Post-feminism and other historical condundrums

Sherry B. Ortner

[Sherry Ortner was interviewed by Charles Stafford in Los Angeles on 10 November 2014.]

AOTC: I’ve been reading your recent article, “Too soon for post-feminism”, in which you use some material from your work over the past few years on independent films and filmmakers. Could you explain what prompted you to write that piece?[1]

Sherry Ortner: I had been thinking about it for a long time. I began from a sense, an almost paranoid sense, that patriarchy is everywhere still and yet nobody is talking about it. And it’s there in some particularly nasty forms, too, it seemed to me, worse than ever. I don’t know if the situation really is worse, but watching the films I talk about in the article – they help you focus on what you’re not necessarily seeing. Documentary filmmakers, that’s often what they do: they go rooting around, looking for the difficult issues that we’re not talking about. I love the genre. So the paper is partly an attempt to get people’s attention focused on the patriarchal forms of power still at work in contemporary society, using examples from films.

AOTC: When you say that people are “not talking about patriarchy”, you obviously have post-feminism at least partly in mind. Could you explain a bit more what you mean with respect to that?

SO: I’m not sure how much this will resonate outside of the US. What is now labeled as post-feminism in the US started out from the perception among an older generation of feminists from the 70s and 80s that young women today didn’t want to have anything to do with the earlier feminist movement. The word feminism was somehow tainted. Students didn’t want to talk about it – certainly not the younger women whom we as academics were encountering in our classrooms. Even young women who feel that there are problems out there don’t want to identify themselves with the movement in the particular form that it had in the 70s and 80s. It’s seen as anti-male. They’re afraid they will be labeled as lesbians. And it seems to them unfeminine, somehow, whereas young women want to feel attractive, to dress in feminine ways, things like that. So there’s a whole generational shift in attitudes about being female.

But for me, a contribution of the paper is actually pulling together some other phenomena and putting them in the same basket as this issue about generational change. Because what we’ve also seen in academic anthropology, in writing by senior scholars who themselves used to identify as feminists, is a kind of drawing back from that, for example in resisting the application of feminist ideas to women of other cultures, resisting the idea of deploying the notion of patriarchy in relation to other cultures, etc. It’s very messy, but what I felt was useful was to put these things together in one package, to point out that post-feminism is coming from several different directions. The third strand, by the way, was coming from left feminism: saying that, unfortunately, in so far as we still have any feminism left at all, it is a kind of neoliberal feminism, what we see with someone like Facebook executive and billionaire Sheryl Sandberg – this super get-ahead female executive sort of person, who sees herself as a feminist. So the charge that feminism has been absorbed by neoliberalism, that’s a third element of post-feminism. I wanted to put these things together in one frame.

AOTC: One of the points you make is that some people seem to have stopped thinking of patriarchy as – specifically – a system of power. That’s what you’re highlighting: that it is actually there systemically. And some things that may not feel like patriarchy per se, or be labeled as patriarchy, actually are patriarchal.

Illustration by Ed Linfoot/Vladgrin/Shutterstock

SO: Right. Just bringing back the word patriarchy can be a good thing. It hasn’t been around, everybody stopped using the word. But actually it’s a good word. It goes to the point that this is not a matter of just some retrograde individual men, but an ongoing system of power. But in response to your point about things not seeming patriarchal: I do think it’s important to shift away from the focus being so much on the family. The patriarchy idea is mostly seen in relation to family and kinship and fathers – real fathers as patriarchs. And especially in middle-class American families, women don’t especially feel this any more. Most of us don’t come from that kind of background. And it’s also the most sensitive issue cross-culturally. If you start targeting other people’s families, it touches them deeply. So pushing the question of patriarchy up into the macro structure was a key thing for the paper: to get it off the family topic and up into corporations and so on.

AOTC: That is an interesting point for me. I grew up in a relatively conservative, patriarchal environment, but surrounded by very strong women who were super capable. And then as an anthropologist I went to rural China, a textbook case of a patriarchal society, but again I found myself surrounded by strong and capable women. So the idea of women as weak victims didn’t resonate at all. I’ve even written a paper about this, called “Actually existing Chinese matriarchy”, in which I say that if we want to theorise Chinese patriarchy we need to theorise actually existing matriarchy too. But the point you’ve just made in relation to family is essential: there’s a big difference between the flow of family and communal life and the structure of power in society more broadly.

SO: Right. A lot of women don’t feel oppressed. In terms of their everyday lives, they feel they have power, they feel they have agency, they’re not victims. So to push the patriarchy idea cross-culturally goes against a lot of peoples’ subjective experiences. On the other hand, if you point to the macro structure…

AOTC: Yes – China is a clear case of that. You’ve got very clear discrimination against women across some of the most important domains of life.

SO: Exactly.

AOTC: You know, I made the point about Chinese “matriarchy” to try to push others to theorise this. And I had people saying “That’s great: I agree with you that women in China have a lot of power!” Or I had them objecting to what I said, because it came across as an anti-feminist point to make. Whereas my point is that to understand patriarchy you have to theorise that “matriarchal” bit of it – at least in relation to these places I’ve been where women are so flagrantly strong, great, funny, etc., in everyday life.

SO: I think what you’re saying is quite important.

AOTC: So in your article you set up these different strands of post-feminism and bring them together, but the empirical content you work through in the second half of the paper relates to three films: one about a mining community, one about the military, and one about a corporation.

SO: The strategy of pulling films together to highlight some themes I want to talk about is something that emerged from my film project, and I find it enormously useful. The first of the three films is North Country, about a woman who goes to work in the iron mines of Minnesota in the late 80s. This was a feature [i.e., fiction] film based on a true story, about the legal case that developed from her experience.[2] The second one was a documentary about rape in the military.[3] The third one was a documentary about the Enron corporate scandal.[4] The strategy was to pull together films in this way when you’re trying to talk about a big issue in a big society – a case where you can’t possibly do ethnography to get at all of the big patterns and questions that are out there. I’ve used non-fiction films in particular as a strategy for trying to see what we can’t easily see.

AOTC: But could I push you on that a bit? We know from your latest book, Not Hollywood, that you’ve now done a lot of ethnographic work with the people who actually make films of these kinds, ones with a progressive agenda behind them.[5] It’s not as if you’re a random viewer of these films. You know a lot about the thinking that goes into them, and actually the production.

SO: So I do, and I have, and by now I feel that I know quite a lot about that. I started in 2005 – that’s 9 years now in the process. But in this particular paper I pretty much just use the films as texts as if they were mini-ethnographies.

AOTC: Right. And what you do with the films goes back to your point that something you might not call patriarchal per se actually turns out to be so. Could you give an example of that from these films? I suppose that Enron: the Smartest Guys in the Room, is the most obvious.

SO: Yes, because it’s the least obviously patriarchal, at least at first glance. It all seems to be about money and corporate crime and so forth, but it doesn’t take much digging to see the way the whole thing is highly gendered in terms of masculine power.

AOTC: So in the end with this article you’re trying to say something general about America, taking it up to the level of the military, corporations, etc., you’re ratcheting up to that level. And for you the bottom line is that America is patriarchal, post-feminism notwithstanding, and that recovering a kind of feminism now is essential.

SO: Right, that’s the message. But what is a new feminism going to look like? I think it has to look like something different because people are not on board with the old feminism any more. It has to be some new kind of movement and I think it’s going to be hard to get that to happen because there are so many other terrible things going on in terms of the economy and the environment. I don’t agree with the idea that these other things are “more important”. But on the other hand they seem more urgent: you know, we have to do something about the environment, about neo-liberalism, right now. But if you think of these bigger structural entities – corporations and so forth – that are forwarding these bad agendas that need to be resisted, they’re not just politically and economically bad. They are patriarchal through and through. So this is just my little voice saying that we need to think about this. The place I actually see something starting to change is in connection with the issue of sexual violence on university campuses.

AOTC: The whole business of student athletes being involved in this is interesting and important. It’s really touching on big American issues about sex, sports, identity, race – it’s obviously very complex.

SO: The race issue complicates it right away. Lots of difficult cross-cutting issues.

AOTC: I suppose if you want to be politically motivated, the fact that it’s complicated or even dangerous is good. This is going to be a mess, but it’s better than having things be straightforward so everybody can think of it as a simple problem to solve. For better or worse, this is going to be pushing all kinds of buttons.

SO: Exactly.

AOTC: Ok, let’s step back from your recent paper, which is just one paper in a long career in which you’ve done many things. I wanted to ask you about the differences between your projects. I suppose one thing is that if you think about your Sherpa work, your New Jersey work, and your recent work on film, these must have been radically different experiences for you as an anthropologist – yes? In terms of methods they certainly draw on very different methods.

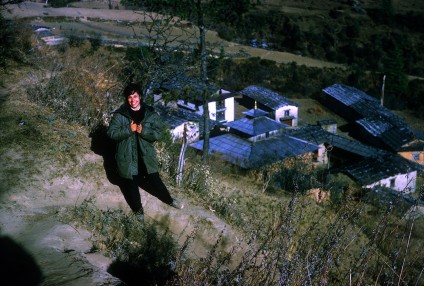

SO: The Sherpa work, which was really twenty years of work, itself actually went through different methodological stages. The first one was absolutely classic fieldwork. I went to one village, I sat there, I talked to everybody. It was far away, it was exotic, it was hard to get to – and I’m really, really glad I did it. I wrote the dissertation, which is something that I hope nobody ever looks at. And then I wrote the book about it from scratch. I scrapped everything except one chapter of the dissertation. But it was pretty classic fieldwork, and it was very much getting into the nitty-gritty of village life, and into “culture” in the classic sense: how these folks in this context see the world. I came back from fieldwork and even as I was writing the book things were changing so much. The book came out in 1978.[6] I was not unhappy with it, but I felt there was so much that was not there, and that needed to be looked at and thought about.

Sherry Ortner during her first fieldwork

Particularly history was missing. To me that was a huge question. Everything I saw in the field the first time, I took for granted – somehow it seemed it had been there since the beginning of time. I never asked about the history of anything. But I was writing a paper after the book was finished, about my original idea for the PhD research. When I went to the field my original proposal was about shamanism, and about the relationship between shamanism and the Buddhist religious system. And then I got there and shamanism was almost extinct. What I found were ex-shamans, retired shamans, so I changed my project. Still, I did interview all those ex-shamans, and I put the data away and then later I thought I should look at it again. And I realized it had never occurred to me to ask why the shamans were in decline. It sounds crazy, but it never occurred to me to ask historical questions. There used to be shamanism, now it’s not here anymore, what happened? Basically I assumed some kind of simple “modernization” answer, which of course tells you very little.

So I became much more interested in history. I even went back through my fieldnotes from the first project and I found people saying historical things that I wasn’t hearing. I wrote them down but they weren’t registering in my brain. So my second project was primarily oral history and I asked all these kinds of questions. People were still alive when some of the major religious events took place, and had all sorts of memories, so I was able to reconstruct an oral history of Sherpa religion. That was the second book.[7]

And then the third project: I came to feel that I had never talked about Sherpas and mountain climbing and, well, that’s what has come to define them in the modern world. The first time I went into the field, it was the time of the Great Cultural Revolution in China and the mountains were closed – the border was closed. The Nepal government was afraid of border violations with China and they shut the border, so there was no climbing. Which was a hardship for the Sherpas, who had already come to be quite economically dependent on it – not as much as later, but a fair amount. So that was one reason I had not paid attention to it, but a second was just a kind of orneriness on my part. Like, well, everybody thinks of the Sherpas as mountain climbers but I’m going to show that they have another life. But by the third book I thought I really have to write about the mountain climbing.[8] That research was partly based on some oral histories but also on a huge amount of working through old mountaineering reports. Everything was published, there was no real archival research, but fortunately mountaineering was a very literate type of activity from the beginning. There were records of everything. So that was a combination of oral history and old documents that you had to go searching to find.

AOTC: So in a sense, the leap between the Sherpas and New Jersey is not as huge as it might seem.

SO: Right. That’s what I’m saying. At a methodological level, it’s not a leap, although each project was a step beyond what I did before. But it was not from “my village in Nepal” to “a Hollywood film set”, not that kind of leap. Really, the big change, the huge break, was when I decided to start working in the US, and then having to read the literature. It’s voluminous. When I went to Nepal there was one book on the Sherpas. I read the book, I was ready to go. It wasn’t quite that simple but it was close. But the sociology of the US is huge. So really I had to do just area reading, it wasn’t like I had to retrain myself anthropologically, but it was a new area with so much literature. I took two years off to read the material about the US, especially about social class because I wanted to look at class. So it was a big retraining, that was the main thing. And I had to stop working on Nepal – I couldn’t do both things.

AOTC: And the New Jersey work was the next thing, there wasn’t some other project you did in between?

SO: Right.

AOTC: And was that exciting, refreshing? Personally I think New Jersey Dreaming is such a good book, I often tell people to read it.[9] You get the feeling that somehow the shift was very intellectually stimulating for you. Is that right, or was it all a terrible struggle?

SO: No, no, you’re right. I didn’t realize it came across in the book. I was very uncertain about studying my high school graduating class. I was very ambivalent. When I left for college and moved away from New Jersey I thought you wouldn’t get me back there with wild horses. I thought that if some job in New Jersey was the last anthropology job on earth I would not take it. I felt like I just broke out. So I wasn’t sure I could do the project there – I had such complicated feelings. I said to myself, let’s see, and I signed up to go to a reunion, the 30th reunion. I had not stayed in touch with people, I had completely cut things off. So I went to this reunion and I was dreading it, but it turned out to be very stimulating, and in fact kind of amazing to talk to people with whom I had shared the first part of my life. We all knew where we were coming from. So it turned out to be much more pleasant than I had expected and then I committed to the project. Doing the project itself was – well, actually, on a methodological level it isn’t that far away from where I started, because I had already been doing a lot of oral history, but nevertheless it was a different kind of fieldwork. Multi-sited and all over the place. I had a terrific time doing it.

Some of the yearbook staff from Sherry Ortner’s high school class – including Ortner herself.

AOTC: One of the things I find thought provoking about the work is that it’s almost like a case of reverse engineering. The outcome has happened. You’ve got the outcome. And one of the big problems in anthropology is that we watch many interesting processes, e.g. we see kids growing up, but we have no idea what will happen to them. Whereas in your case you’re starting where the fateful life things have unfolded, however they’ve unfolded, and you’re getting people to reflect on how they ended up there. In that sense, it’ s a poignant work.

SO: Right. People were so reflective. I just loved listening to them in interviews. And people who – I’m ashamed to say – I really didn’t pay any attention to in high school turned out to be really thoughtful people who had wonderful things to say, or had had fascinating lives, good and bad. But your point about reverse engineering, I would say that’s what I’ve been doing – on some level – since the shamanism paper I was just talking about. In other words, this was about realizing that everything we see as anthropologists is actually an outcome of a history. And that’s the question: how did we get from there to here? For sure, that became a key question for me, starting right after Sherpas through their rituals. So in that sense there is some real continuity to my work.

AOTC: As for the film project, did that emerge while the New Jersey project was still being done?

SO: No, I finished the New Jersey project with nothing in mind: I did not know where I was going next. I knew I had to stay in the US because I had invested way too much effort by that time to do something else. But it started before I moved to California. It wasn’t that I got to Los Angeles and said, oh, now it’s time to study film. I was thinking of it in New York, when I was still at Columbia. I was casting around: here we are in the US, what are people not thinking about, not talking about, in the world of anthropology? There was more and more work being done in the US, so it’s not like I was the pioneer, but I was trying to think about the empty spaces. Also, the second element in this is that New Jersey Dreaming was very sociological, you know, a study of people on the ground – what happened to them, as well as a lot of quotes that came directly out of people’s mouths. I felt I wanted to get back to cultural issues, the meanings and values that are built into the larger world we live in. But how to do that? Culture had become such a contested concept. So my plans moved toward the question of cultural production, the question of where and how what we think of as “American culture” is actually produced. This led me to start thinking about Hollywood, which had been studied in the 1940s by Hortense Powdermaker –

AOTC: Who you talk about in the book.

SO: Right. I actually thought to write something more about her – she’s an American woman from an “upper” German-Jewish background, not your Eastern European Jewish peasants, which is my background. A native New Yorker, a Manhattanite, from the sort of background, you know, the people who gave you Goldman Sachs, that type of Jewish aristocracy. She went to London and studied anthropology at the LSE with Malinowski and she took her degree and then came back and founded the department of Anthropology at Queen’s College in New York. There are a lot of missing links, but it’s an interesting history there, and then she did all these diverse projects, including in Hollywood.[10] I met somebody who told me that she had been interested in Powdermaker, and had done some inquiring. And it turned out that Powdermaker’s personal papers and fieldnotes, everything, had been destroyed for the following reason: she had followed the case of Malinowki’s diary and was appalled at the way he was exposed through the diary’s publication. She felt it was never intended for publication, and shouldn’t have been, and she therefore instructed her sister to burn all her papers after she died. And the sister did it. So there’s nothing left. But it turned out that Sydel Silverman found some letters from Powdermaker in the files at the Wenner-Gren Foundation, because they had funded some of her fieldwork, including her work in Hollywood. It’s so interesting but unfortunately we can’t recover most of the papers.

AOTC: So against this background you were thinking about doing something on film, but hadn’t decided.

SO: Yes. Also, I had ideas, as I said, related to the undermining of the traditional culture concept in American anthropology. The sense that what we used to call culture, the idea that people share a world view – that it’s much more fragmentary and diverse than we had assumed. There was a whole shaking up of the culture concept, as you know, and for me this really focused attention on the question of cultural production. The idea that culture is not only this thing in the air all around us, that we just soak up as children, but that at least some of it is being actively produced somewhere and being put out there in the airwaves. So that was one theoretical opening for me to turn to Hollywood

AOTC: As you explain in Not Hollywood, you actually ended up working in the world of independent film rather than mainstream Hollywood, and that is the part of the film production world that is progressive, in political terms, but also very self-reflective in terms of what they do. It sounds incredibly interesting, but remind me why you ended up doing that?

SO: I couldn’t get into the big Hollywood studios. I spent a year, once we moved to Los Angeles, tapping every contact I could find. I was going to do a Powdermaker redux, basically, with a twist of historicizing it. But I couldn’t get into Hollywood, it was a brick wall. I spent a year. I remember weeping in frustration. But in the course of that, everybody would give me some contact here or there who would talk to me. “Oh well, you can’t talk to Mr. Big over here in the studio but you can talk to my friend the screenwriter.” So I’d say sure, because I’d take anything. I talked to all kinds of random people in the beginning. A fair number of those random people were attached to the independent film world and that’s why they were available, they weren’t barricaded behind the lawyers like the studio people. One of the reasons the studio people don’t want to talk to you is that they are terrified. The old Hollywood studios have all been bought up by large corporations, where there’s a corporate party line.

AOTC: I guess it’s also true that the kinds of films that you’re able to draw on for the kind of article we started with – your recent piece about post-feminism – those things are being done effectively by precisely these kinds of filmmakers.

SO: The whole question of politics in American film is really interesting. Unlike a lot of European filmmakers, who embrace a kind of political agenda, the American movie industry has a history of shying away from politics, basically since the Cold War and the McCarthy era in the Fifties. Hollywood was targeted in that era as a hotbed of Communism, and a lot of people in the industry were persecuted. So Hollywood movies became very bland in terms of politics, among other things. And even in the world of independent film, that sees itself as absolutely “not Hollywood,” a lot of independent filmmakers would deny being “political” – that’s still a negative word. It’s only when you get to the documentary filmmakers that at least some of them would acknowledge that they are making films with a political agenda.

Yet all independent filmmakers see themselves as making films that go against the established Hollywood model, so in that sense they are all against the mainstream in one sense or another. At least that was the line I took in the book – looking at the different ways in which these films represent some kind of “cultural critique,” even when they’re not overtly political. And then there is a chapter on explicitly political films, which are mostly documentaries. One aspect of the book that is important to me is including documentaries within the general category of “independent film,” because that’s what they are. They are almost never looked at as part of the independent spectrum, but if you consider independent film in general as a critical genre, then documentaries are clearly at one end of the spectrum.

AOTC: Were you focused on this issue when you started the project?

SO: I had no idea of this when I started, and I had no idea that working with independent filmmakers per se would be so productive. And don’t we all everyday thank our lucky stars for the one rule of ethnography, which is: whatever happens! Whatever happens, that’s it. Don’t go in with too much agenda. Just be so open to whatever happens – it’s the cardinal rule and it works every time.

AOTC: So, what are you doing now?

SO: My new project grows out of the issues we were just talking about. I’m doing research on a production company that produces films that have some kind of progressive social agenda. It’s called Participant Media. They wouldn’t use the word “political” either, but anyway they make films that raise critical social issues. So this company invests in the films at the front end, and then they build what they call a social action campaign at the other end. They build these social action campaigns in cooperation with NGO’s. I’ve been interviewing people inside the company, and I’ve also chosen three of their films to look at in depth: “A Place at the Table,” a documentary about hunger in America; “Last Call at the Oasis”, a documentary about the water crisis; and an action film called “Snitch” that raises the issue of unjust sentencing laws in the war on drugs. I interviewed the filmmakers of those films, and also some of the NGO people Participant has worked with – hunger NGO’s, water NGO’s, several NGO’s involved in changing mandatory minimum sentencing laws. I was in Washington DC last week during the AAA meetings and doing these NGO interviews. It is absolutely fascinating.

- [1]Sherry B. Ortner (2014), “Too soon for post-feminism: the ongoing life of patriarchy in neoliberal America”, History and anthropology 25(4):530-549.↩

- [2]North Country (2005), directed by Niki Caro.↩

- [3]The Invisible War (2012), directed by Kirby Dick.↩

- [4]Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), directed by Alex Gibney.↩

- [5]Sherry B. Ortner (2013), Not Hollywood: Independent Film at the Twilight of the American Dream.↩

- [6]Sherry B. Ortner (1978), Sherpas Through Their Rituals.↩

- [7]Sherry B. Ortner (1989), High Religion: A Cultural and Political History of Sherpa Buddhism.↩

- [8]Sherry B. Ortner (1999), Life and Death on Mt. Everest: Sherpas and Himalayan Mountaineering.↩

- [9]Sherry B. Ortner (2003), New Jersey Dreaming: Capital, Culture, and the Class of ’58.↩

- [10]Hortense Powdermaker (1950), Hollywood the Dream Factory.↩

Please join our mailing list to receive notification of new issues