Old and new moralities in changing China

Yunxiang Yan

[Editors note: Yunxiang Yan was interviewed by Charles Stafford at the London School of Economics on December 2nd, 2014.]

AOTC: I’d like to start with a question about Mao, and about Maoism. As you know, when people talk about a moral crisis in China today, they often have the idea that the problem is Mao. That is, Maoism came along and devastated China’s traditional moral values and practices, leaving only confusion in its wake. But Maoism itself came from a moral standpoint. Mao himself, but also many ordinary people who got caught up in various activities in the revolutionary era, felt that far from doing something bad they were doing something good. And that even extends to the Cultural Revolution: many people felt that it was indeed moral to destroy Chinese traditions on the basis that these traditions had had very negative consequences for China. So could I ask you to reflect, from the position of today, on the question of the morality of Maoism?

Yan: I think there are two closely related issues here. One is about whether there was a Maoist morality. The other is about whether there is indeed a moral crisis in China today. To me, the second one is very debatable. If you were asking me around seven years ago, the answer would have been yes. Actually, this is one benefit of dragging out my manuscript writing over so many years, i.e. it’s probably good it’s taking me a very long time to finish my book about Chinese morality. My ideas keep changing. If I had finished the book five or so years ago it might have been yet another book entitled The Ugly Chinese. But now it’s something completely different.

Now I would argue that there has never been a moral crisis in China, truly. But if we mean a Chinese perception that there is a moral crisis, this started in the early 1980s. That is when a nation-wide debate started concerning the meaning of life. And then for around thirty years this so-called crisis has been revealing itself and has been discussed in various ways. But the specific content of the crisis has obviously changed very significantly – basically, every five years. So the question would be: which one is “the” crisis? Looking over the long run, I would argue that this is a moral transition, and that the prolonged process of this is still unfolding. And what this process means depends entirely on your perspective. At one moment you could feel that there is in fact a crisis. At another moment you could feel that this is about something important that is being renewed and that something inspiring could come actually out of this, in the end. It depends both on your temporal position and, more importantly, on an individual’s own moral perspective.

I think the very nature of this moral transformation is towards diversification of the moral landscape in China. This, in turn, is a reflection of how diverse the social landscape has become: which is a kind of social progress, of course. If you look at it that way, it’s a moral achievement rather than a crisis. But if we put it that way, and then ask about whether there was a Maoist morality, I think the answer is – first of all – a very firm yes. There was a Maoist moral tradition which, I would argue, is very much in line with Confucian ethics, very much in line with the long-standing moral tradition in Chinese society going back 2000 years. Obviously, the Maoist tradition claimed itself as revolutionary in attacking Confucian ethics. But the basic departure point and the ultimate goal were the same. That is, they both look at morality from a collectivist perspective and then use morality to require individuals to sacrifice two things – both of which, by the way, are critically important in the 21st century. The first is desire and the second is dignity.

In order to build a brave new world, most individuals need to sacrifice their individual desires. And in the heyday of Maoism probably everybody, including Mao himself, would think of themselves as making great sacrifices for this beautiful new world – a communist paradise. But that is actually very much in line with Confucian ethics. It is for the future goodness of the entire collectivity that everybody should curb his or her desires. Of course, there’s a return. The return is delayed gratification. If you keep cultivating yourself you will be, even in the old Confucian tradition, officially recognised in the end: perhaps by the imperial court, but even more importantly by the moral community where you live. And also you will be able to produce more descendents and thus a longer descent line: people still thought that your moral merit would eventually contribute back to the prosperity of your descent group as a whole.

AOTC: And what about the “dignity” side of this? Your point about desire I understand, but what about dignity?

Yan: In relation to dignity: as you know, there’s the Chinese idea of the self being divided. Every person is also simultaneously part of a bigger whole. So, in Confucian ethics a person is on the one hand part of a bigger kinship group, and on the other hand the subject of the emperor. So the two most important virtues – filial piety and loyalty – require you to submit your individual dignity to a much higher order. That’s what I mean. So when we come back to China’s current moral transformation the focus is precisely on desire and dignity. It’s about the legitimisation of individual desire, and about the pursuit of individual dignity. And these things are in contradiction to traditional Confucian ethics but also to Maoist ethics. So if we look at what’s happening from the collective perspective, then it is indeed a crisis in the sense that there is no hope to go back.

AOTC: With reference to Maoism in particular, what do you say to the argument that it was all cynical.

Yan: Cynical back then or now?

AOTC: Both, if you like, but perhaps thinking back, e.g. in your childhood.

Yan: I think in the 50s and 60s, up until the late 70s, cynicism was a relatively rare thing in China. I’m not saying that nobody was clear-headed and cynical, but there were relatively few such people and they wouldn’t dare to let others know their true thinking. So overall it was a very sincere time. And that’s an interesting thing about the current nostalgic reflection on Maoist times: it’s not so much on the specific content of Maoism but actually on the sincerity of Maoism back then.

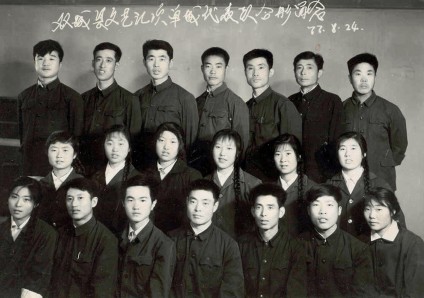

The Xiajia village performance troupe, 1972, after a gala show at the county seat; Yunxiang Yan is third from left, front row.

AOTC: Would you accept the argument that Chinese traditional moral values have, in various respects, been very exploitative, damaging, etc.?

Yan: It’s hard to answer that in a simple way. On one level, if I were to use the standard of individual desire and dignity the answer is yes, because Confucian ethics were built on the need to sacrifice the individual for the sake of the collectivity. Therefore from the individual point of view it is exploitative. However, even in that perspective there is this issue of temporality. The individual would eventually have the opportunity to have the upper hand and the whole system is designed to be beneficial to those who – eventually – are in that higher position. So it’s delayed gratification. If you live long enough, if you fulfill all your obligations, you become the family head. And women become the honoured grandmothers of a successfully run household. And so for you it’s no longer exploitative. It’s protective, it gives the older people a lot of privileges. So if you read novels from the May 4th era, e.g. by Ba Jin: twenty years later the younger generation would be in the same position as their fathers and grandfathers. Enjoying the system. So it’s not exploitative in that way but it is exploitative if you think equality of all individuals at any given moment is morally justifiable and even desirable.

AOTC: To switch to a different topic, in your earlier work – and especially in Private life under socialism – you show that in the post 1949 decades we find a decline of patriarchy, a decline of parental power, as a consequence of the revolution and all that went with it. But in some of your recent work you’re writing, in a way, about the opposite phenomenon: about Chinese parents really coming back into a position of power and being heavily involved in such things as divorce cases, in arguments about the custody of children, etc. So not only are these parents of adult children involved, they are actually powerful in terms of their influence. How would you explain this phenomenon?

Yan: That’s an important issue – one that I’m very interested in now, and it has indeed sidetracked me from my main focus on China’s moral transformation! But I consider it part of the same thing. I wrote two articles and I’m still basically making the same argument, which is that this is part and parcel of the same process of Chinese individualization. If you look at individual desire and dignity as the key measurement, the return of parental power is still about that: it’s all about them helping the younger generations – their children in these cases – pursue individual desire and dignity. And then there’s necessarily a negotiation across generational lines. The younger generation, mostly people born after 1980, get involved in these intergenerational negotiations and they reach a kind of compromise with the elders. The focus is still on the individual desires and dignity of the younger generation. But the older generation’s wellbeing – beyond economic consideration – is in fact very much tied up, it seems, with their adult children’s happiness. So the children do not feel any sense of shame in taking advantage of their parents, as it were, because they make their parents happy and in that way fulfill filial piety! This point was made to me by many young people I interviewed. Actually I think this may be a global trend: that the youth globally got softer, and no longer think of having a youth culture that is focused on rebellion against their elders. The younger generation in the US is heavily reliant on parental support, in fact, and there is much less dispute, and the disputes are mostly about minor things. There is no longer an ideological difference across generational lines. We are all living under this global consumerist ideology: we share so much in common that age no longer sets us apart. There are no social aspirations important enough to make the younger generation break from their parents, to build a new society. This is one level. Another level of this is that in the past a lot of the generational gap was about lifestyle. The younger generation wants to dye its hair blue, for example, and in the past something like this was serious – parents wouldn’t tolerate it. But now the diversification of lifestyles has become such an accepted thing that it is just part of daily practice. This reduces the possibility of a generational gap, globally.

AOTC: But even accepting what you say about this as a global phenomenon, I think many readers of your recent articles, for example about divorce proceedings in China would think – well, this kind of thing could never happen in, say, America. For example, the parents are in the court case sorting out what ought to happen with the children of their children – who themselves are simply sitting at the back of the court saying nothing. What is going on there? It does seem surprising, and especially in a place like China where we thought that the “elders” had lost all their power.

Yan: This question helps push my thinking into a different level. To put it in a nutshell, the key issue here is having or not having liberal individualism. This makes a huge difference. In the American case, individualism is under the skin. No matter if you like it or not, you just are that kind of person. It’s the predominant value and you need to live up to it, or at least be constrained by it. But as I’ve argued in my other work, the Chinese individualization process has not involved much liberal individualism so far. The decision to be made about a divorce is, in the American perspective, fundamentally concerned with a person’s individual dignity. In the Chinese cases I’ve studied it could all be interpreted – indeed was interpreted – very differently, as “my parents are acting on my behalf, for my interests”. Which of course is part of Chinese renqing culture: it’s fully legitimate for you to interfere in somebody else’s private affair, as long as it’s meant to be good for that person. And then you actually should proactively do that.

AOTC: I want to ask about two different points I’ve heard you make about recent anthropological work on morality and ethics. Point number one is that too much is said about “freedom”, in your view. Point number two is that not enough is said about immorality. Could you discuss these two points?

Yan: I think on the first point, the question is whether there are still bottom line moral principles that people in the whole society cannot go beyond. Scholars in the new anthropology of morality – including Zigon and Laidlaw, and to some extent Lambek – have wanted to ask questions about individual agency, even freedom. This is not only a difference in theoretical perspective, by the way, I think it is also something to do with fieldwork. Increasingly, our method of ethnography has been adopted by other disciplines and along the way I think anthropologists have, to some extent, lost their basic understanding about how to do ethnography. It is common now for anthropologists just to do interviews. Malinowski advised anthropologists not to ask questions, at least not in the first months of fieldwork, because you will be misled. This is well grounded. You need to have your own observations first before you interview people. Participant observation is thus more important than anything, otherwise we would have nothing distinctively anthropological to offer.

On the question of freedom: when we do interviews about morality people will give us moral reasons. But if we keep focusing on moral reasoning what we get is the individual’s after-the-fact reflection on, and justification for, what he has done. Of course, it makes sense! If I’m a drug addict, and if you ask me why have you gone this way in your life, I will give you a number of reasons that are predictable: I was made a victim by society, or this was an individually chosen lifestyle, and so on. But if you conduct participant observation at the same time you learn very different things. This is why I argue for the reconsideration by anthropologists of moral sentiment and moral instinct: things that basically cannot be gathered from interviews.

AOTC: So you’re arguing that the stress on freedom may come, in part, from an over-emphasis on interviewing people and a focus on the explicit moral reasoning that they engage in. Whereas if you observe moral life as it unfolds you might come up with a very different picture about how “free” in fact people are.

Yan: Yes. Of course, if we look at it from a developmental perspective freedom and individual choice are certainly very important. My stress on individual choice and desire in modern China is all about that. But I still insist that there are certain moral principles without which there is no morality. To deny this would be an extreme version of moral relativism – not just at the cultural level, at the individual level. For example, one thing I’m interested in now is the moral dilemma of gay people in China, who are forced to marry and have children. The dilemma is multi-faceted. They feel they are morally wrong when they cheat virtually all of the people involved: their parents, their spouse, their lover. And yet cheating in this case is the only way to be moral. To be moral you have to be immoral. If freedom is not a new virtue this would not be an issue. Only when freedom becomes available does this become an issue.

AOTC: So, what about immorality?

Yan: I made the point always in my research to simply follow my informants. You do fieldwork by participating in their lives, following them around, and what they definitely complain about, in my experience, is immoral behaviour. Which is understandable because morality is such an integrated part of everyday life – and when immoral behaviour occurs it is striking. So: why do scholars not pay attention to this issue? At first I thought it might be political correctness. As anthropologists, we are taught to be the representatives of the underdogs, meaning ordinary people. How can these ordinary people do morally wrong things? Maybe we are just seeing it from the wrong perspective. This is especially true when anthropologists study a culture that is not their own: they don’t feel they can be critical. So I may enjoy a privilege in being Chinese and writing about China. I can be the bad guy. Interestingly, early on I proposed to write a book chapter on food – and I was going to write about food safety issues in America and everybody claiming they are not responsible for them. So I was going to blame everybody! We want the best food, at the best price, in the most convenient form possible: so of course you get chemicals and bad things being added in by producers. We desire, we want the bad things, basically. It is part of consumer individualism. But then I was stopped by senior scholars who said: this is no good. I was attacking the American people actually. So I decided, ok. I’m a very practical Chinese. Maybe 10 years down the road I can do this. I need to make myself stronger to convince other people that I can say something about America.

AOTC: But going back to the point about immorality and China’s moral crisis. When you say we should be focusing on immorality you’re still not saying there’s a crisis per se, but there is a lot of immorality around, no?

Yan: I can see that it sounds contradictory. On the one hand, I’m saying there isn’t a moral crisis in China, just a transformation. On the other hand, many of the things I publish are about moral crisis in general and, often, about immorality in particular. Actually, in the book there are three things that I want to cover: ethics; contested morality – such as the case I mentioned about the marriage dilemma among gay people; and then new morality, representing to a certain extent universal values where the equality of humanity as a whole is at the centre. In China you have bad things happening, of course, but you also have good things happening, and something in the middle happening too. And some things are contestable and will be contested forever. Sex, for example. How much is good enough? How much is a little too much? It entirely depends on the eyes of the beholder – it will be contested.

But there are some things that I hope will eventually be accepted in China, e.g. greater empathy for others. This is what I call new morality. Let’s say an individual needs bone marrow transplant and then you have a flood of individual donations coming in. This is empathy directed at a total stranger and you won’t get any recognition and reward for it. It would not happen in China thirty years ago. Thirty years ago, in the height of Maoism, people would think: is this person a good or bad class label? If it’s one of us, we help them. If it’s a class enemy, we let them die. But now there’s an abstract notion of an individual in distress who needs help. This will continue to develop in China, it’s part of the new morality.

So I write about immorality partly because, first, it’s part of the whole picture. Second, it’s not written about that much in Western or Chinese scholarship. I looked on Chinese databases. In fact, only news reporters focus on this: scholars shy away from it. I can understand, because they don’t get sponsorship to do this and it might be politically sensitive. So I feel a greater responsibility since I am not part of this system. I can be more reflective.

One chapter I’m writing for the book is about why so many good people turn out to be corrupt when they become officials. When this chapter comes out I will be condemned, because actually I am defending the corrupt officials from a cultural perspective. In the sense that if you want to do anything good for your community, for your department, you have to follow the rules – and the rules have to be supported by certain practices that lubricate the mechanisms. And also, of course, you received help in the process of moving up the ladder, from so many people. You owe so much debt to so many people and now you need to pay it back. In the online discussions in China people have already noticed this phenomenon Fewer high-ranking officials who are princelings – i.e. children of the elite – fall down because of corruption. They themselves say: we don’t need it, we are less corrupt. Which is half true. If you look at the wealth accumulation efforts of these people, of course there’s a lot more wealth than you find with ordinary people. But they don’t have to go to the extremes of somebody coming out of a poor village who becomes an important official. For some people everything comes automatically. For somebody like Liu Zhijun, former minister of railways, he had to do a lot of extra things.[1] He had to be super hard working, and then to convince his superiors to promote him – which necessitates sending money out. It’s part of the Chinese renqing culture. I might make the argument that as long as the renqing culture is there, there’s no way to stop corruption. But if we stop renqing culture we stop being Chinese!

- [1]Liu Zhijun, known in China as “the father of high-speed rail”, was sentenced to death with a two-year suspension on corruption charges.↩

Please join our mailing list to receive notification of new issues