee, J. 2001. Between the folds: stories of cloth, lives and travels from Sumba, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Franzen, T. 1996. Spinsters and lesbians: independent womanhood in the United States, New York: New York University Press.

Gennep, A. van. 1977 [1908]. The rites of passage, translated by M.B. Vizedom & G.L. Caffee, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Gibson, T. 1986. Sacrifice and sharing in the Philippine highlands: religion and society among the Buid of Mindoro, London: Athlone Press.

Goffman, E. 1971. Relations in public: microstudies of the public order, London: Allen Lane.

Goldman, N. 1993. ‘The perils of single life in contemporary Japan’, Journal of Marriage and the Family 55: 191-204.

Goody, J. 1976. Production and reproduction: A comparative study of the domestic domain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

–––. 1983. The development of the family and marriage in Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hajnal, J. 1965. ‘European marriage patterns in perspective’, in D.V. Glass & D.E.C. Eversley (eds.), Population in History: Essays in Historical Demography, London: Edward Arnold.

Harrell, S. 1986. ‘Men, women and ghosts in Taiwanese folk religion’, in C. W. Bynum, S. Harrell and P. Richman (eds.), Gender and religion: on the complexity of symbols, Boston: Beacon Press.

Hufton, O. 1984. ‘Women without men: widows and spinsters in Britain and France in the Eighteenth Century’, Journal of Family History 9: 355-76.

Jensen, R. and R. Thornton. 2003. ‘Early female marriage in the developing world’, Gender and Development 11(2): 9-19.

Jones, G. W. 1995. ‘Population and the family in Southeast Asia’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 26(1): 184-95.

–––. 1997. ‘The demise of universal marriage in East and South-East Asia’, in G.W. Jones et al. (eds.), The continuing demographic transition, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

de Jong, W. 2002. ‘Women’s networks in cloth production and exchange in Flores’, in J. Koning et al. (eds.), Women and households in Indonesia: cultural notions and social practices, Richmond: Curzon Press.

Krishnakumari, N.S. 1987. Status of single women in India; a study of spinsters, widows and divorcees, New Delhi: Uppal Publishing House.

Linn, R. 1996. ‘‘Thirty nothing’: What do counsellors know about mature single women who wish for a child and a family?’, International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 18: 69-84.

Mead, M. 1934. ‘The sex life of the unmarried adult in primitive society’, in I. S. Wile (ed.), The sex life of the unmarried adult: an inquiry into and an interpretation of current sex practices, New York: The Vanguard Press.

Ortner, S. B. 1981. ‘Gender and sexuality in hierarchical societies: the case of Polynesia and some comparative implications’, in S. B. Ortner and H. Whitehead (eds.), Sexual meanings: the cultural construction of gender and sexuality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parry, J. P. 2001. ‘Ankalu’s errant wife: sex, marriage and industry in contemporary Chhattisgarh’, Modern Asian Studies 35(4): 783-820.

Phillimore, P. 2001. ‘Private lives and public identities: an example of female celibacy in Northwest India’, in E. Sobo and S. Bell (eds.), Celibacy, Culture and Society: The Anthropology of Sexual Abstinence, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Reed-Danahay, D. 2005. Locating Bourdieu, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Rozario, S. 1986. ‘Marginality and the case of unmarried Christian women in a Bangladeshi village’, Contributions to Indian Sociology 20(2): 261-78.

Sa’ar, A. 2004. ‘Many ways of becoming a woman: the case of unmarried Israeli-Palestinian ‘girls’’, Ethnology 43(1): 1-18.

Scheper-Hughes, N. 2001. Saints, scholars and schizophrenics: mental illness in rural Ireland, Berkeley: University of California Press. Twentieth Anniversary Edition, Updated and Expanded, of 1977 original.

Sharpe, P. 1999. ‘Dealing with love: the ambiguous independence of the single woman in Early Modern England’, Gender & History 11(2): 209-32.

Smith, P. C. 1980. ‘Asian marriage patterns in transition’, Journal of Family History 5(1): 58-97.

Tan, J. E. 2002. ‘Living arrangements of never-married Thai women in a time of rapid social change’, Sojourn 17(1): 24-51.

Winnicott, D.W. 1958. ‘The capacity to be alone’, in The maturational processes and the facilitating environment: studies in the theory of emotional development, [1965] London: The Hogart

Please join our mailing list to receive notification of new issues