A well-disposed social anthropologist’s problems with the ‘cognitive science of religion’

James Laidlaw

[Editor’s note: this piece originally appeared in Harvey Whitehouse & James Laidlaw (eds.), Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science and is published in AOTC by kind permission of Carolina Academic Press.]

What is true is that each action is explained, in the first place, by an individual’s psychology; what is not true is that the individual’s psychology is entirely explained by psychology. There are human sciences other than psychology, and there is not the slightest reason to suppose that one can understand humanity without them (Williams 1995: 86).

Since what follows will be critical of some aspects of the foregoing papers, and since it will argue that what its proponents call ‘the cognitive science of religion’ will not be able to fulfil some of their hopes and ambitions, at least in the form in which they are currently held, it might be helpful if I begin by making clear that I am not unsympathetic to the enterprise.[1] I do not share with some of my fellow anthropologists any hostility to what they disparagingly call ‘Western’ science (or more specifically to biology, genetics, Darwinian evolutionary theory, or experimental cognitive psychology). I have no objection to the notion of human nature or to the thought that the cognitive architecture of the brain materially affects the ways in which humans learn, think, and behave. Further, it seems to me clear that developments in cognitive science in recent decades have included ideas and discoveries that are of real interest and consequence for social anthropology in general and the study of religion in particular.

However, in order that the most might be made of these advances, it is important that their extent not be exaggerated, and that the character of their interest and consequence not be mistaken. Some at least of the contributors to this volume clearly expect a complete revolution in the anthropology of religion and, in particular, the comprehensive superseding or encompassment of hermeneutic or interpretive by what they call scientific methods. I am sure that these expectations will be disappointed. There are aspects of religion for which cognitive science has begun to provide a persuasive explanatory account, and undoubtedly there is scope for further progress along similar lines. However, I shall argue that what this tells us about is only a very little of what we call religion, and that this limitation derives from the very nature of the cognitive-science enterprise. The idea that we are seeing the beginnings of a new discipline that could provide what hopeful protagonists call a ‘complete explanation’ of religion, even if it is imagined that others such as interpretive anthropologists might still have a role in the enterprise, is I think not well founded. I do not think that any such enterprise is in prospect, and if or to the extent that it were to be, cognitive science could not provide the conceptual basis for it. The claims I shall make are as follows:

- Cognitive science, like any explanatory method, has blind spots as well as foci.

- Explanation is intentional, so necessarily plural, and causal explanations in terms of mechanisms of cognitive processing cannot substitute for the contextual interpretation of thought and action, yet the ambition of an integrated ‘cognitive science of religion’ ignores this irreducible plurality.

- While cognitive science can provide a causal account of some religious phenomena, this is not, as its practitioners claim, an explanation of ‘religion’; because

- much that is distinctive about religious traditions as traditions falls outside the definition of religion used by cognitive scientists; and in any case

- religion is not an object, such that ‘it’ can be defined analytically rather than historically, and therefore is not a proper object for the kind of explanations cognitive science can provide.

- What cognitive science can and to some extent has developed explanations for is what the Enlightenment called Natural Religion, and what both it and many religious authorities have called Superstition.

- This being the case, the contribution cognitive science can make to any general understanding of religion or to the study of particular religious traditions is necessarily ancillary, and roughly equivalent to the contribution that technical knowledge about materials can make to aesthetics and the history of art.

- The anti-humanist methodological exclusions on which cognitive science is founded are reflected in the way some if not all cognitive scientists of religion handle the concept of belief, which, even where this might be against their best intentions, involves implicit denial of the reality of human reason, imagination, and will.

1. The necessary partiality of cognitive science

Reviewing the range of possible explanations for religious concepts, Pascal Boyer (2002: 69), arguing for the value of the cognitive-science approach, observes that if we seek to explain the reason why people have a concept, we often assume that it must be, precisely, a reason; that is, a set of facts that make sense of the concept’s import.

When we say, ‘People worry about the ancestors’ reactions because [they believe] the ancestors are powerful,’ we put these two facts together (a worry about ancestors, a belief in their power) because one seems to make sense in the context of the other.

But, he rightly observes,

we must remember that many aspects of cognitive processing are explained by causes rather than reasons, that is, by functional processes that do not always make sense. We all have a very good memory for faces and a much poorer one for names. There is an explanation for that. But it is not that it makes more sense to recall faces than names. It is just the way human memory works.

This is a telling point, and it identifies most economically the description under which cognitive science understands human thought and conduct: it does so as and insofar as they are the subject of causes, as distinct from reasons. It is just insofar as thought can be conceived under the causal description – as the outcome of mechanisms of information processing – that cognitive science can comprehend it. But Boyer, in making his point, implicitly concedes that contrariwise there are aspects of our thinking that are explained by the reasons agents hold rather than the causes that affect them.[2] And these, by definition, cannot be part of a cognitive-science approach.

Before I go any further, let me be clear: I am not criticising cognitive science on the grounds that it makes this exclusion. Any research programme must be founded on conceiving its subject matter in a certain way. This will always involve exclusions. You cannot focus equally on everything at once, or you would not be focusing at all. The point is to understand the consequences of the decisions you make.

Although of course cognitive science and scientists come in a variety of forms, certain decisions are constitutive of the approach as such. The crucial decisions are the commitment to regarding thought as information processing and therefore to regarding humans (like other animals) as, in this respect, like certain machines.[3] One can concede the productivity of this point of view, while observing that it excludes much. It excludes, significantly for my purposes here, everything that humans think and do in the reflective exercise of the kinds of capacities I shall designate, in shorthand here, as reason, imagination, and will. To the extent that humans are possessed of such capacities – the extent itself is debatable (as of course is their correct delineation) and I will simply be assuming that it is not negligible – their conduct will be inexplicable as the result of causal mechanisms of this kind. It will be inexplicable, to adapt the point from Boyer, except (also) in relation to reasons.

It is worth observing here – we shall return to the point later – that one of the things that the word ‘religion’ identifies is the media in which mankind has as it happens made many of its most sustained and concentrated attempts to exercise its reason, imagination, and will. The point that cognitive science therefore works, insofar as it does, by a methodological exclusion of much that we mean by religion, will be relevant to assessing the scope and likely prospects of the ‘cognitive science of religion’.

The case here is comparable to the exclusion on which neo-classical economics is constituted. No one can doubt that economics, not least in its formal and more-or-less mathematical sub-disciplines, has developed, as cognitive science aims to do, a sophisticated body of theory founded on scientific method and assumptions. This is a body of theory that issues in precise, quantified, testable predictions. But as John Stuart Mill observed at the very foundation of the discipline in this form, there is a cost. Political Economy, he observed,

does not treat of the whole of man’s nature as modified by the social state, nor of the whole conduct of man in society. It is concerned with him solely as a being who desires to possess wealth, and who is capable of judging of the comparative efficacy of means for obtaining that end. It predicts only such of the phenomena of the social state as take place in consequence of the pursuit of wealth. It makes entire abstraction of every other human passion or motive (1864: 137).

This ‘entire abstraction’ is productive, so long as it does not lead its practitioners to suppose that ‘every other human passion or motive’ is on that account actually either absent or trivial in human affairs. But it is an easy over-extension of enthusiasm for a powerful method or technique to want to insist that only problems that it can be used to solve are real or well-formed problems. And some economists have indeed regarded human conduct as really being motivated by the single passion or motive their method can comprehend. These days, most economists probably recognise that their methods can throw light on only certain aspects of human conduct, and those too viewed from a certain point of view. But a range of reductive and imperialist ‘economic theories’ of human behaviour as such, or of love or law or war or religion or whatever, continue to be put forward in more or less popularising forms.

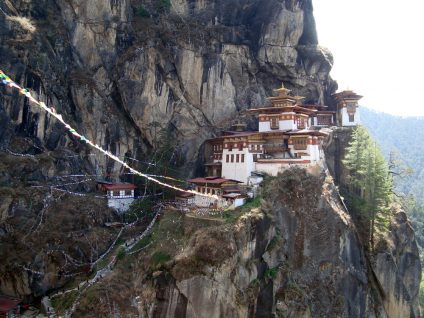

Taktang Palphug Monastery, Paro, Bhutan (photograph by the author)

In cognitive science too, some practitioners and enthusiasts in various ways both explicitly and implicitly deny the consequences of the exclusions on which their discipline is founded. So several authors, including some contributors to this volume, express the hope or expectation that hermeneutic or humanistic methods in the study of religion will, progressively, be reduced in scope or even replaced as a natural consequence of the advance of cognitive science.[4] On this view, rival explanatory paradigms are conceived as being in a zero-sum game where to win would be to stand in sole possession of a single field, having successfully either excluded or ‘reduced’ one’s opponents. Others, more liberally, imagine interpretive methods surviving, but only insofar as they are ‘integrated’ with cognitive-scientific approaches (see for instance Lanman 2007 and Whitehouse 2007). Now two things might be meant here. One is that an interpretation should not logically contradict the conclusions of scientific research. That is unexceptionable, and could provide the basis for ongoing peaceful and distinct coexistence between humanistic and cognitive-science approaches. But often more is meant, namely the claims that the conclusions of cognitive and interpretive research will become substantively integrated, that such integration is indeed a criterion for the validity and rigour of the latter (evidence that it is not merely fanciful[5]), and that therefore ultimately they will merge into a single body of knowledge, which body of knowledge it will make sense to call, because the cognitive method is what will stand at its centre and give it shape, the ‘cognitive science of religion’. The spirit of the proposal need not be hostile – I happen to know that in some cases it is genuinely open – but the stance is not compatible with acknowledging the limitations and blind-spots that follow, naturally and inescapably, from the exclusions on which the method is based. Humanist and interpretive approaches to human thought and conduct do not make the same exclusions (they make others, of course). Yet the criterion of integration presupposes that scientific and humanist approaches are fundamentally the same enterprise, on the apparently reasonable grounds that they both seek to explain the same thing, namely religion. But this apparently reasonable supposition is, I want to insist, mistaken. Neither is it the case that the ‘religion’ they could conceivably give an account of is in fact the same thing, nor is it the case that what it would be for them to succeed in explaining ‘it’ is the same thing.

2. The intentionality, and therefore plurality, of explanation

First, let me address the question of the meaning of explanation. The hopes and expectations entertained by many in the cognitive science of religion of either the replacement of interpretive by cognitive-science accounts or their integration into a single scientific method only make sense if it is forgotten that explanation is interest-relative, and therefore a necessarily plural and heterogeneous category.

To use one of Hilary Putnam’s classic examples (1978: 42-3), it is unassailably true, but hopeless, to explain Professor’s X’s presence, naked at midnight in the girls’ dormitory, by saying that (a) he was naked in the girls’ dormitory at midnight -ε, so that he could not exit the dormitory before midnight without exceeding the speed of light, and that (b – covering law) nothing (certainly not professors) can travel faster than light. This is hopeless as an explanation because although true, it is irrelevant to the interest we have in asking the question. It does correctly answer a question, but not as it happens one that anyone has asked.

A why-question always presupposes and is motivated by a definite range of interests (in this case obviously we are interested in motives and intentions). An explanation is never simply and completely an explanation of any thing (or event, or process, or state of affairs, or series, etc.); it is an explanation of that thing from a certain point of view, in answer to a certain kind of question. We may approach the same phenomenon with more than one interest. Different explanations ‘of the same thing’ therefore might equally be valid, and not in competition, because they are answers to different questions with respect to ‘it’. So, to use another of Putnam’s examples, the bank robber Willie Sutton’s famous reply when asked ‘Why do you rob banks?’ – ‘That’s where the money is’ – was a good explanation, and an answer to the question he had been asked, if we imagine his interlocutor to have been another crook, but it is not an explanation at all, and not an answer to the question, if we imagine the question to have been asked, as it were, by a priest.

So explanation is intentional. Whether and to what extent any account of a set of phenomena is explanatory depends in part on to whom it is addressed. This means that the idea of a complete explanation of a phenomenon is an incoherent one. How comprehensive or satisfactory an explanation is, is never entirely a matter of the phenomenon to be explained, but always also depends on the questions and interests the enquiry is answering. The point of Putnam’s examples, and of my citing them, is not to show that one kind of explanation (in terms of reasons and motives) is better than another (reductive or causal), any more than the reverse, but just to show that they really are different, and that there are circumstances in which one cannot substitute for the other, however rigorous it might be.

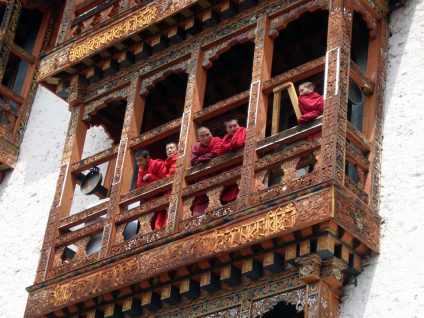

Monks at Tamshing Goemba (photograph by the author)

Because cognitive science places human thought under the category of material cause, its why-questions are always roughly equivalent to asking of any incidence or pattern of representations or practices, ‘through which mechanisms’, or ‘impelled by which forces’, or ‘under what selective pressure’ did they arise? As Boyer rightly observes, causes of these kinds are quite independent of whether it makes any sense for anyone to hold these representations or engage in these practices rather than any others. By contrast a humanistic study that took reason, imagination, and will seriously as constitutive of its subject matter would ask why-questions whose natural paraphrases would be quite different. Many, for instance, would be teleological. They would concern the ideals and values towards which the ideas or practices concerned are orientated. To recognise thought as exercise of reason, for instance, would be to acknowledge that it aims at truth, and would be to evaluate it accordingly. To ask for an explanation of religious thought and practice under these two sets of descriptions is therefore to ask quite distinct sets of questions. Now the answers to one might well be of interest or help to someone seeking answers to the other, and actual contradiction will not be possible between true answers to any of them. I shall return below to the question of what the proper relation between causal and interpretive accounts of religious life might be. For the moment, it suffices to say that there is no reason whatsoever to expect that the answers will ever be the same in substance, or that being in possession of answers to one set will obviate the interests that motivate the other.[6]

This is true in general terms of the humanistic and historical understanding of human affairs on the one hand and reductive or naturalistic understanding of human behaviour on the other. It is however especially vividly true of these two modes of experience and understanding, as applied to the phenomena we call religion. I said above that religion as conceived by cognitive science is not the same thing as that conceived by humane study, and I turn now to the reasons why this must be so.

3. Explaining some widespread religious beliefs and practices

The social and cultural anthropology of religion has for many decades overwhelmingly emphasised the diversity of religious beliefs and practices: diversity as between peoples and places and religions and, for the historical and literate ‘world religions’, as between official doctrines and the local variants within those traditions. It has been a bold move by the proponents of the cognitive science of religion (though one of course that was anticipated by Marxists and others) to insist that the supernatural beings and entities who populate the popular religious imagination right across the globe are in fact substantially similar, and then to offer a distinctive and persuasive explanation for why this should be so (Boyer 1994, 2001, Guthrie 1993). Similarly, they have argued that beneath the detailed variety of forms of religious ritual, there are a few basic types generated by reasonably simple and very general cognitive principles governing actions and interactions relating to these supernatural beings (Lawson & McCauley 1990; McCauley & Lawson 2002) and/or responses to the felt risk of danger in dealing with them (Boyer 2001; Boyer & Lienard in press). A further theme that has been developed with some success is to explore the ways in which the capacities and limitations of the mechanisms of human memory differentially constrain or enable the retention and transmission of different mental representations, so that some ideas are intrinsically very difficult for human minds to acquire and retain while others are much more easy and therefore are extremely widespread (Sperber 1985, 1996; Whitehouse 2000, 2004; see also Whitehouse & Laidlaw 2004).

The phenomena under discussion here are, it is convincingly claimed, so widespread in human populations because their causes – evolved mechanisms of cognitive architecture – are universal to humans. Thus they are to be seen, albeit in locally variable forms, everywhere. But if they are indeed very widely distributed across societies, and of incontestable importance, they do not come near to constituting all that we might reasonably call religion. This fact is partly disguised by, and possibly also from, practitioners of the cognitive science of religion by the virtually unanimous agreement among them in defining religion as beliefs and practices relating to spiritual or supernatural beings.

At first sight, to most anthropologists, this insistence on defining religion with reference to supernatural beings seems like a curious, merely anachronistic reversion to the Tylorian ‘intellectualist’ theories of the origin of religion from the end of the nineteenth century. Durkheim famously attacked definitions of that kind (1995 [1912]), Evans-Pritchard buried them (1965), and no one much has thought it worthwhile trying to resurrect them since.[7] But the matter is far from trivial. Durkheim’s refutation turned crucially on Buddhism, which, as he rightly said, is not centrally concerned with deities at all. Guthrie (2007) and others (Lawson & McCauley 1990; Boyer 1994, 2001) have replied by observing that throughout the Buddhist world popular devotional practice prominently features deities of various kinds. This is quite true. Propitiation of deities is indeed common, but no remotely reflective Buddhist, including those who spend time and resources participating in such rites, would confuse them for a moment with following the teachings of the Buddha. And whatever else Buddhism is, it surely must include that. Buddhists will certainly maintain so.

Doors at Jampey Llakhang, Chokhor valley, Bumthang (photograph by the author)

Now, to what do we apply the term religion in this situation? At one level, it does not matter. Anthropologists for generations have happily applied it both to the transmitted teachings of the Buddha and to Buddhists’ beliefs and practices relating to gods and spirits. Some have indeed seen it as their calling to demonstrate that in any given local social context they form a single integrated complex whole (Leach 1968, Tambiah 1970).[8] But this has been of no serious consequence precisely because for these authors and for the interpretive enterprise they are engaged in the question of what counts as religion is of absolutely no theoretical importance. There is no such entity they have sought in any sense to explain. These authors’ interpretive and functional holism embraces equally a good deal that no one would ever be seriously tempted to call religion. In these circumstances, no real definitional question arises with respect to religion.

But this is not true for the self-declared cognitive science of religion. For this project, the definition of its subject matter is of considerable theoretical moment. Consider Guthrie’s contribution to this volume (2007). Although he begins by accepting, apparently, that the category religion is vague and has no indigenous equivalent in many societies, he nevertheless seeks an explanatory ‘theory of religion’. So the question of what is and is not included in the explanandum is a recurring concern. He proceeds on the operating assumption that theories of religion are adequate if and only if they apply comprehensively and exclusively to ‘it’. So, for instance, what he calls ‘comfort theories’ are rejected on the grounds that there are instances of ‘religion’ to which they do not apply. In Guthrie’s own terms, this is indeed the correct way to proceed. A series of important questions about the evaluation of his own theory – its testability, its completeness, and the adequacy of his treatment of apparent counter-evidence – all depend on him being fastidious in just this way. I am not claiming that it is a fault in Guthrie that he seeks to define his object of study in this manner. On the contrary, it is a virtue. It is a problem, because it is a source of real potential confusion, only that he wants that object to be defined as ‘religion’.

4. Religious traditions as traditions

Let me begin to illustrate why it is a serious problem by describing the traditions of Jainism and Theravada Buddhism. I choose these examples partly because I happen to know a certain amount about them, and partly because the features of them that elude a cognitive-science characterisation of religion are so prominent and clear.[9] But the general point applies in fact to all religions insofar as they are historical phenomena, which of course includes religions (such as those of so-called ‘tribal’ peoples) whose history has not (until recently) been written down.

Both Jainism and Theravada Buddhism are soteriologies, traditions that transmit and embody a distinctive project of self-fashioning, in pursuit of an ideal of liberation from embodied existence. These projects are systematically pursued only by ordained renouncers, who have never been more than a minority of the followers of these traditions. But the ways of life of their much more numerous lay followers have nevertheless been inflected by their renunciatory projects. Both projects took definite form at the same place and time (the Gangetic plain in eastern north India in the 5th to 4th centuries BC). In both cases they incorporate ideas, practices, and forms of organisation that were part of the general cultural milieu of that place and time, including a sombre view of every-day householder existence and an ideal of enlightened liberation from it, an abstractly formulated moral theory relating directly to the psychophysical individual, and forms of organisation for single-sex groups of religious professionals among which there were traditions of experimentation with practices – meditation, changes in diet, other forms of austerity – designed to effect psychological changes. But equally, in both cases, specific known individuals (Mahavir Swami and Gautam Buddha respectively) gave their respective projects qualities and a style which each still retains, though both have changed radically in various ways, through histories of schism, political patronage and persecution, encounter and competition with other traditions, changes in the composition and fortunes of their followers, and movements of self-conscious reform. The two traditions continue to bear the recognisable stamp of the thought and imagination of Mahavir and the Buddha respectively, and the distinctive ideas, concerns, practices, and institutions they bequeathed, and this makes them unmistakably distinctive forms of life. This continuity is not to be accounted for in terms of there being simply consistent and continuous transmission of shared beliefs, but rather by what Carrithers calls a ‘patterned flow of contingencies and aspirations, routines and imaginative responses’ (Carrithers 1990: 141). As important to the transmission and content of the traditions as beliefs, are institutions, roles and relationships, practices (including and especially bodily techniques), narratives, and material culture including visual representations.

In these traditions, deities, ghosts, spirits, and magic are all part of the picture. As cognitive science would predict, renouncers and lay followers alike, along with the rest of the species, ‘catch’ these ‘minimally counter-intuitive’ or ‘cognitively optimal’ representations. But they are not what these projects are about, nor are they in any sense central or even, frankly, relevant to them. It would be highly eccentric not to call these traditions ‘religion’, if one is going to use the term analytically at all, but as practitioners will tell you, ‘gods have nothing to do with it’.[10] So although if you look at life in a Jain or Buddhist community you will find ‘religion’ as cognitive science expects to find it – they are valid instances of the patterns it seeks to explain – this will all be at best peripheral to an understanding of these traditions as traditions. That is, cognitive science will tell us as much or as little about what Jains and Buddhists believe and why as it will of anyone else, but nothing at all about what they believe or do, distinctively, as Jains or Buddhists. To capture the sense in which these traditions are religious traditions, you would need at the very least to allow some aspects of a wholly different order from beliefs in the existence of gods and ghosts into your characterisation of religion. There are several ways one might sensibly go about this, but I hope it will be immediately apparent, for instance, how much more to the purpose is Jenkins’ suggestion ‘that religion be best understood as the expression of the desire to be human in a particular form’ and therefore that religious traditions are different socially embodied conceptions of human flourishing (Jenkins 1999: 13).

This is why religious traditions centrally and constitutively include concepts that may have nothing necessarily to do with belief in supernatural beings, and of which cognitive science will find it extremely difficult to give any meaningful account. I mean concepts, such as shame or compassion or penitence – or, in the Jain case, vairagya which translates roughly as ‘disgust (with the world)’ – that refer to what it is to be a human subject, because they only have meaning in relation to webs of other such complex psychological terms. Shame makes no sense without related notions, typically such as respect, tact, shyness, and reserve (not necessarily honour; see Wikan 1984). And because they are also inherently and strongly evaluative – judgements of worth are intrinsic to the meaning of these concepts and the judgements include second-order and self-reflective valuing of values and so on – they can only properly be predicates of a moral subject (Frankfurt 1988). As Williams (1995: 82) puts the point, the qualities described by such concepts,

can be possessed only by a creature that has a life, where this implies, among other things, that its experience has a meaning for it and that features of its environment display salience, relevance, and so on, particularly in the light of what it sees as valuable.

Not all such concepts are overtly ‘religious’. But one of the things religious traditions do is to propose whole webs of these strongly evaluative concepts.

If one thing religious traditions do is to propose strongly evaluative psychological concepts, another is to embody practices through which the qualities they describe are variously cultivated, elicited, and enforced. The reflective process of understanding and articulating one’s experience in terms of these emotions, motivations, and qualities of character is never just to describe but always also to evaluate, and thus to affect. In understanding and articulating our experience in such terms, we necessarily act upon the self, because we ascribe not only content but import to the emotions or motivations or qualities of character so described. Such self-interpretations are constitutive (Taylor 1985: 45-76). That is to say, while we may in important ways be mistaken about our own thoughts, emotions, and motivations, our self-understandings are never merely mistakes, for they are part of the fact of the matter, part of what they seek to articulate. The articulation, even if partly mistaken or even actively self-deluding, is nevertheless part of its object. But further, it is important not to think of this constitutive self-interpretation as a merely psychological process, in the sense of it being internal to the individual. It takes place within institutions and relationships, and through instituted practices and language, and this is why although the claims I have made in this and the preceding paragraphs are unashamedly general claims about what human social life is like, and therefore about ‘human nature’, the precise forms in which human subjects are reflectively constituted are on this view historically variable.[11]

Jampey Llakhang, Chokhor valley, Bumthang (photograph by the author)

Each religious tradition has its own distinctive ways of describing, judging, and shaping character in relation to its historically created and developing conceptions of human wellbeing and worth. It is through instituted religious practices – forms of worship, confession, penance, celebration, interaction, ecstasy, and so on – that people come to have the emotions and self-understandings that make them Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Jain, or whatever. And just as it is not possible to be a Jain, or to feel ‘disgust (with the world)’, without the language needed to form this self-interpretation, so the language and the emotion could not exist without the tradition and the institutions and practices through which it is cultivated and experienced. And because these emotions and motivations are historical products, invented and developed contingently in particular times and places, and sustained by particular practices and institutions, they cannot be adequately described purely in terms of cognitive mechanisms, internal to individual minds. They are particularly clear and strong examples of those aspects of language, meaning, and therefore thought and experience that are inter-subjective, which is to say ‘not (only) in the head’ (on which see Putnam 1975 and especially Pettit & McDowell 1986). Again, ‘religious’ traditions are not the only kind of contexts in which all this occurs, but overwhelmingly the most concentrated, sustained, influential, and enduring patterned ways in which humans have done this have been religious traditions. This is true, to repeat, of religious traditions as historical phenomena irrespective of whether or of the extent to which they are literate traditions. In the case of Jainism and Buddhism, moreover, it is very overtly and self-consciously what these traditions are about.

5. From analytical to historical characterisation of religion

Now, my purpose in setting out this aspect of the meaning of ‘religion’ is not to propose it as the basis for a definition, either to replace or even to complete those that focus on beliefs and practices relating to supernatural beings. Many have laboured, including many cognitive scientists, to develop a defensible analytical definition of religion (see for instance, and in many ways admirably, Saler 2000). While many brilliant and illuminating points have been made in the course of these discussions, the effort is misguided. It is not just malign accident that ‘religion’ in modern English has these (and other) disparate meanings. The word has a history that is inseparable from the fact that the phenomena it describes are historically constituted and variable. This history is a complex one, and there is neither reason nor space (nor am I competent) to try to tell it all here.[12] In any case neither telling it, nor any definitional fiat, can wish that history away. The most important point is that ‘religion’ as it is understood in the modern (post-) Christian West is not an object with a single origin, let alone a single essence that defines it, but a fairly local and contingent meeting up of several different questions and areas of concern. Seventeenth-century England was a crucial turning point for reasons that are lucidly summarised by Jenkins,

In a period prior to the seventeenth century, theology had to do with everything, considered in the light of God’s saving action and purposes, and the word ‘religion’ was a relatively unimportant term, concerning the right ordering of worship. In the seventeenth century, a mutation took place, whereby notions of cause and effect became important. ‘God’ then became the name for the final cause of everything, and ‘religion’ became what concerns God, that is, separated from the spheres of specific causalities in the world – the public sphere, politics, economics and so forth. This constituted a real reduction, since one can in fact do without a universal cause; ‘religion’ in this reduced sense was born to be irrelevant (Jenkins 1999: 9).

Every member of a modern, post-Enlightenment society is in some measure obliged to have beliefs about politics, economics, public morals, and science, and in these spheres is obliged further to have beliefs that they themselves believe, at least, are rationally grounded. Religion, by contrast, has become optional, a matter of personal subjective need – for meaning, comfort, identity, and so on. Before this transformation, as Asad in particular brings out (1993: 27-54), processes of shaping character and authorising judgements of truth and worth were much more prominent in the self-understanding of Christianity than they have become subsequently. It would not have been necessary or made so much sense then, as I have done here, to invoke Jainism and Buddhism in order to highlight their importance, relative to matters of internal mental state such as ‘belief’ or ‘faith’. Although ‘belief’ has always been central to Christianity in ways that mark it out from other traditions (Ruel 1982), nevertheless the transformation in the sense of this, from public affirmation to internal state of mind, is distinctively modern, and it is anachronistic if simply applied elsewhere.[13] It is not so much that such a definition is wrong; it is rather that it is historically and ethnographically insensitive to regard it or any variation of it as the definition of a simply existing entity. There is no such entity to define.

Tango Goemba, north of Thimphu (photograph by the author)

This means that the effort to discover what religion really is – to get the definition of it definitively right – is based on a category error. The changing history of how the word ‘religion’ has been understood is, inseparably, the history of ‘it’ changing. By contrast the word ‘gold’ also has a history, and it was used and had meaning before the subatomic composition of gold was discovered. But neither that discovery, nor any other change in human understanding or use or valuation of gold, had any effect on what gold is as a material substance. It is not in this sense an historical phenomenon, and this makes a difference to the kind of knowledge that can be hoped for of it. So a chemist can validly formulate theories and generalisations about gold, as it always has and always will be, and insist that it just is different from iron pyrites, whatever anyone has ever thought or done, mistaking one for the other. The history of human interactions with gold is neither here nor there. And just as it would be an error for an historian or social scientist not to acknowledge this, and not to respect the consequent limits to the applicability of his or her methods to genuinely natural facts (for an example of such error, see Latour 1998), so it is an error not to acknowledge and attend to the intrinsically historical character of religion.[14]

6. Rediscovering natural religion and explaining superstition

So the focus on supernatural beings, the focus on belief, and the fact that it is not historical all weaken cognitive science’s definition of religion. Jenkins points out that the transformation from pre-Enlightenment theology to the post-Enlightenment disciplines of the ‘study of religion’ was built upon a reduction, from knowledge about everything, seen in a certain light (in the light, that is, of the most important facts there were), to a certain distinct subject matter. This reduction is a prerequisite for the modern idea of there being different ‘religions’, each a token of the general type (‘religion’), where each is a different, logically equivalent set of beliefs, held by different people and/or in different times and places, about that same subject matter. The cognitive-science definition of religion presupposes just this transformation. It defines religion as sets of representations, and/or practices ‘relating to’ those representations, each with the same general kind of content. Once you have the idea of each ‘religion’ as a species of a genus or a token of a type, you have by implication the question of how much they share and the idea of the basic form of which they are all a variant. This was the problem constituted in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as that of ‘Natural Religion’: what did human reason, or human nature, require or incline man to believe? (Harrison 1990: 28-34).

It is not surprising that cognitive science has rediscovered basically this problem. It asks, first: what, given its architecture and mode of operation, is the human mind, as a cognitive processing device, disposed to believe?

That is to describe the subject matter of cognitive science from more or less within its own terms of reference, but there is another way to put the same thing, and I think this is worth spelling out, although it may not please either the cognitive scientists or (though for different reasons) many social and cultural anthropologists. This is to say that, as viewed from within some, perhaps even all, self-conscious religious traditions, what the cognitive science of religion gives us is an account of ‘superstition’: not the self-conscious products of reason, imagination, and will, not what the tradition is to itself, but rather the popular beliefs and practices which in particular the untutored and uncultivated are always prone to, which are at best incidental to a good, or pious, or virtuous, or enlightened life, and at worst highly destructive illusions or temptations. One of the reasons it is worth drawing attention to this coincidence of object is that cognitive science agrees at least with this: that the ‘religion’ it identifies and explains is built up from a series of observable mistakes: beliefs we can be shown to acquire not because the world is thus and so, but because our cognitive programming mechanisms pre-judge the matter and bias our perceptions. And, specifically of religion, cognitive science asks: which of the apparently infinitely many possible erroneous things of a certain kind (those in which supernatural beings or processes figure) is the human mind most disposed to believe?

This then is why supernatural, or as cognitive scientists often say ‘non-empirical’ beings, are essential to its definition of religion: the fact that these entities, though non-existent, nevertheless present themselves to human minds is an index of the extent to which the structure of the mind, rather than the content of the world, determines the representations humans come to have, and therefore of the extent to which the explanation of these beliefs and the associated behaviour must be in cognitive terms. If gods were admitted to exist, the role for cognitive science in explaining why we believe in them would of course seem less compelling. If such beings are what religion is defined as being about, the compelling relevance of the approach appears to apply to all of it. The oft-cited distinction between a cognitive mechanism’s ‘proper’ and ‘actual’ domain recasts this thought in terms of evolutionary psychology (Millikan 1984, Sperber 1997). It is not even, in evolutionary terms, useful that we have these representations. They are errors produced as by-products by mechanisms we have because those mechanisms were useful for other reasons – thus for instance our tendency to identify agents became hyperactive when we were Neolithic hunters (thus Barrett 2007, Guthrie 2007, and Cohen 2007). It is partly because error is thus intrinsic to the cognitive-science identification and definition of religion that it coincides, in its understanding of its subject matter, with the religious category of superstition.

It is not to denigrate what the cognitive scientists have been doing to point this out. They have given us a new description of some general phenomena and a new explanation for them, one that includes an account of why the beliefs in question are so resistant to suppression and found among people who are not otherwise or in the more usual sense ‘religious’. By this account, convinced atheists are no more able than the devout to resist ‘catching’ superstitious ideas, for we are all by nature highly susceptible to them. This brings out another more general point: for cognitive science, people are routinely mistaken about their own beliefs. Their thinking is guided, as Boyer insists, by causes (of which they are generally unaware) rather than any reasons they may consciously hold. And, to repeat, this is why, insofar as human thought is in fact guided by reflective reason, cognitive science has nothing to say about it. And this in turn is why cognitive science, while it can frame interesting hypotheses about cross-culturally recurrent tendencies, has been and will remain unable directly to explain any of the distinctive features of any specific religious tradition.

7. The proper study of cognitive science

We have seen why it makes sense to define the object of a cognitive science’s inquiry with reference to belief in supernatural beings. For a generalizing science, popular religious-superstitious beliefs may be a satisfactory object of enquiry, and there can be no objection to those who wish to do so pursuing that inquiry. And no harm will be done in calling this enterprise the ‘cognitive science of religion’ so long as it is recognised that this is only a very constricted, indeed one must say an impoverished, idea of ‘religion’. It excludes the history of religion as mankind’s various more concentrated and sustained attempts to think and act out its conceptions of human value and worth, and the particular and varied achievements and follies that have resulted. Nothing cognitive science has any prospect of achieving will obviate the need to understand these, in humanistic terms.

My argument is not that actual religions are complex and scientific explanations must simplify. The right kind of simplification is generally a necessary part of explanation, whether scientific or otherwise. The point is rather that no single kind of simplification is in this sense right for any and every kind of question or interest. Similarly, the argument is not that cognitive science cannot take contingently variable circumstances into account in formulating its generalisations. Nothing prevents this. What it cannot do, using its methods, is actually to account for the contingent historical creations of reason, imagination, and will. The attempt to use the methods of cognitive science to explain particular forms of religious life is in effect to deny that this is what they are.

Quite properly, since cognitive science generally seeks explanation of recurrent features of thought in terms of universal causal factors, its data are generally understood and enumerated as instances of the regularities they reveal. Its facts are statistical facts. To understand religious traditions as traditions is necessarily a qualitatively different exercise. For this, it matters that some things could happen only after specific other things, and some of them happened only once. Because and insofar as the phenomena we seek to understand are conceived as the products of human reason, imagination, and will, this exercise calls for the understanding of events, actions, beliefs, and practices not as instances of a regularity or as items in a series, but as meaningful contingencies, and it therefore understands them by means of contextualisation. To try to answer one of these two kinds of question, or to account for phenomena presented by one mode of understanding, using concepts, methods, and reasoning drawn from the other, is to be strictly irrelevant.[15]

Humanistic study, as pursued alike by history and anthropology, cannot ignore the fact that in religion people have aimed at certain values and virtues, including and especially truth. To study the way they have variously invented, discovered, criticised, amended, defended, and reformed the doctrines, practices, and institutions of their religion, and have tried, succeeded, and failed to live up to and according to them, is necessarily at least in part to ask whether and to what extent, in doing so, they have realised their values and ideals.[16] To seek instead to explain their beliefs and behaviour causally as the outcome of the mechanics of information processing, and largely with reference to processing errors, is just not to look them in the eye.[17] This is no way to achieve ‘integration’ of interpretive and scientific-explanatory accounts. In any case, the situation I have described calls not for integration but for a somewhat different kind of peaceful coexistence.

The difference between scientific and humanistic understanding is not in itself or most importantly a difference in subject matter – the same events can figure in both – so much as it is a difference in the description under which subject matter is conceived, experienced, and understood. But this does mean that the objects of study in a humanistic study – socio-historically embodied religious traditions – are simply not instances or cases of the entity that the cognitive science of religion seeks to understand. One can better think of the latter as a substrate, which, if and insofar as cognitive science has established its case, we may regard as always present and part of the raw material from which self-conscious traditions – products of reason, imagination, and will – are fashioned. This is not to say that the cognitive science of religion cannot inform humane study of religious traditions.[18] Knowing about the ‘substrate’, the medium with which reason, imagination, and will are constrained to work, can undoubtedly be enlightening: but only in limited ways. It can explain why there are commonalities, but cannot provide a complete or satisfying account of any particular practice, belief, or institution in any particular time and place. Indeed, insofar as a practice, belief, or institution is indeed particular, it can have nothing relevant to say about it. It can no more form the basis of an account of any of the distinctive, historically embedded projects of human flourishing than a detailed study of metallurgy would constitute an adequate response to Donatello’s David.

Now that comparison, I am aware, will sound highly evaluative. Am I saying that self-conscious products of reason and moral aspiration are nobler and more valuable than the unconscious reflexes we exhibit as by-products of the evolved architecture of our brains; that conscious and reflective thought and practice is more of a human achievement than the (mostly false) beliefs we can scarcely avoid or escape? Well, although it is quite incidental to my argument, I am happy to admit that I do indeed think this. Nothing follows from this analogy, of course, about the worth or difficulty of the respective disciplines that study these phenomena. Some things do follow, however, about the proper relations between them. Materials science is a serious and demanding science, and a good historian of sculpture will be well advised to acquaint him or herself with many of its findings, and to be open to the fact that insights will be gained into particular historical events or processes by doing so. At all times, the capacities and limitations of available materials will influence what sculptors have done; at some times, the availability of new materials or innovations with familiar ones will radically have affected what was possible; and fully understanding the achievements of the very greatest sculptors will often depend on being able to appreciate the technical mastery that informed their genius. For these reasons a whole host of facts uncovered by materials science might be relevant to the art historian. Some interpretations an art historian might otherwise wish to put forward could be ruled out, or shown to be trivial, by such facts; others might be suggested. But none of this makes the questions or the methods of material science the appropriate ones around which to organise a study of Renaissance sculpture. And so it is with cognitive science and religion.

Methods and concepts that are suitable for identifying and explaining recurrent cross-cultural regularities in religious and other concepts are at best very ancillary to any attempt to account for why specific religious traditions take the particular form they do, still less to an attempt to say what if anything we might learn from comparing them, or to the elucidation of concepts such as the Trinity, the Wheel of the Law, or the Dance of Siva. Scholars engaged in these exercises might well gain insights from reading the work of cognitive scientists. A demonstration for instance that on cognitive grounds such and such an idea is more intuitive than another one is an important and interesting finding, especially if cognitive science is able to be more precise and actually quantify such claims,[19] but the way to pursue an inquiry into matters of these kinds is not by the methods of cognitive science. Insofar as the objects of study are the contingent products of human reason, imagination, and will, it will always be a category mistake to try to account for them, as cognitive science must, as instances of general tendencies. For these reasons, the exercises some of our contributors have been tempted into, of trying for instance to explain historical contingencies such as Semitic monotheism, witch-finding crazes, and Captain Cook’s experiences in Hawaii, on the basis of universal cognitive mechanisms, simply cannot succeed. While they could in principle offer specific insights into the general kinds of beliefs that are involved in each case – why cognitively witch beliefs differ from beliefs about sorcery for example – the methods they are using are irrelevant to the questions they would like to try to answer, which are questions about what has happened in human history, not questions about any invariant things to which it has happened. The result of applying methods that are not suited to the question asked is bound to be either generalities that are true, insofar as they are true, of very much more than the specific object of inquiry, and on that account irrelevant to understanding its particularity, or a failure to engage with the details of the case, or both. Where cognitive science strays into trying to use probabilistic claims of general tendencies to account for unique particularities, it will be guilty of irrelevance, or ignoratio elenchi (Oakeshott 1933).

8. Beliefs, reasons, and causes

I began with the observation that in conceiving of human thought under the category of cause, to the exclusion of that of reason, cognitive science makes a powerful and productive methodological simplification, which is also a radical partiality. The consequences of this exclusion can be seen in some of the problems that arise with respect to the category of belief. Much of the complexity that has intrigued and frustrated philosophers and others about belief derives from its reflective character, from the fact that belief is both how we know and also an object of our knowing, which source of complexity is amplified where, as in Christianity, ‘belief’ is also a centrally important category of religious thought, introducing the notion that belief is distinct from knowledge because characterised by certainty, or by doubt, or by peculiar kinds of commitment. In an important essay that showed among other things how unwise a generation of anthropologists had been to neglect the writings of Lévy-Bruhl, Rodney Needham (1972) demonstrated that the category of belief does not correspond to a natural or universal psychological reality, but is instead a specifically post-Christian and not-so-post-Cartesian logical muddle: one that is no doubt now culturally inescapable, at least for users of English, but for all that a challenge rather than a useful tool for any attempt systematically to think about thought. But this is all generally side-stepped in much cognitive science, in favour of a conception of beliefs simply as the distinct mental entities that severally cause specific behaviour, and in favour of the associated practice of inferring the existence of beliefs, conceived in this way, from behaviour by reverse-engineering reasoning.

In an early paper (1982) Dan Sperber distinguished between what he called propositional and semi-propositional representations. He was interested in how to understand what is going on when people appear to hold and act upon apparently irrational beliefs (when a friend comes rushing to tell you of an opportunity to kill a dragon, for example). Sperber observed that there must be a difference in the manner in which we hold a belief (represent a representation) depending on whether or not we understand its meaning. We can hold and in some ways act upon a representation whose meaning we do not or only partly understand – a ‘symbolic’ or semi-propositional representation, in Sperber’s terms – but just because we do not understand its meaning, the ways in which it can inform our thinking and behaviour, and interact with our other beliefs, will be restricted. We believe it in quotation marks: we can recognise the idea, but perhaps only in some forms, we can repeat it and affirm it, but we can only in very limited ways reason or innovate with it, or question it and see where it does and does not apply, and so on.

This paper of Sperber’s is one of very few instances where cognitive scientists have addressed any of the complexities in the concept of belief, rather than taking it for granted, and Astuti’s paper in this volume (2007), in addressing the question of the context-dependency of belief, is another. Most serious thought about belief has been conducted outside the field of cognitive psychology. Paul Veyne’s (1988) brilliant discussion of the terms in which ancient Greeks ‘believed’ in their myths is a case in point, and adds support to the general line of thought Astuti is opening up.

Veyne describes how for half a millennium Greek thinkers grappled with questions of what was and was not reliable in their myths. Noting that even Christians in the later part of his period, who of course denied the existence of the Olympian gods, never questioned the historicity of heroes such as Aeneas, Romulus, Theseus, Heracles, Achilles, or even Dionysus (1988: 40), he emphasises that scepticisms took different forms and were concerned with different matters from those we might expect. Both ancients and moderns, he observes, accept the basic historicity of the Trojan war, although what we know of it comes so overwhelmingly in narratives much of which we know must not be true, but we do so for different reasons.

We believe because of its marvellous aspect; they believed in spite of it. For the Greeks, the Trojan War had existed because a war has nothing of the marvellous about it; if one takes the marvellous out of Homer, the war remains. For the moderns, the war is true because of the fabulous elements with which Homer surrounds it; only an authentic event that moved the national soul gives birth to epic and legend (1988: 60).

In their attempts to sort truth from fiction and lies, the learned of the time seem to us by turns sometimes sceptical and sometimes completely credulous. Veyne doubts that either bad faith or some notion of half-belief explains this. Of course we are familiar with phenomena such as suspension of disbelief, but this again is neither of these. As he remarks, ‘even if we consider Alice and the plays of Racine as fiction, while we are reading them we believe; we weep at the theater’ (1988: 22). It is not that we half-believe or pretend to believe, but rather that we believe, in certain contexts, processes, or practices. And those learned Greeks, Veyne suggests, were similarly wavering or alternating between different criteria of truth (1988: 50). While they might often seem to have half-believed, it was rather that because they regarded myth as a mixed (or half-rotten) corpus, they hesitated between different ways in which they might find the uncorrupted truth in it (1988: 65). The problem was never solved, but in the end Christianization raised other concerns and made it possible to abandon it (1988: 111-2). All along then, argues Veyne, the question of whether and in what ways the Greeks believed in their myths was not a subjective or merely psychological question. Their modalities of belief were related to the definite, socially instituted ways in which truth could be pursued and possessed (1988: 27). People ‘believed’ as they participated in these ways of knowing.

Sperber’s 1982 paper was at least an attempt to begin to address these matters in the language of cognitive science. The distinction he proposed between propositional and semi-propositional representations has however been largely neglected, in favour of a different one drawn by him in a later paper (1997), that between reflective and intuitive beliefs. Reflective beliefs are those we are consciously aware of holding, intuitive beliefs are those that our inherited cognitive architecture causes us to act upon, before and irrespective of any reflection in which we might engage. Barrett (2007) adopts but rephrases this as the distinction between reflective and non-reflective beliefs. With this distinction, matters of qualified or half belief are lost, as is the whole question of context-dependence, for in practice it becomes a distinction between what we think we believe and what we are inescapably caused to and therefore really believe, even if we do not know it.

The idea that we can believe something without knowing we do – indeed something that we believe we do not believe – is now so ingrained in our everyday thinking, largely (and perhaps embarrassingly for most cognitivists) through the influence of Freudianism, that the real force of the claims made with this distinction does not strike us as it should. For all the capacious ambiguity already evident in the concept, it must be doubtful that it is helpful to expand the extension of the word to include postulated facts about the mind that are not on the face of it representations at all. In any case, even if we do allow these unconscious causes to be beliefs, this only re-emphasises Needham’s point. We should not imagine that in saying something is a belief or that someone appears to believe a particular thing, one is saying anything very definite at all. Certainly, in attributing a belief one is not always doing the same thing. Some cognitive scientists, such as Boyer (2005: 26), have concluded that a cognitive study of religion should try to do without the concept of belief, as for different reasons Southwold suggested should anthropology (1983). This would have the advantage that the cognitive mechanisms postulated would not be confused with the mental phenomena they are supposed to explain. Most cognitive scientists, however, use the concept in a distinctive way.

Consider Barrett’s discussion of the human propensity to ‘believe’ in racial stereotypes.

For instance, research suggests it is quite natural to assume non-reflectively (automatically and without conscious awareness) that members of other human groups (e.g., racial, regional, or national) are more alike than people within one’s own group (Hirschfeld, 1996). We refer to this “belief” as a tendency to stereotype. Reflectively we may become convinced that this non-reflective belief is flawed or inaccurate, but if so, the non-reflective belief nevertheless remains (2007: 183-4).

But what the research shows, in so far as it does, is in fact the tendency, and only that, to reason in an essentialist way. The idea that behind this observable tendency, and causing it, there lies a belief with propositional content is actually Barrett’s interpretation,[20] and while he may have good reasons for proffering this, it has costs. To begin with it leaves an ambiguity as to what it is that our cognitive architecture unalterably endows us with. Obviously it is not the particular content of racial stereotypes (the Chinese do this, Indians that); is it even the idea of race in the first place, or does that, like the rest of the content of the racial beliefs people have, come from elsewhere? By rephrasing a statistical tendency (rather than trying to quantify it) as a definite ‘belief’ this crucial question (in addition to questions about the tendency’s magnitude) is obscured. Secondly, the suggestion of definite propositional content makes it possible to think that this (all, as it were) ‘nevertheless remains’, unchanged and impervious to experience. Phrased as a statistical tendency, this would not seem so plausible. Thirdly, rather than pursuing the point that different beliefs may affect us in different situations (as Astuti begins to do), it arbitrarily regards some (those we may never profess, but for which cognitive science has a favoured explanation) as the real and permanent ones.

Another instructive example, also from Barrett (2007: 191-2), is the following.

It is HADD [hyperactive agency detection device] that makes us non-reflectively believe that our computers deliberately try to frustrate us, that strange sounds in a still house are evidence of intruders, and that light patterns on a television screen are people or animals with beliefs and desires. But more relevant to religious belief are situations in which a sheet on a clothesline or a wisp of mist gets recognized as a ghost or spirit.

There is probably no harm in saying, of someone who shakes his fist and shouts at his computer, that he ‘believes’ it is deliberately trying to frustrate him, or that the child who starts awake at an unfamiliar sound ‘believes’ what she hears is an intruder, or that the woman who laughs uproariously at a television programme ‘believes’ she is seeing people and animals being funny. There is positive confusion, however, if we imagine that these ‘believings’ are instances of the same thing. A rage that drives us to our habitual expression of anger, a momentary alarum that quickly passes when we collect our thoughts, and willing participation in institutionalized dramatic illusion are not the same kinds of mental operation. Their various relations to conventions, language, and instituted practices are obviously different. Postulating a faulty device that forces them all upon us does not seem to me to be a promising way to proceed. The fact is, indeed, that all these examples are to some degree conventional. Even if the same cognitive mechanism does turn out to be involved in them all, this would no more explain why they occur, or otherwise explain them, than would identifying the cognition involved in catching a ball explain the game of cricket.

It is a major problem for cognitive science (and especially when it uses reverse-engineering reasoning drawn from evolutionary psychology) that a form of observed behaviour may almost always be accounted for by more than one possible set of beliefs and intentions (Fodor 2005; see also Fodor 2000). So to seek to explain why people do what they do by postulating ‘beliefs’, as causal forces, for which there is no other direct evidence than the behaviour they are invoked to explain, is very narrowly circular. And if this is generally the case, it is even more so of much that pertains to religion, namely ritual action. One of the distinctive features of ritualised action, or so at least Caroline Humphrey and I have argued (Humphrey & Laidlaw 1994: Ch 7), is what we call a disconnection between meaning and form: the fact that different participants (or the same ones on different occasions) seek to attain quite different and even contradictory ends by performing the same ritual actions, because the meaning attributed to a ritualized action is radically underdetermined, as compared even to normal, unritualized action, by the physical form of what is done.[21]

Lanman, in his contribution to this volume (2007), follows the logic of Barrett’s distinction with admirable clarity. Since he regards cognitive-science methods of inferring beliefs from observed behaviour as ‘meticulous’ and ‘robust’ (we can concede at least that they are difficult to falsify), our knowledge of ‘reflective beliefs’ (those people do know they have) seems to him correspondingly flimsy, since all we have is their own reports. This is a common theme in the literature, and given a causal notion of belief, and the fact that of course the clearest examples of ‘unreflective beliefs’ come from instances of people behaving in ways that appear to conflict with their avowed beliefs, this is unsurprising. Lanman finds himself wondering,

If people’s self-reports of their reflective beliefs do not match up with their behaviors and other beliefs, do they actually “believe” what they say or are such statements now to be labeled as merely customary speech behaviors? (2007: 127)[22]

The concerns about the reliability of people’s self-reports that prompt this reflection also motivate Lanman to question Astuti’s experimental data on Vezo beliefs about the afterlife.[23] He conjectures that some of the responses informants gave to her questions were influenced by what are known as ‘social desirability effects’: that is, they said not what they ‘really believed’ but what they thought they ought to think.

Now of course there are cases where people do hypocritically report a belief they do not have, and that they might even despise, but which they know the powerful will reward them for expressing. But this is different from cases where people are genuinely influenced by the opinions of (certain) others, or regard the beliefs (certain) others express as a genuine reason for them to accept (or for that matter to reject) those beliefs. The notion of ‘social desirability effects’ treats these cases as equally suspicious: equally, as Lanman puts it, ‘something that psychologists strive to eliminate from their studies’. But given that a high degree of the latter kind of deference is a prerequisite for anyone ever learning a language, for example, this may be an error of method.

There is no reason to suppose that it is exclusively the hypocritical kind of deference that is at work in the Vezo case. It is likely instead, to judge from the available ethnography, that Astuti’s Vezo informants were telling her what they thought, on reflection, must be the case. They may find it a bit difficult to imagine exactly, and it is certainly not quite common sense, and perhaps it would not take very much to make them reconsider. Certainly, they are to some extent trusting tradition and received opinion in forming the view they do; perhaps they are even conscious that this is what they are doing. After all, they have little directly to go on themselves. This is not a strange or unreasonable position. In any case, none of this changes the fact that they are also exercising their reason and judgement, in deferring in this way. There is no reason for regarding the result as not a ‘genuine’ belief, however much a robustly empiricist self-image might be offended by the way it has been arrived at.

Maybe it is true that in some circumstances, under pressure, they act unthinkingly on instinct and common sense rather than reflective reason. That should be news to no one. But what do we conclude from it?

It depends, to revert to a point I have made before, on the interest that motivates inquiry. Lanman reports, I am sure accurately, that the response of many psychologists is to attempt to select out, or correct for, this tendency of people to exercise reflective reason and judgement in answering a question. Well, insofar as their interest is in the reductive explanation of human behaviour, as of a causal system, which, insofar as it is explained, is thereby amenable to prediction and control, this is a sensible response. But while the causal manipulation of behaviour is an alarmingly prevalent regulative concern in much psychological science,[24] it is not the only possible interest in understanding human thought. Eliminating the free exercise of reason from the purview of your inquiry is, fortunately, not the same as eliminating it from human affairs, and although this method might well achieve some statistically significant predictive measure of how people will behave (although, as I have observed, success in this regard does not in fact seem imminent and has certainly not been secured) this will not make it an exhaustive description of how in fact people do go on.

The important point is that re-classifying human thought and discourse as ‘merely customary speech behaviors’ is not, as it superficially appears to be, a conclusion indicated by experimental evidence. The hypothesis that human reason, imagination, and will are illusory, and that conscious thought and discourse are, as I have heard it put in cognitive-science circles, just the sound of lips flapping about, is instead implicit in the premises of cognitive science as a method. Lanman himself only raises this as a possibility, and does not endorse it as a conclusion, but other cognitive scientists (for instance Palmer and Steadman 2004) have argued for it as the only possible way forward. And it will indeed persistently suggest itself, unless the pragmatic working assumptions for the application of a method are consistently and clearly distinguished from description, or worse still criteria, of reality. As individuals, cognitive scientists can of course resist this alluring confusion of the real with the measurable. They may be as persuaded as anyone else of the reality of human freedom and reason. But if so, it would be well to acknowledge that the methods of cognitive science, since they assume them away, will not be of help in understanding them, and that these features of human life set the limits for the method.

9. Conclusion

Cognitive science can give us an account of some mental operations that are involved in religious thought and action. Just as we may be enlightened by a cognitive-scientific account of what it is to recognise a table or a raccoon, or to mistake an artefact for a living thing, or to see a mirage, or to remember a story, so the same methods can tell us how we remember what we have been told about gods or ghosts, and why we might sometimes think we have seen one. They have given us an intuitively plausible account of why ideas of gods, ghosts, and magic are so ubiquitous in human societies, by explaining why our minds might be highly prone to entertain and retain, and find it so easy to work with, these ideas. But for the evaluative concepts, emotions, and motivations that are not in this sense ‘natural’, but instead the historical products of particular traditions, an adequate account will have to include the history of the language and institutions and relationships and practices that sustain them, and the web of other such concepts on which they depend for their meanings. So if cognitive science can explain why we are disposed to a certain degree to believe in demons, it cannot explain why this demon takes this form in this tradition, or why we find him, say, pathetic. We are at the beginning of developing a scientific account of the computational aspects of human cognition, and this is valuable, interesting in itself, and also something about which students of religion should be informed: just as knowledge of the materials artists work with is useful for historians of art. But however complete and precise its description of those processes might become, cognitive science will never be more than ancillary to and will always be methodologically quite distinct from what anthropological and/or historical students of religion have to do. This means, as I have suggested, that while they can learn from each other’s results, cognitive-scientific and humanistic study of religion are qualitatively different modes of knowledge and experience, and that therefore there is no prospect that one will ever entirely replace the other, or that they might merge into anything other than confusion.

References

Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

– . 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Astuti, Rita. 2007. Ancestors and the Afterlife. In Harvey Whitehouse and James Laidlaw (eds.), Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science. Durham NC: Carolina Academic Press: 161-178.

Barrett, Justin L. 2007. Gods. In Harvey Whitehouse and James Laidlaw (eds.), Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science. Durham NC: Carolina Academic Press: 179-207.

Bering, J. M. 2002. Intuitive Conceptions of Dead Agents’ Minds: The Natural Foundations of Afterlife Beliefs as Phenomenological Boundary. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 2: 263-308.

-. In press. The Folk Psychology of Souls. Behavioral & Brain Sciences.

Bering, J. M. and D. F. Bjorklund. 2004. The Natural Emergence of Reasoning about the Afterlife as a Developmental Regularity. Developmental Psychology, 40: 217-233.

Bloch, Maurice. 2004. Ritual and Deference. In Harvey Whitehouse & James Laidlaw (eds.), Ritual and Memory: Toward a Comparative Anthropology of Religion. Walnut Creek: AltaMira: 65-78.

-. 2005. A Well-Disposed Social Anthropologist’s Problems with Memes. In Essays on Cultural Transmission. London: Berg: 87-102.

Boyer, Pascal. 1994. The Naturalness of Religious Ideas: A Cognitive Theory of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press.

-. 2001. Religion Explained: The Human Instincts that Fashion Gods, Spirits and Ancestors. London: Heinemann.

– . 2002. Why do Gods and Spirits Matter at All? In Ilkka Pyysiäinen & Veikko Anttonen (eds.), Current Approaches in the Cognitive Science of Religion. London: Continuum: 68-92.

– . 2005. A Reductionist Model of Distinct Modes of Religious Transmission. In Harvey Whitehouse & Robert McCauley (eds.), Mind and Religion: Psychological and Cognitive Foundations of Religiosity. Walnut Creek: AltaMira: 3-29.

Boyer, Pascal and Pierre Lienard. In press (2007). Why Ritualized Behavior? Precaution Systems and Action-Parsing in Developmental, Pathological and Cultural Rituals. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Brown, Peter. 1981. The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. London: SCM Press.

Carrithers, Michael. 1990. Jainism and Buddhism as Enduring Historical Streams. Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, 21/2: 141-63.

Cohen, Emma. 2007. Witchcraft and Sorcery. In Harvey Whitehouse and James Laidlaw (eds.), Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science. Durham NC: Carolina Academic Press: 135-160.

Collingwood, R. G. 1994 [1916] Religion and Philosophy. Bristol: Thoemmes Press.

Cort, John E. 2001. Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. New York: Oxford University Press.

Davidson, Donald. 1980. Essays on Actions and Events. Oxford: Clarendon Press.