A new text and a new public

Karin Barber

[Editor’s note: Karin Barber was interviewed by Charles Stafford at the London School of Economics on March 18, 2014.]

AOTC: I’d like to ask about your recent book, Print culture and the first Yoruba novel. In it, we hear the story of a remarkable woman, Segilola. Could you tell us something about her?

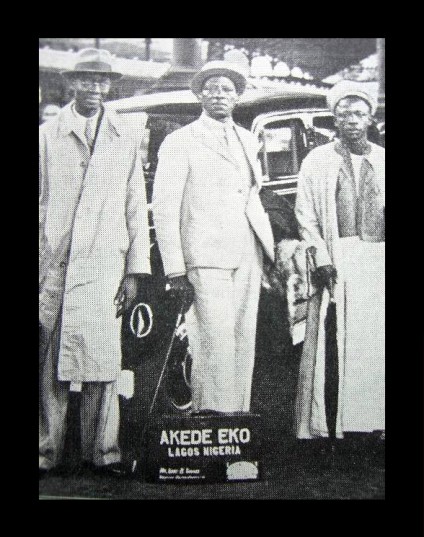

KARIN BARBER: Segilola made her appearance through a series of letters to the editor of a weekly Yoruba-language newspaper called Akede Eko, which means Lagos Herald. This was one of a whole cluster of new Yoruba-language papers that suddenly appeared in the 1920s. In fact, the Herald was the last one of that bunch to start being published, in 1928. Her letters to the editor began in 1929, and they continued more or less every week until March 1930. So for about nine months there was a letter every week from somebody purporting to be called Segilola. But she kept insisting that this wasn’t her real name, it was her nickname, and not a name by which she could actually be identified in the flesh. Her letters were always printed with a title over them which might translate as “The Life Story of Me, Segilola, of the Fascinating Eyes – the One Who Had a Thousand Lovers in her Life.” So you can just imagine what kind of life she was narrating.

She starts off by thanking the editor for giving her this opportunity to tell the story of her life right from the beginning. She says she’s telling it in order to provide a valuable moral lesson to readers, particularly young people, and particularly young women, who can learn from her mistakes. Her principal mistake was to become a good time girl, a “Lagos lady”, a harlot. She started by just being wayward and disobedient, and playing one man off against another. But little by little she became a full-blown prostitute. She became extremely rich, gloried in her incredible power over men, and lived the high life, until she was stricken by disease. And now, as she writes, she’s on the point of death – hideously disfigured by the fatal disease. So she’s writing to provide an awful warning to anybody who might be fancying that kind of career. But she’s also regaling the reader with all the lubricious details.

Now, this story, this narrative, created a tremendous excitement in Lagos at the time. Lots of people began to write in to the newspaper either corroborating the story, endorsing the moral lesson, or, quite often, begging the editor to give the details of Segilola’s real name and address so that they could contact her. One of them actually sent in ten shillings to help alleviate her distress. So the readers of the paper were really captivated by this story and took it very seriously. And they all wrote as if they believed it was true, and the editor himself did everything he could to corroborate this impression. So he described how this woman came to his office one Saturday evening, with tears in her eyes, begging him to publish the story of her life. And all kinds of little details were added to bolster the impression that it was a real woman who came, and that he, the editor, helped her to put the letters into readable prose and then published them for her.

And it only gradually emerged, afterwards, that it was all a fiction – a fiction written by the editor of the newspaper, I.B.Thomas. It went through several editions and in retrospect the Yoruba literary establishment sees this as the first Yoruba novel.

AOTC: So it was published as a book.

KB: Yes, soon after it had been serialised, in July 1930. And then it rapidly went into a second edition, and then in the 1950s it went into a third edition. And each edition is slightly different from the preceding one, which makes editing it – as I’ve done for Print culture, which contains the full text – very fiddly. The differences are small but pervasive. You can never be sure which of them are mistakes and which are intended to be improvements. So it was quite hard deciding on a definitive text. But the joy of this edition was that I was able to include a lot of the reader’s letters, the editorials, and a tremendous jeremiad from another newspaper that denounced the whole thing – saying that it was absolutely vile, filthy, disgusting, and shouldn’t have been published at all! So I’ve included lots of response from readers and other writers.

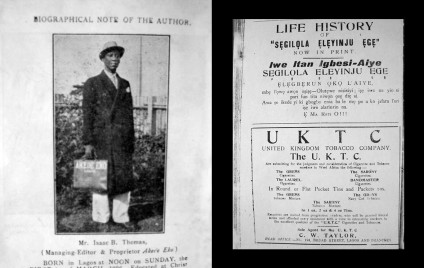

I. B. Thomas and an advertisement for his book.

AOTC: But how did you do the research for this project – was it mostly archival? Or were there people around that you could talk with?

KB: It was almost entirely archival, until after I’d finished it. The only place where I could find these newspapers was in the Nigerian National Archive, and I spent some weeks photocopying everything that seemed relevant to the emergence of the story. And then I spent several years trying to decipher it, and asking people for any clues they could offer about local idioms and allusions that are no longer current.

So I regarded it as a kind of ethnography of the past. I was trying to do an ethnographic type of project rather than a purely historical one. I was trying to trace how things happen, how things emerge, how new cultural forms take shape in action, and how it is that some of them fail, some don’t take shape. What makes a difference? How do some things catch on and gather strength, and other things are experimented with and then abandoned? And it seems to me that that is what ethnography in a very broad sense allows you to do: see the things that seem possible at the time, even if from a retrospective point of view they haven’t been folded into the narrative of the success stories. Nonetheless they were possibilities at that moment. And there were lots of moments at which it seemed that this story wouldn’t take off and be completed. The newspaper might collapse, because it was very much a hand to mouth affair, and Segilola spent a lot of time stoking fears that she herself would die in the middle of it (although of course that was a fiction). But this idea that it was precarious and that it needed support ran through it all the way. And the sponsorship or response from the audience is, in a way, what enabled the story to be finished off.

Actually there had been another serialised narrative in another Yoruba paper, a rival paper, which had started three years earlier. And it was also, interestingly enough, a story in a woman’s voice, and it was equally fictional. But the author of that text didn’t pretend that it was true – it was announced as a fiction at the beginning. It went through 12 episodes, and then the author – who was the editor of that paper – suddenly announced that “pressure of business doesn’t allow me to carry on with this.” And there doesn’t appear to have been any correspondence to the paper asking him to come back and finish it! But he did come back about two years later and he wrote some more episodes, almost to the end.

It’s interesting that this other story is a kind of mirror image of Segilola. It’s about a good girl, an orphan who starts life very disadvantaged, does everything right and ends up marrying the king and having wonderful offspring who are all brilliant, and all go to Oxford and become lawyers and doctors. Total success. Whereas Segilola is the inversion of that: born of a good family, she does everything wrong, and ends up not only destitute but “without so much as a finger to call a child” – she has nobody. So in a sense it was the same story only the other way round, but it was much more popular. And it got this response that enabled it to take off whereas the story of the good girl didn’t seem to get much response. It was only after Segilola had been published as a book that the author of the story of the good girl hurried up and added the final couple of episodes and brought that out as a book too – but he was pipped to the post by Segilola. So the support, the feedback, seemed to me to really be part of the evolution of the text. It’s not something that happens afterwards, it’s something that enables the text to be produced and to be completed in the first place.

AOTC: As you’ve already said, this is now taken to be the first Yoruba novel. The interest of Segilola’s story is clear, and perhaps for readers her failure story is more interesting than the success story. But what about the skill of the respective writers? Would experts in this genre say that the writer of the Segilola story is actually a better writer, i.e. it’s not just that his story is better but that he does a better job of telling it?

KB: It’s a much more gripping narrative. It’s highly emotional, very life-like. Segilola sometimes becomes almost incoherent with emotion. But she also constantly references popular culture, popular songs, anecdotes, etc. You know I said that my work was based on archival research until after I’d finished it. I was launching the book in Lagos, and I was invited to give a lecture at the Lagos State University. And I was talking about how I. B. Thomas, the author, alluded to many popular narratives without actually telling the narratives. So he was assuming that the reader brought a certain amount of local knowledge to bear on the text. And one such example was a reference to a little popular song, which Segilola said had been composed ten years after her wedding. She’s trying to give us clues about the date of her wedding without actually telling us the date. So ten years after the date of her wedding there was a famous incident which shook Lagos to its foundations. And this was the occasion when an old man climbed onto his rooftop and started shooting at passers-by. There was a song composed about this at the time: “Yesufa, the hunter of human beings”. So I quoted this song, in my lecture, to illustrate the way that I. B. Thomas used popular knowledge. And suddenly the whole auditorium, about 400 people, starting singing it! They remembered it of course. So there is a lot of local knowledge still extant about the culture from which this book came. A lot has also been forgotten, obviously. But it was very much a living urban popular culture that I. B. Thomas drew on, whereas the other book is much more conventional and limited in the materials it draws on.

AOTC: So it is in fact a skilful narrative.

KB: Very skilful and very heterogeneous. It draws on lots of different genres to build this new form: letters, sermons, editorials, all kinds of material. But the interesting question is how do people take all these ingredients and precipitate something that hasn’t been seen before? Why does that combination of things take off whereas other things might not?

AOTC: So who was I. B. Thomas?

KB: He was a member of the Lagos elite of the time. It was the elite who owned and published these newspapers, both English and Yoruba. But I would say he’s probably on the fringes of the elite. He was educated up to the equivalent of maybe two years of secondary modern school. So he wasn’t as highly educated as the leading elite people. However, he was fervently Christian and set great store by literacy and schooling. He worked as a pupil-teacher after leaving school, and rose up the ranks to become the headmaster of a primary school. He gave that up and became a cashier for an expatriate business, and then he became a journalist and newspaper editor. He was tireless, very entrepreneurial. He promoted his newspaper all over the place, and went on long journeys into the hinterland and established connections with people who would then subscribe to the paper and send in little snippets of social news for publication. And eventually he became quite well known and was even included in a delegation of Nigerian newspaper editors that paid a visit to Britain in the 1940s. He became a respected and well-known figure. But he was very much a self-made man. He experimented, tried his hand at lots of things.

AOTC: Could one say that his primary motivation in this case was a commercial one, i.e. that the Segilola story was his way of saving his newspaper?

KB: Who can say what the primary motivation was? The Yoruba-language newspaper editors all said that their purpose was to benefit the community. So they were producing newspapers not to make a huge income but to promote the progress of the city, to represent public opinion, to reach out to people who couldn’t read the English language newspapers. That was a big thing in the 1920s, a desire of the elite to widen their popular base, and this they could only do by writing in Yoruba. So it had political, although not necessarily party political, motivations: to show that they represented a bigger constituency than just the very small English-speaking elite. So it was partly that. And partly, yes, he did want to sell his paper and make a living from it. This kind of sensational story certainly sold newspapers. It was also very didactic. The purpose was to edify the reader. Every single letter includes edifying messages. But the readers’ responses suggest that this was part of its attraction and one of the reasons for its success – readers wanted a moral lesson that they could apply to their own lives.

AOTC: I’ve heard you say that part of what interests you in this text is the combination of almost hackneyed moral sentiments with this very innovative way of presenting the material. So it’s a funny combination of being highly conventional and highly unconventional at the same time.

KB: And what this allows I.B.Thomas to do, which is really innovative, is to bring in this shared popular culture, which the English language papers had no truck with at all. They remained very conventional: they didn’t experiment with genres. All through the 1920s they remained formal and very proper. They wrote this marvellous Victorian type of prose. They were masters of the art. But they didn’t deviate from what they thought was the proper way to write, whereas the Yoruba language authors – it was wide open for them. There was no standard way of writing a Yoruba language newspaper and they could draw on all kinds of popular genres, popular knowledge, which they could then reshape in different ways. So it was partly this move to bring in a wider audience who could read Yoruba but not English – which, by the way, was a large constituency in Lagos at that time, about 20,000 people, I’ve estimated from the 1921 census. So this was a waiting audience who were very eager to read Yoruba papers when they were put into circulation. And to reach them you could use and reshape the popular genres that they knew. So it was breaking new ground.

There was another paper, The Yoruba News, published in Ibadan, which was very much dedicated to retrieving and re-publishing oral traditions – hallowed, respected oral traditions like praise poetry – as well as very fine modern written poetry. But the Lagos papers entered into a seam of popular culture which was more like urban folklore. They gave relatively little space to the major, ancient Yoruba genres and much more space to things that might have been popular twenty or thirty years before, drawn from urban folklore and not from ancient traditions. Which meant they were much more experimental, because all this stuff was relatively new, relatively informal, relatively unrespectable.

AOTC: So presumably you’ve done the hard work of pulling all of this together and publishing a new edition of the book with additional resources and commentary not just because it’s an intrinsically good thing to do but because for you the material gets at interesting questions about popular culture, media at particular historical moments, the use of different genres in writing, etc. So a range of themes you’re interested in come together in this particular case – right?

KB: My interest is focused on two things. One is how new textual genres form, which you can take as a central instance of how new things in general are created socially. But the other thing, which is inseparable from the question of how new genres are formed, is how new publics are evoked. And that’s to do with how people imagine themselves as being together socially, and how that imagination changes. And the way people are addressed in texts gives clues about how people are imagining the possibilities of a constituency existing at that time. In fact these Lagos papers invoked layers and layers of collectivities. So the public wasn’t just one general public. It was partly about known people who could be addressed individually, by name, within the papers. And then it was categories of people, like “you, young women” who might benefit from this story. And then there was all the Lagosian knowledge, which depends on having a Lagos readership, and then they are continually also addressing anybody who can read Yoruba, and even far beyond that. The newspapers kept writing as if they could address “the four corners of the world”. So they had this imagination of print as being able to reach literally anywhere, everywhere, something which was obviously highly exciting to them. So although they were drawing so much on live, present, oral popular culture, they were also imagining convening this enormous, unknown, in principle indefinitely extensive, public. And they enjoyed imagining that public’s existence.

Actually, I should add that my work on this book is part of a bigger project that I am still doing, on early Yoruba print culture much more generally: books, histories, pamphlets, poetry, etc. But here you can see how the funding system of the UK causes people to focus on some things and not other things. I was applying for one of these AHRC research leave grants which allow you to extend a short period of study leave into a slightly longer one. A very strong requirement for this, however, is that you have to have already started the project, and you have to have finished it within the time that the AHRC funds. It’s very hard to think of a project that you can finish in that time, so I didn’t know what to do. The print culture project was what I wanted to do, but it’s huge.

Then my friend and collaborator in a network that we’re running – the African Print Cultures Network – this friend, Stephanie Newell, who is a very distinguished Professor of English at Sussex, said why didn’t I translate and do an edition of Segilola which she’d often heard me talk about. In fact, she’s now written a wonderful book in which she uses the story – from a different perspective from mine – in one of her chapters. So that’s why I decided to do this particular book, and then of course it got out of control. Partly because when I started to look at all the newspapers published around the time of the serialization of Segilola, I discovered all this other material, such as feedback from readers, which I knew existed, but I didn’t know how massive it was. And I was very lucky because Brill, who published the book, were very indulgent. They allowed me to expand the proposed book: it doubled in size from the time they accepted the proposal. Not to mention that it has masses of Yoruba language with facing translations, which most publishers don’t like.

So this bigger project on Yoruba print culture is connected with our Network, which involves historians, literary scholars and anthropologists who work on Eastern, Southern and Western Africa. Actually, it’s one of those instances where it’s a topic you couldn’t do without a network, i.e. because the topic itself is a network. These newspapers were in communication with each other, including with West Indian publications and publications from African-Americans. So there was a trans-Atlantic network, as well as a network within West Africa, and there were also similar things happening apparently independently in Eastern, Southern and Western Africa. It’s a series of partly-interconnected histories that no single scholar could possibly study on their own. So we put together a network to study a network. And the interdisciplinarity of it is also interesting to me. I’ve always done interdisciplinary work by choice, but I do think certain topics really require it. On this project, I don’t feel any friction at all between the different interdisciplinary perspectives, they all seem to complement each other.

AOTC: So, you have an unusual CV for a UK-based academic. You spent a lot of time in Nigeria – your PhD is from there, and then you lived and worked there as an academic for a number of years, and you were also heavily involved in performance activities there. I wonder at this stage in your career, looking back, how you feel about this trajectory? Actually, I also wonder if anybody today could get away with your career trajectory, i.e. because it’s such a non-standard one.

KB: I don’t think it would really work to try to do it now. In fact, I think it probably had some drawbacks even then. I did my PhD at the University of Ife, and I thought that was a good thing at the time, because I knew my research topic was going to be very focused on the acquisition of language. Not that I wanted to do linguistics, but I wanted to immerse myself in verbal texts. And all my projects, starting from my PhD, have been on one type of verbal text or another. The first one was praise poetry, for which I spent more than three years living in Okuku, a small town in central Yorubaland. I found there were lots of different genres all based on praise-epithets: they were in the air, their performance in different modes and styles was ubiquitous and was fundamental to almost every event and practice concerned with social well-being and self-realisation. The second project was popular travelling theatre, which at the time was an astonishingly huge and vibrant cultural phenomenon, with more than a hundred professional, commercial theatre companies plying the roads. I joined one of them and travelled with them whenever I could over a period of three years. That introduced me to different registers of Yoruba and inducted me into the art of improvising in front of ebullient, noisy, youthful crowds in a packed auditorium. Since then I’ve worked on various other genres. I knew that in order to do that kind of work you have to spend more than the statutory twelve months – which has now been whittled down by all kinds of pressures. Many students now don’t even get to spend a whole twelve months in doing their fieldwork.

AOTC: Luckily, most of our students still do eighteen months or two years.

KB: That’s fantastic. But it’s very hard, because of funding body strictures, as you know. So I was happy to be able to spend years in the thick of Yoruba life. After I’d done my PhD fieldwork, what happened was just that I got immersed and involved, and I really enjoyed it. I was very happy and honoured to get a job at the Department of African Languages and Literatures at Ife, because it was a Yoruba-medium department. So to be allowed into that very august body, full of real experts in Yoruba language and literature, when I was a beginner, seemed to me incredible. And it was. For me as a learner it was incredible to have to teach courses and deliver lectures in Yoruba. I learned a huge amount from my colleagues, from my students, and just from going around every day. So it was completely engrossing and fascinating.

But it certainly wasn’t undertaken with any idea of career progression. I had no idea what you do to have a career. Things weren’t really mapped out in the clear way that they are now. Now people know that by this stage they have to have got a book in press, and by this stage they should have six articles in peer-reviewed journals, all those kinds of milestones – I had no idea whatsoever. And of course the longer I stayed in Nigeria the less idea I had of what my coevals were doing in the UK . In lots of ways it was wonderful and great, but it has also caused me to end up with a rather peculiar profile.

AOTC: In relation to all of this, I wanted to ask you about expertise. I do feel that hearing your trajectory, and the amount of time you’ve spent embedded in a very particular setting, and involved in things like performance troupes – that’s a level of involvement and also a time-scale of involvement that most of us can’t match. So I basically wonder how patient you are with novices – I mean, a lot of anthropology is premised on a lack of expertise, and the fact that you don’t know very much is acceptable. I wonder how you cope with students, for example, who are going to go off to Nigeria but have no idea.

KB: Well, it’s always going to be premised on a lack of knowledge. One becomes more and more aware of this the longer one goes on. Now I feel that I’m just beginning. Which is a funny thing to say when you’re on the point of retiring! There is so much I’d like to learn. I don’t think you ever say “I’ve done it”.

Please join our mailing list to receive notification of new issues