The Blob

Maurice Bloch

The history of the social sciences and especially that of modern anthropology has been dominated by a recurrent controversy about what kind of phenomena people are.[1] On the one hand there are those who assume that human beings are a straightforward matter: they are beings driven by easily understood desires directed towards an empirically obvious world. The prototypical examples of such theoreticians are Adam Smith, Herbert Spencer, or more recently the proponents of rational choice theory. The positions of these thinkers have been, again and again, criticised by those who have stressed that there can be no place in theory for actors who are simply imagined as “generic human beings” since people are always the specific product of their particular and unique location in the social, the historical and the cultural process. Among the writers who have made this kind of point are such as Emile Durkheim, Louis Dumont, and more recently Michel Foucault and the post-modernists.

Anthropologists have tended to be on the side of the latter since they like to use their knowledge of exotic societies to argue that what the others see as “human nature” is merely the western person glorified. Such a point is justified, but the culturalists rarely go on to answer the very difficult questions which would follow from it. How far do they want their argument to go? Is there really nothing to be said about the species Homo Sapiens?

The universalists criticise the culturalists by stressing the general aspects of such things as human cognitive development but then normally only pay lip service to the very difficult questions that cultural and historical variation pose for them. They are often joined, by implication at least, by cognitive scientists such as psychologists and analytic philosophers. This is so sometimes because of an argued commitment to the universalist notion of a maximising individual, such as is the case for the proponents of the Machiavellian mind, but, more often, simply by default.

The back and forth between these two ways of specifying human beings is in the end tiresome. The theoretical history of the social sciences has repeated itself far too often. We seem never to get anywhere since both sides seem to have good reasons for arguing that the other side is wrong without being able to incorporate the aspects of their opponents’ arguments which they usually also recognise, if only in passing, as valid.

The reason for this continual repetition of old controversies is the ease with which both sides can criticise the unreality of their opponents’ understanding of people. The culturalists point to the abstraction of disembodied a priori entities such as the rational actor of game theory, or the culture and history free creatures found in much of psychology. The universalists ridicule the equally bodiless and mindless creatures found in much of cultural anthropology where people are seen as nothing other than epiphenomena of specific cultures and localities.

In this article I want to argue that the cause for the endless repetition of controversy, in the social sciences at least, comes from our failure to consider people as natural organisms rather than as the abstractions of unclear ontological status that characterise social science theory. If we focus on the evolved human animal – a very special being that is not, however, ontologically different from other living species – we can begin to understand the complex way in which we are created simultaneously by our biology, which includes our psychology, and by history and culture. And we can do so without getting lost in the smoke of battle of the phantasy wars of social science theory.

Furthermore, if we do this we can think together with the other cognitive sciences and explain to them in a more convincing way how much they need to seriously take into account the social and the cultural.

***

My purpose in this article is to change the ground over which the old controversies have been fought to a manageable one where the different disciplines can meet to engage in a joint, yet difficult, enterprise.

Here I concentrate on the topic over which the apparently irresoluble conflict between the universalists and the culturalists seems most intense. The phenomenon I refer to is indicated by terms such as self, the I, agent, subject, person, individual, dividuals, identity, etc. These terms all involve the attempt to describe what it is to be oneself or somebody else, in this or that place. (Indeed, we may already note here that the problematic distinction between self understanding and the representation of others is usually unexamined in most of the social science literature, by way of contrast with its treatment in cognitive science.)

My lumping together of these different terms may well seem to be inappropriate, even sloppy, since many social science authors take great pain in distinguishing these words and in offering extremely precise definitions. The problem, however, comes when we try to put together this massive literature – when, for example, we try to relate Geertz’s discussion of the Balinese “person” (1973), with Dumont’s “individual” (1983), Mauss’s “moi” (1938) and Rosaldo’s “self (1984).[2] When I try this I have to admit that I am completely lost and so you will have to excuse me if I refer to this entire indistinct galaxy, some part of which, or all of which, these terms appear to refer to, simply as the BLOB. This seems particularly justified since in spite of this multiplicity of would-be distinct labels much the same claims have been made, whatever word is used.

When made by anthropologists, foremost among these claims is that the blob is fundamentally culturally and/or historically variable. This is what anthropologists mean when they say that there is no such thing as human nature, a proposition which poses the general epistemological problem of what then we are dealing with. Is the blob just an arbitrary category of culture, one that groups under various ethnocentric labels things that have nothing essentially to do with each other? If so, the blob, under whatever labels it masquerades, cannot be a suitable subject for theoretical study.

This possibility, however, seems not to be taken very seriously by anthropologists in spite of their general predilection for radical cultural determinism. When they actually get down to specifics we usually find much less ambitious propositions. It is not usually proposed that there are as many blobs as there are cultural variations but rather that there are two kinds of blobs in the world. Sometimes this point is expressed generally as a contrast between the modern or western blob and the blob of the rest of mankind. This is, for example, what Durkheim argued in The Division of Labour in Society with his distinction between organic and mechanical solidarity.

Similarly Dumont (1983) stresses the same familiar dualist contrast of the individualism of the post reformation West with the holism of the hierarchical rest. The same dichotomy is also found in the work of ethnographers or historians who, although they talk about particular places, argue that there, or then, the self, the person, the subject, or what have you, is different from what we, the modern west, have here and/or now. Thus Wood (2008) argues that the very notion of self was absent in biblical times, Snell argues the same of the Iliad (1953), Marilyn Strathern argues that the New Guinea person is quite different to the Western one (1988), Kondo argues this for the Japanese self (1990), Marriott for India (1977), Geertz for Bali (1973), etc. The west seems simply to be used as the contrast to the specific situations discussed, but, in fact, it turns out that these varied non-western non-modern places are very similar among themselves. That is, they are places where interiority and individuality is devalued and where social relationships and group membership dominate. More recently a further twist has been added with some writers arguing that in post-modernity we have now arrived at a post-blob, post-modern, stage (Ewing 1990, Markus and Kitiyama 1991). This addition might be thought to lead to a tripartite division with pre blob, blob and post blob, but in fact the proposed pre-modern blob and the post-modern blob look singularly alike in that they are both non-essentialist, distributed, contextual and divided. Anthropological arguments about the blob can therefore be summarised as saying there is a great and absolute divide between the individualist west and the social relational rest.

The basis for such repeated exhortation, that we should not assume, as the univeralists do, that what we know as the blob is applicable everywhere is real enough. It is a common experience of ethnographers who work in very different societies and cultural milieus, such as me to go no further, to be struck, and indeed even sometimes shocked, by how little value is given to individual motivations and how roles and group membership are the main, and often the only expressed, criteria of right conduct. This is also reflected in certain non modern, non western legal codes such as those on which Mauss based himself in his discussion of the concept of the person, or in rituals, such as those discussed by Marilyn Strathern which she uses as the basis of her analysis of the Melanesian dividuals (Strathern 1988). Such data does seem to produce a view of people as merely points in social systems while their internal states, their intentions, their absolute individuality and personal desires are irrelevant. This dichotomous contrast between the west and these “other” societies is often exaggerated (Béteille 1991, Lienhardt 1985, Parry 1989). However, there are very real and important differences between cultures which are worth discussing. Thus, it is not my intention to minimise the significance of the cultural argued for in the works I have been implicitly or explicitly referring to, but instead to ask whether the facts that have been noted have the fundamental implications for the “construction” of the blob that so many social scientists give them. I shall argue that they do not but then, by integrating the work of anthropologists with that of cognitive scientists, I want to place the anthropological ideas within a model that is not antagonistic, but compatible, with what cognitive sciences can teach us.

Two anthropological writers have already called into question the excesses of the relativist position in relation to the blob, especially when it goes under the name of “self”. Melford Spiro in a devastating critique of authors such as Marriott, Geertz and others demonstrates how the evidence used for such dramatic generalisations is selective (1993). As an example, he notes that reference to the devaluation of the self in Therevada Buddhism is not, as has been suggested, evidence of the absence of the notion in a country such as Burma, but rather, of its presence. In a somewhat similar vein Naomi Quinn (2006) criticizes recent post-modern writing in anthropology which suggests that the idea of the integrated self is outdated and/or wrong on the weak and trivial basis of the uncontroversial fact that people can hold contradictory ideas. Her point is that explicit reflexive self representation cannot be equated with the blob as it is lived and, putting the words in her mouth that I will use below, that we must distinguish cognition and meta-representation, that is re-representations, in these cases public, about cognition (Sperber 2000). (I am, however, much more hesitant than she is, given our present state of knowledge, in identifying various aspects of selfhood directly with different types of functional or anatomical areas of the brain.)

Spiro and Quinn make two convincing and important criticisms of the work of anthropologists: firstly, they are right that anthropological writing about the blob is often spectacularly imprecise and, secondly, it is true that claims made in this area are commonly of very uncertain epistemological status. I also support explicitly Quinn’s implicit argument that the attempt at naturalising what is being talked about would help clear the fog (Quine 1969).

The implication of the critiques by Spiro and Quinn is that anthropologists are wrong when they make the absolutist claim that the blob is simply a product of history and is totally culturally variable. Neither author, however, claims that culture and society do not have an influence, but the question how, and how far this is so, cannot be advanced until the epistemological status of what is claimed is clarified. Thus, as both Spiro and Quinn recognise, it is not that anthropologists are talking about nothing in their discussions of self, person, agent, personality, identity, etc., but that what they are talking about, and how far they want to go, cannot be pinned down.

As Spiro and Quinn have done a good job in criticising much of the previous anthropological writing on this topic, this clears the way for a more positive attempt at replacing the anthropology within the wider theory they implicitly call for. What follows is such an attempt.

***

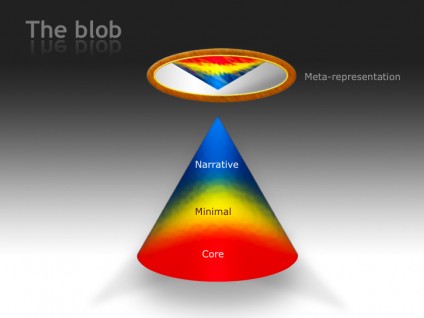

An obvious starting point is to distinguish levels in the phenomena to which the blob words seem to refer. It is true that some anthropological writers do make a weak attempt at distinguishing levels but these are soon forgotten. Thus Mauss begins his essay on the self and/or the person in the following way: “I [shall not] speak to you of psychology… It is plain…that there has never existed a human being who has not been aware, not only of his body, but also, at the same time of his individuality, both spiritual and physical… My subject is entirely different…the notion that men in different ages have formed of [the self]” (Mauss 1983: 3). Yet the essay continues as a discussion of his “first subject”. Similarly, though the other way around, Antze and Lambek state in a book about culture and memory that autobiographical memory “and the “self” or “subject” mutually imply one another” (Antze and Lambek 1996: xxi). But we then find that they slide away from a discussion of the central issue by telling us that “our book is less about memory than about “memory”… That is to say it is about how the very idea of memory comes into play in society and culture…” (p.xv). These are presumably local ethno-psychological theories about whose value they do not commit themselves. Mauss says that he will not talk of psychology but does, while Antze and Lambek declare they will but don’t and instead talk of what I shall call below meta-representations.

Distinguishing levels of the blob is very difficult but essential if we are to understand the relation of the blob to culture. Few things have more hindered dialogue between social and cognitive sciences than proper consideration of what level we are dealing with and of the significance of the relation between these levels.

What follows is, therefore, a rough attempt at distinguishing levels in the natural phenomenon because, I believe, this is necessary for understanding how social science, and especially anthropological, discussions concerning the blob can be integrated with those from the cognitive sciences. Interestingly, distinguishing levels also produces a kind of natural history of our species in that what I call the lower levels are characterised by features that we may assume are inherited from our very remote pre-mammalian ancestors since these are shared with other distant living species, while others, here qualified as higher, are unique specialisations of our species. The integration of anthropological considerations within the wider framework outlined here thus also suggests a facilitation of the integration of the social science theories within evolutionary theory (Seeley and Sturm 2006 p. 321ff).

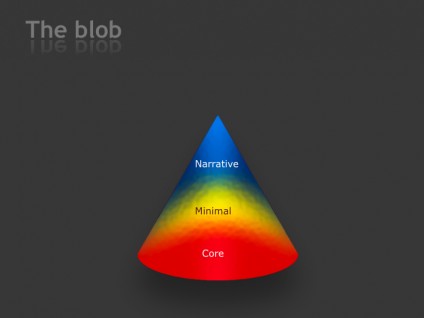

This preliminary attempt at distinguishing levels is based on the work of a number of scholars in cognitive science who tend to use one of the names of the blob: the self. Relying on these authors is, however, tricky since they are not all in agreement either. Fortunately, for the simple purposes of the present exercise, it is possible to by-pass the disagreements by concentrating on what most are agreed on. What is crucial is that there indeed are very different levels to the blob, with the deepest levels shared by all living things and the highest levels creating the possibility of a narrative reflexive autobiography. It is essential, however, to remember that all the levels one might choose to distinguish are simply points in what is a continuum, which means that they are all related to each other even though some are more directly culturally affected while others are not. All those involved in the discussions are agreed that somewhere in that progression language and reflexivity, meta-cognition or meta-representation, comes into play (e.g. Neisser 1988, Damasio 1999).

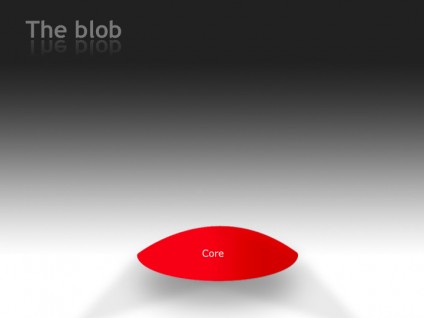

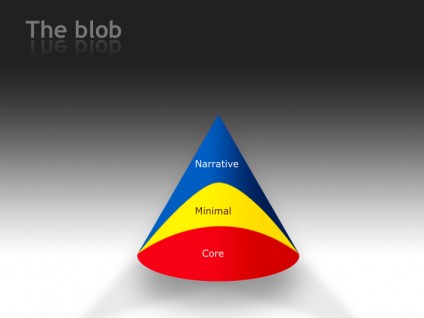

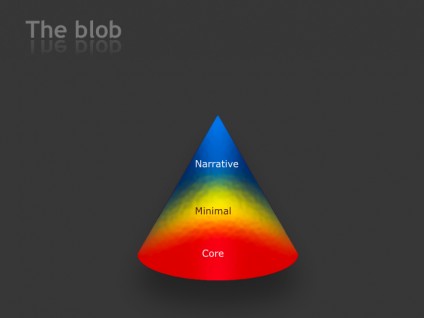

First of all we can distinguish a level that has often been labelled the “core self”.

Some aspects of this are very general indeed. These involve two things: 1) a sense of ownership and location of one’s body, 2) a sense that one is author of one’s own actions (David et al. 2008, Vogeley et al 2003). This type of selfhood must be shared by all animate creatures since, as Dennett puts it, even a lobster who relishes claws must know not to eat his own (Dennett 1995:429). (I suspect that even the most dedicated cultural relativist is unlikely to argue that this level varies from one human group to another.) It should be noted that the word “sense”, as I have applied it to this level, is used here in a particularly thin way, implying no reflexive awareness whatsoever. However it must also be stressed that, even at this level, we are dealing with quite complex cognition as Descartes’ discussion of phantom limbs long ago emphasised, and also as is shown by experiments, such as those where a subject can be made to feel sensations in a model arm (Botvinick and Cohen: 1998).

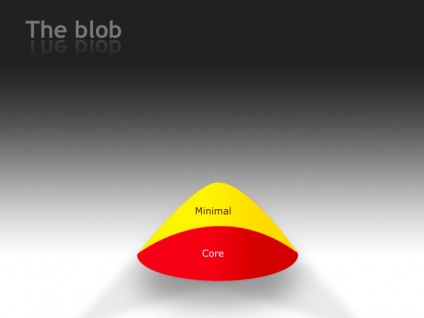

Above this level is one often labelled the “minimal self”.

This involves the sense of continuity in time. Many animals from crows to chimpanzees have this sense of their own continuity and they, like us, attribute a similar continuity in time to their con-specifics (Hauser et al. 1995). This sense of continuity in time is crucial for the use of any type of longer term memory and seems essential for more advanced cognition such as the ability of self recognition, demonstrated, for example, in recognising oneself in a mirror. Animals such as chimpanzees and gorillas can do this. Interestingly this sense of continuity of oneself and others is particularly developed in social species (Emery and Clayton 2004). Here again, when we are dealing with this level, the word sense is used in a thin way. It does, however, imply the ability to “time travel”, that is to use information about the past for present behaviour which involves being in the past in imagination, and the ability to plan future behaviour which requires being in the future in imagination. Nonetheless, it implies no reflexive awareness of the mental state that one is in. It involves the short term memory necessary to organise episodes, usually referred to as episodic memory (Conway 2001) and it involves the retention of some such episodic memories without these being woven into a coherent story, at least not one which is recoverable in consciousness.

Conscious access requires a higher stage which I call here, following a number of authors, “the narrative self” (Dennett 1992, Humphrey and Dennett 1989).

In some earlier writing autobiographical memory was practically synonymous with the self but this is clearly misleading if we remember levels such as those indicated by the terms “core self” and “minimal self”; the term “narrative self” was created to both maintain and limit the scope of the link. The narrative self and autobiographical memory imply each other (Tulving 1985). All humans create, at least after the age of three or four, such an autobiography though it remains an open question whether this is also done by other animals (Gallup 1970). The narrative self significantly involves reflexive interaction with others so that the self can become, in Mead’s words “an object to one’s self in virtue of one’s social relation to other individuals” (Mead 1962:172 cited in Zahavi 2010).

Before we go further I want to stress a point to which I shall return and which will become central for my argument. According to the model advanced here, the different levels of the blob are not fully separable. We are dealing instead with a continuum.

A number of difficult questions surround autobiographical memory and the narrative self – whether it need be conscious, how far it requires language, and how far it can be equated with the stories that people actually tell about themselves (Nelson 2003, Bloch 1998).

Some authors, such as Dennett and Ricoeur (1985), have argued that this level necessarily implies consciousness, language and the ability to tell stories about oneself, in other words explicitly expressed autobiographical memory. The difficulty with the notion of the “narrative self” comes precisely from this lumping together of different elements. Does the autobiography of autobiographical memory need be conscious or merely consciously accessible? Do autobiographical memory and the “narrative self” require language and, if not, is there not a non-linguistic narrative self, to be distinguished from a linguistic level? How far are we dealing with cognition or meta-cognition, with representations or meta-representations? In other words is having an autobiography the same thing as being aware that one has an autobiography? Is talking about one’s autobiographical past the same as having and using such an autobiographical memory, a capacity which, it is most likely, we share with non-linguistic anthropoids?

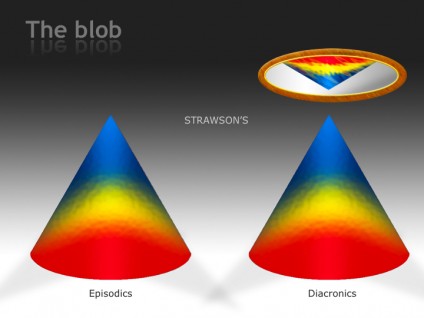

These difficulties have been highlighted by the philosopher Galen Strawson in his discussion of the notion of the “narrative self” (Strawson 2005). He argues that there are some people who are into creating conscious autobiographical narratives about themselves. These he refers to as “diachronics”. And there are others, like himself, who are just not interested in doing this. It is not their rhetorical style. He calls these latter people, somewhat unfortunately, “episodics”. Strawson intends the distinction to apply to all cultures at all times but the people he uses as examples are all Europeans or North Americans. As will be made clear below, although I am sure he is right that everywhere and at all times there are individuals of both type, that does not mean that the distinction is not of use also in contrasting different cultural settings.

Strawson convinces me that one should indeed separate those who merely manifest an “episodic self”, which does not involve a conscious and explicit expression of the kind of autobiography that one would talk about in natural circumstances, from those who manifest a “diachronic” self who have a strong sense of having a narrative autobiographical self or an “I that is a mental presence now, was there in the past, and will be there in the future” and who, most likely, go on about it (Strawson 2005:68).

Strawson talks of two different types of people, but this is so at the phenomenological level only. However I would argue that, in terms of the constitution of the blob, both lots, in spite of different outward behaviour, have a narrative self. Only some people, Strawson’s diachronics, have an extra. They have a deep feeling of having a meaningful autobiography and are likely to engage in a particular form of activity which involves creating a meta-representational diachronic narrative self by talking about their feelings, their inner states and their autobiography.

If that is so, Strawson is suggesting an answer to the questions which often are muddled together. The stories that some people tell about themselves and even about the feelings which they seem to express or about the nature of selves in their cultures are a quite different matter to whether they have a narrative self or not. Everybody has the kind of thing that Dennett and many other writers call a narrative self, if that is understood to involve only the basic elements shared by episodics and diachronics; but some people, the diachronics, go in for meta-representing this either to themselves or in spoken narratives.

Others do not or do so much less. And as Zahavi puts it, “we shouldn’t make the mistake of confusing the reflective, narrative grasp of a life with the pre-reflective experiences that make up that life prior to the experiences being organised into a narrative” (Zahavi 2010:5).

The difference between Strawson’s two types of people is thus much less fundamental than the differences in levels that I have been discussing so far. Indeed the fact that diachronics go in for meta-representations of themselves may be considered as a quite different matter than the constitution of the blob. Explicit manifestations are public acts and as such are determined by the social and cultural context in which they occur. Thus, at the level of discourse, Strawson’s diachronics and episodics will appear very different in that they will sometimes talk about different things and possibly sometimes act in different ways but this does not mean that they belong to quasi different species. In fact the difference that anthropologists stress so dramatically may be little more than one of rhetorical style and is certainly not a difference in the nature of the blob.

***

And this is where I return to anthropology. At the beginning of this article I recounted how many anthropologists seem to argue that there are two different kinds of people in the world. What I believe they were talking about was something much less fundamental. They are distinguishing between the people who Strawson calls diachronics and those he calls episodics. This is a difference which I rephrase as between those people who have got into the habit of talking about their inner states and those who don’t. This is an interesting difference but it does not mean that mankind is divided into two quasi species as is implied in the works I criticise. A surface difference is taken as a difference in substance. What such a mistake leads to is well illustrated by Unni Wikan in her criticism of Geertz’s depiction of the Balinese self (Wikan 1990).

If we return to Mauss and Antze and Lambek we find that they were aware of the distinction between the Blob itself and Meta-representations of the Blob, but in spite of this they slide from one topic to another and in fact only talk of meta-representations when they wish to talk about the blob. Most anthropologists are vaguer and simply happily talk of meta-representations as though they were the blob.

In those societies where, for historical/cultural reasons, it is acceptable, even encouraged, to talk about internal states of mind, individual motivations and autobiography, there are many diachronics and these will often take centre stage. It should be noted however that, as they do this, they are not exposing their selves, their individuality, their personhood, their agency, to the harsh light of day. They are doing something quite different; they are telling stories about themselves to others, which should not be mistaken for the complex business of being oneself among others. What they are doing when they are being diachronics, and this is the implicit point of Quinn’s criticism of post modernists, is interpreting those few aspects of their blob that are easily available to their consciousness, and then re-representing them as best they can, in other words publically meta-representing them. This clearly reveals the error of the direct “representational” reading that anthropologists have made of such meta-representational activity, which has led them to consider discourse about the self and others to be what it is a representation of.

In societies where, in most contexts, such meta-representational talk about one’s internal states and motivations is thought inappropriate or even immoral, discourse will obviously not normally be psychologically oriented but will be much more about the rules of behaviour that should be followed in groups, roles, rights and duties and exchange systems. This is my experience among the more remote Malagasy groups I have studied.[3] Such emphasis does not mean that we have found an alternative self, different from the self of the west where the rhetorical emphasis is on individuality and interiority. It is simply that when anthropologists are in societies where the glorifying of diachronics does not take place, they concentrate on the discourse about relations and morality – which, in any case, is found in all societies. Quite misleadingly, they make this into a compatible, if alternative, blob, a kind of substitute concept of the person, or the individual, or the self or the agent, while in fact it is nothing of the sort. There is thus no basis for a contrast between two types of blob.

This is all the more so as, most likely, we are dealing with a statistical difference not a categorical one. If the people of modern England are, as Strawson suggests, divided between phenomenological diachronics and episodics it is likely that the relative proportions are affected by the culture of England not merely by individual dispositions. If that is the case, it is also likely that in other cultures, these proportions will be different. In my experience, talk about internal states and individual motivations does occur in Malagasy villages, although rarely. The individualist, self reflexive blob cultures of the west are merely those where a lot of people go in a lot for diachronic narratives while the “others” are ones where people are rarely tempted to go in for meta-representation of their internal feelings.

***

I have used Strawson’s distinction between episodics and diachronics to show that anthropology’s two kinds of people are nothing of the sort.

However, an unfortunate conclusion could be drawn from the above. It might appear at this point that what I have argued is that meta-representations of the blob are cultural and that the blob itself is natural. This might be a modification to their theory that some culturalists or universalists might not have too much difficulty in accepting. They could then say: let the different disciplines get on with their own thing, the anthropologist talk about public meta-representations and the cognitive scientists talk about the fundamental blob. This would be totally misleading.

Cognitive scientists and social scientists may have been talking of different things with the same words, but both really want to talk about the blob. Anthropologists often make it clear that they desire to say something about the blob itself, even though they are continually led astray by the easier accessibility of meta-representations. However if we become aware of this problem, which is also the source of the tiresome repetition of the debate in the social sciences, then a framework for a proper joint enterprise can be envisaged. This I attempt to outline schematically in the last part of this article.

***

First of all it is important to remember, again, the most significant fact that the levels of the blob I have distinguished are not separate or fully distinct. There is a continuum from the core self to the narrative self (Squire 1992).[4]

All levels interact. Thus the narrative self is continuous with the primate-wide requirements of the minimal self and the minimal self is continuous with the living-kind-wide requirements of the core self. Similarly the narrative self is continuous with the minimal self which will itself be affected by the core self. We are psychologically and physically one.

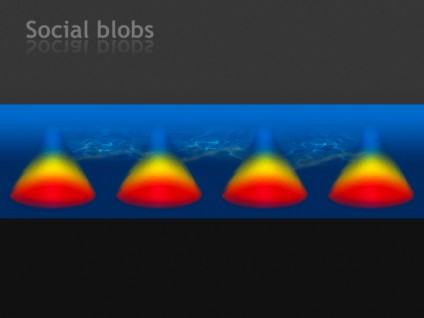

But there is also another aspect to the continuum of the blob. As we move to the higher levels, we also move from the internal and private level of such experiences as the awareness of ownership of one’s body and its location, towards the public, and therefore inevitably social, expressions of the narrative self.

This gradual move from the private to the public and, above all, its internal continuity are particularly important if we are to understand how the cultural/historical affects the blob. We might be tempted to assume that the private is untouched by the cultural while the public, caught up in social discourse, is entirely cultural. This would be misleading because it would forget the continuity of the blob through its various levels. The blob is a process. It is not a matter of a binary contrast but one of more or less. In other words, like icebergs, the blob is 90% submerged but the exposed part has no real independent existence from the submerged part and vice versa.

Moreover, to the internal continuity of the blob must be added another continuity: that between blobs. This I have not considered so far.

It is by means of the continual exchange between individuals that the cultural and, therefore, the historical character of the blob comes about (Sperber 1985, Dawkins 1976, Dennett 1995, Tomasello 1999).

Thus the analogy with icebergs can also mislead because, unlike icebergs, the exposed parts of the different blobs are not fully distinct one from another. They are organically united with each other. We are a social species and, as is the case for other social species, the fully isolated Cartesian individual cannot be anything other than what it was for Descartes – a thought experiment. It is through the continual complex social exchange between individuals which characterises our species, that history/culture becomes part of the process that is the blob. This is so because this interchange, in the case of humans, is part of a process which involves not only the interaction of presently living public parts of blobs but also the indirect inter-creation of the public parts of living blobs with the once public parts of dead blobs, in some cases public parts of blobs dead long ago.

The blob is not just situated in this process, it is itself moulded and modified by it to a significant degree. That the social and cultural character to a certain extent creates the blob has been stressed again and again in both the social science and the cognitive science literature, as it was in the remarks from Mead I quoted above. The social and communicative aspect of humans has meant that the boundary between the individual organism in a species such as our own is only partial in that we go in and out of each others bodies, not only because of the physiological processes of birth and sex but also through the neuro-psychological processes of the synchronisation of minds that occurs in social exchange. This I discussed in an earlier paper (Bloch 2007; see also Humphrey 2007).

This process of inter-penetration and historical creation is of course what social scientists and especially social and cultural anthropologists have traditionally emphasised. It is essential to any theory of the blob. The exposed parts of different blobs are to a varying extent continuous with each other. This applies not just to the levels of the narrative self but also to some aspects of lower levels captured by the term “minimal self”, since simpler but essential forms of joint action and therefore of interchange also exist. The merging of public parts of blobs is never complete since differentiation of one’s blob from that of others is as necessary for the social process as is the inter-penetration of different blobs.

This leads me to my very simple conclusion about the blob. The blob is simultaneously caught up in two quite different continuities both of which, at either of their poles, link what are essentially alien elements. One continuum links up, and to a certain extent merges, different but nonetheless distinct blobs, in other words, different people linked by social ties. The other continuum links the totally sub conscious core blob with the potentially re-represented narrative level. As is the case with the social link, elements that are ultimately different are partially united into a not fully integrated, or integratable, whole.

Thinking of either of these continuities is bad enough but we have to think of them together! If we do not, the difficult phenomenon we have to try to understand drains away with the bath water and we are left with concepts that cannot be related to anything in nature. The error of those cognitive scientists criticised by social scientists such as Durkheim is that they forgot the continuous social historical continuum and thus made mistakes that first year anthropology students have, as it were, explained to them again and again. We cannot talk of people in general without bearing in mind that they have been and are being made different to a certain extent by the social process.

Cognitive scientists have recently discussed extensively the mechanism which makes the cultural nature of humans possible. However, they have not taken on board the obvious implication of this: that because of culture there are no purely generic humans. The implications of this for research and more particularly cross cultural research are dramatic and rarely accepted. It is that whatever empirical work we want to carry out demands that we first understand our subjects in their unique specificity and not just as fully formed humans who are then superficially affected by culture.

The problem of the social scientists is double. First of all, there is the fact that I discussed already. On the whole, they have only looked at meta-representations of the blob and, occasionally, at the narrative level. This is because this is what their research methods made easily available. They then have either pretended that these levels were the total blob or they have argued that these levels were clearly distinct from other levels, thereby implicitly importing the kind of nature/culture dichotomy that, in another register, they denounce.

Secondly, when thinking about the blob they have forgotten its internal complexity. This is what I have been stressing here. They have forgotten that it seamlessly joins very different types of phenomena some of which, although inseparable, are totally unaffected by the mechanisms which they study.

***

I have tried to reconcile the kind of ideas that have characterised anthropological writing on the blob with those that are found in cognitive science. I have attempted to build a model which can include the theoretical points and observations that have come from both sides within a system where the different factors that have interested social and cognitive scientists affect different parts of a single natural phenomenon. This is because representations of the human blob have to be compatible with the multiplicity of empirically inseparable processes within which we exist. All living things are caught in two processes, phylogeny and ontogeny.[5] When we are dealing with our species we have to add a third process: that of history. This I have included and revised in the discussion of cultural interaction. We must keep, at least in the back of our minds, all three processes otherwise we are forgetting the specific nature of the human animal. Instead, we move into a hazy land, where nothing can be situated in nature, and where mysterious words, such as those which I have merged together to create the blob proliferate, without anyone being able to explain how they relate to each other. This, of course, is inevitable when we are in the never-never land of culture without minds and bodies or in the never-never land of minds and bodies without culture and history.

REFERENCES

Antze, P. and Lambek, M. 1996. Tense Past: Cultural Essays in Trauma and Memory. London: Routledge.

Béteille, A. 1991. Society and Politics in India: Essays in a Comparative Perspective. London: Athlone.

Bloch, M. 1998 Time, narratives and the multiplicity of representations of the past. In M. Bloch, How We Think They Think, pp.100-113. Boulder: Westview Press.

Bloch, M. 2005. Essays on Cultural Transmission. London: Berg.

Bloch, M. 2007. Durkhemian Anthropology and Religion: Going in and out of each other’s bodies. In H. Whitehouse and J. Laidlaw (eds), Religion, Anthropology and Cognitive Science. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Botvinick, M. and Cohen, J. 1998. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 391:756.

Conway, M. 2001. Sensory-Perceptual episodic memory and its context: Autobiographical Memory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Series B, pp.1375-1384.

Damasio, A. 1999. The Feeling of what Happens. London: Heineman.

David, N., Newen, A. and Vogeley, K. 2008. The “sense of agency” and its underlying cognitive and neural mechanisms. Consiousness and Cognition, 17(2):523-34.

Dawkins, R. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dennett, D. 1992. The Self as a Centre of Narrative Gravity. In F. Kessel, P. Cole and D. Johnson (eds.), Self and Consciousness: Multiple Perspectives. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Dennett, D. 1995. Darwin’s dangerous Idea. London: Penguin.

Dumont, L. 1983. Essais sur l’Individualisme. Paris: Seuil.

Durkheim, E. 1893. La Division du Travail Social. Paris: Felix Alcan.

Emery, N. and Clayton, N. 2004. The Mentality of Crows: Convergent Evolution of Intelligence in Corvids and Apes. Science 306(5703):1903-1907.

Ewing, K. 1990. The Illusion of Wholeness: Culture Self and the Experience of Inconsistency. Ethnos 18(3) 251-278.

Gallup, G. 1970. Chimpanzees: Self Recognition. Science 167, 86-87.

Geertz, C. 1973. The interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Hauser, M. et al. 1995. Self-recognition in primates: phylogeny and the salience of species-typical features. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 92(23):10811-10814.

Humphrey, N. 2007. The Society of Selves. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Series B, 362:745-754.

Humphrey, N. and Dennett, D. 1989. Speaking for Ourselves: An assessment of multiple personality disorder. Raritan 9(1): 68-98.

Knoblish, G. and Sebanz, N. 2009. Evolving intentions for Joint Action: from Entrainment to Joint Action. In C. Renfrew, C. Smith and L. Malfouris (eds.), The Sapient Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kondo, D. K. 1990. Crafting Selves. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Lienhardt, G. 1985. Self: public, private. Some African representations. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins and S. Lukes (eds.) The Category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Markus, H. & Kitiyama, S. 1991. Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion and Motivation. Psychological review 98(2) 224-253.

Marriott, M. & Inden, R. 1977. Towards an Ethnosociology Of South Indian Caste Systems. In D. Kenneth (ed,) The New Wind. Changing Identities in South Asia. The Hague: Mouton.

Mauss, M. 1938. Une Categorie de l’Esprit Humain: la notion de personne, celle du “moi”, Un plan de Travail. In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 68:263-281.

Mauss, M. 1983. A category of the human mind: the notion of the person; the notion of self. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins and S. Lukes (eds.) The Category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, C. and Lemmon, K. 2001. The self in time: Developmental perspectives. Hillsdale: Lawrence, Erlbaum Associates.

Neisser, U. 1988. Five Kinds of Self Knowledge. Philosophical Psychology 1:35-59.

Nelson, K. 2003 Narrative and Self, Myth and Memory: Emergence of the Cultural Self. In R. Fivush and C. Haden (eds.) Autobiographical Memory and the Construction of a Narrative Self. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Parry, J. 1989. The end of the Body. In M. Feher, R. Naddaff, and G. Tazi (eds.), Fragments for a History of the Human Body, Vol, 2. New York: Zone Books.

Snell, B. 1953. The Discovery of the Mind, trans. T. G. Rosenmeyer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Squire, L.R. 1992. Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with monkeys and humans. Psychological Reviews, 99(2), 195-231.

Quine, W. V. O. 1969. Epistemology naturalized. In Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 69-90.

Quinn, N. 2006. The Self. Anthropological Theory, 6(3):365-387.

Ricoeur, P. 1985. Temps et Recit. Vol.3. Paris: Seuil.

Rosaldo, M. 1984. Toward an anthropology of Self and Feeling. In R. Schweder & R. LeVine (eds.) Culture Theory: essays on mind, self, and emotion, pp.137-157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seeley, W. and Sturm, V. 2006 (2nd Ed.). Self representation and the frontal lobes. In B. Miller and J. Cummings (eds.), The Human Frontal Lobes. Guilford: The Guilford Press.

Sperber, D. 1985. Anthropology and psychology: Towards an epidemiology of representations. Man (N.S.) Vol. 20:73-89.

Sperber, D. 2000. Metarepresentations in an Evolutionary Perspective. In Metarepresentations: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spiro, M. 1993. Is the Western Conception of the Self “Peculiar” within the context of the World Cultures. Ethos 21(2): 107-153.

Strathern, M. 1988. The gender of the Gift. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Strawson, G. 2005. Against Narrativity. In G. Strawson (ed.), The Self? Oxford: Blackwell.

Tomasello, M.1999. The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tulving, E. 1985. Memory and Consciousness. Canadian Psychology, 26: 1-12.

Vogeley, K. and Fink, G. 2003. Neural Correlates of the First-person-perspective. Trends in Cognitive Science Jan 7 (1): 38-42.

Wikan, U. 1990. Managing Turbulent Hearts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wood, J. 2008. How Fiction Works. New York: Farrar.

Zahavi, D. 2010. Minimal Self and Narrative Self: A distinction in need of refinement. In T. Fuchs, H. Sattel and P. Henningsen (eds.), The Embodied Self: Dimensions, coherence and disorders. Stuttgartt: Schattauer Gmbh, pp.3-11.

- [1]I would like to thank the participants in the CNRS summer school on “Conscience de soi, conscience des autres” organised in Cargèse by Elisabeth Pacherie and Frédérique de Vignemont which inspired me in writing this paper, the members of the Culture and Cognition seminar of the LSE who made many useful comments on an earlier version, colleagues at the Free University of Amsterdam where I delivered an earlier version, and the philosophers Galen Strawson and Dan Zahavi for useful corrective comments. I also thank Veronica Holguin who provided the illustrations.↩

- [2]Andre Béteille expresses the same frustration (Béteille 1991:251).↩

- [3]Though it is also important to note that such talk about internal states can easily be generated as it can in England, thus showing that it exists in some contexts. This I have described in recent publications (including Bloch 2005).↩

- [4]Squire shows that the old distinction between declarative and non declarative memory is not neurologically based.↩

- [5]Our models must, therefore, talk of living things whose specificity, explicitly or implicitly, is comprehensible as the product of the process of natural selection. This is done here in that I have suggested something of the evolutionary history of the blob. These living things must be able to be produced and develop, grow from single cells to the mature phenomena we claim they are. I have not been able to touch on this here but I have used cognitive science literature which has begun to explore that side of things extensively (e.g. the studies in Moore and Lemmon: 2001).↩

Please join our mailing list to receive notification of new issues