Anthropology and anthropologists forty years on

Adam Kuper

I

My account of British social anthropology was first published by Penguin Books in 1973 under the title Anthropologists and Anthropology. It was not welcomed by the anthropological establishment, yet sold steadily for a number of years before falling below the level that was required in those days for a mass-market paperback. Ten years after its first publication it was reissued by Routledge. The title was changed – I don’t remember why – to Anthropology and Anthropologists, and I made some revisions, adding a more gloomy conclusion. A third revision, with a more upbeat conclusion, appeared a decade later. Since then three excellent biographies have appeared, of Malinowski, Edmund Leach and Mary Douglas, alongside a number of memoirs and interviews. Historians have dug into the archives and found surprises there. In the meantime some matters became clearer to me. On others I changed my views. Now, forty years after the book was first published I have undertaken a thorough revision, so radical that I was tempted to issue it under yet another title, but instead simply changed the sub-title (for the fourth time, as a matter of fact).[1]

Anthropology and Anthropologists is an ethnographic account of British social anthropologists in their golden age, the middle decades of the 20th century. What really matters is to be found in what they left behind: the books and papers and intellectual arguments that testify to what those men and women made of the world they lived in. Yet as anthropologists these particular natives knew very well that their academic work was shaped, among other things, by personal background, friendships and rivalries, career structures and institutions, and the politics of the times. An ethnography should explain all that, and I have tried to bring out the interplay between these various contexts and constraints.

As a participant observer, I was perhaps too close to the natives to keep them always in their proper perspective, although I have done my best. My dear aunt, Hilda Kuper, who first interested me in anthropology, was a student of Bronislaw Malinowski. Malinowski was a founding ancestor of the tribe, and I was used to hearing the pros and cons of his personality and his ideas, and those of A. R. Radcliffe-Brown, his great rival, being thrashed out by people who had studied under them.

Even in the early 1960s, when I was inducted into the tribe, British social anthropology was still a small community: there were seven departments and perhaps a hundred university teachers. The discipline was a new one, but it was rather traditionalist, with its taboos, its myths and rituals, and its rivalrous chiefs. Nevertheless new recruits who had passed through the initiation ceremony of fieldwork were made to feel that they were members of the clan. We all got to know one another, and I came to know some of the elders very well, over many years – Meyer Fortes, Isaac Schapera, Audrey Richards, Mary Douglas and Ernest Gellner were personal friends.

II

I fetched up in King’s College, Cambridge, in 1962, at the age of twenty, as a research student in social anthropology.[2] This was still very much the pre-modern Cambridge, and for a young foreigner it was exotic and more than a little unnerving. But the department of social anthropology presented special problems for the newcomer. It was small. There were only perhaps a dozen research students, of whom four or five would be away in the field at any one time. The academic staff was only seven or eight strong. It was, however, deeply divided.

The dominant figures were the Professor, Meyer Fortes, and the Reader, Edmund Leach. They were Big Men in the opposing factions of British social anthropology, the party of Malinowski and the party of Radcliffe-Brown. The new research student had to join one camp or the other. This had to do in part with where one wanted to work. In general, Fortes directed the Africanists, with the help of his lieutenant, Jack Goody, while anybody travelling East of Suez worked with Leach. (The rest of the world was divided up as convenient.) But this initial choice entailed an intellectual orientation as well. The Africanists were expected to work in the tradition of Radcliffe-Brown. The rest joined Leach in the Malinowskian camp. They were also, somewhat confusingly, introduced to the structuralist anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss, to which Leach was increasingly committed.

A university like Cambridge is an efficient engine of acculturation. The department itself impressed a very specific academic identity on the new recruit. Within a couple of terms it would turn out a fledging Fortesian Africanist or structuralist South Asianist, armed with some ideas but above all with strong loyalties. These convictions were inculcated with a minimum of direct instruction. One had to pick up a great deal on one’s own. We also all imbibed the faith that field research in the Malinowskian manner – by participant observation – would yield a more accurate view of another way of life than any other method. But how was it done? We put nervous questions to the faculty but were told that there was no fixed procedure, nothing that could be taught. The important things to bear in mind were that one had to remain healthy and on good terms with the authorities, and keep duplicates of field notes, sending copies home as often as possible.

That was the established tradition. The veterans boasted that they had gone into the field without any guidance or, at best, with risible and conflicting pieces of advice on matters of etiquette. The great ethnographer, Edward Evans-Pritchard, claimed that he was told by his supervisor Charles Seligman to keep his hands off the local girls, while Malinowski advised him to take a native mistress as soon as possible. And yet, of course, the directives were in their way explicit enough, perhaps all the more powerful for being purveyed through indirection and, especially, by way of personal anecdote.

III

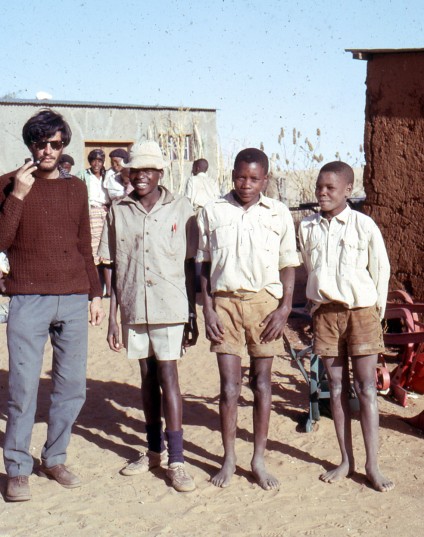

I missed the big bang of the late 1960s – I spent those years in Botswana and Uganda. In 1970, when I returned, it was to a profoundly changed British university world and to a discipline under threat. Hardly had I begun to get my bearings than Isaac Schapera invited me to write an account of modern British social anthropology. I had not for a moment contemplated such a project. He, no doubt had his reasons, never entirely clear to me. Anyway, young, heedless, and rather hard-up, I took it on, interviewed the more cooperative of the elders and organized a seminar series at which several of them were persuaded to reminisce.

News of the project drew a mixed response. Some senior colleagues were cautious, even furtive, readier to purvey unreliable anecdotes about their contemporaries than to talk openly about themselves. Two or three were deliberately obstructive. Yet I was not prepared for the reactions that publication provoked. It was, of course, a young man’s book, and the tone lacked reverence. This was, after all, the ‘Sixties’, still in full flow in the early 1970s. I appreciated that some might feel that it dealt too much in personalities. Here and there I had touched on matters that were still controversial. Nevertheless, I was astonished by the emotional response of some of the older generation. From Manchester, Max Gluckman engaged me in a furious correspondence. The dean of the profession, Sir Raymond Firth, made it clear that he was not amused. It was only after two decades that Lady Firth could draw me aside and tell me, ‘Raymond has forgiven you’. Young fogeys in the Oxford faction of social anthropology were even more splenetic. For the next two decades my book was virtually banned in Oxford and had to be read as samizdat.

In retrospect I can see that the emotional reaction had something to do with the fact that the book was published at a moment of transition in British social anthropology. Rivers was the leading British anthropologist in the early 20th century. He made several short-term field expeditions. Theoretically he drew on the evolutionism of the Victorians and later from the German geographical school. These approaches were rejected by the leaders of the next generation, Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown. Malinowski pioneered new methods of field research. Radcliffe-Brown introduced the sociological theory of Émile Durkheim. Radcliffe-Brown was Rivers’s first student in anthropology, and he was casting his arguments in the form of a critique of Rivers twenty years after his teacher had died. Bronislaw Malinowski worked in Melanesia, about which Rivers had written his masterpiece, and he once boasted that if Rivers had been the Rider Haggard of anthropology, he would be its Conrad. Together the two founding fathers established what amounted to a new tradition of intellectual enquiry, which came loosely to be called ‘functionalist anthropology’, or simply ‘British social anthropology’.

Surprisingly quickly, what had been a radical, fringe enterprise became mainstream. The students of Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown took up the research fellowships and university posts that now became available. After the Second World War they were appointed to the chairs in the various old and new departments in Britain and the Commonwealth, and they controlled the field for the next two decades. In the early 1970s, when my book appeared, the professors were all retiring. It was a touchy moment, particularly since, as the Belgian anthropologist Luc de Heusch perceptively observed, British social anthropology differed profoundly from its French counterpart by virtue of a remarkable trait: ‘elle a l’esprit de famille’.

Preparing the third edition I had recognised that my book was turning into something of an obituary notice. The project initiated by Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown underwent a crisis in the 1970s. A different social anthropology emerged in the post-colonial world. Research students who came into the discipline in the 1960s were influenced by structuralism and by the Marxist ideas of the period. They took note of changing fashions in American cultural anthropology, which was going through a transformation of its own. Some were especially influenced by feminist ideas. Others went into new sub-fields, notably medical anthropology, visual anthropology and cognitive anthropology.

‘Is it anthropology?’ conservatives grumbled, but, inexorably, the discourse of social anthropology was transformed in the last decades of the 20th century. Its most influential exponents in those years – Pierre Bourdieu, Mary Douglas, Ernest Gellner, Bruno Latour – were interdisciplinary figures. And no longer a specifically British or even Franco-British enterprise, the very nature of social anthropology changed fundamentally. It became a cosmopolitan project.

IV

Between 1924 and 1938 Malinowski’s seminar met weekly in term time at the London School of Economics. Here the next cohort of social anthropologists was formed. As late as 1939 there only some twenty professional social anthropologists in the British Commonwealth, and almost all had been regular participants in the famous seminar.

The participants in the seminar felt that they were engaged in a sort of game, Audrey Richards recalled, in which the aim was to discover ‘the necessity of the custom or institution under discussion to the individual, the group or the society’.

If the Trobriand islanders did it, or had it, it must be assumed to be a necessary thing for them to do or to have. Thus their sorcery, condemned by the missionary and the administrator, was shown to be a conservative force supporting their political and legal system. Pre-nuptial licence, also frowned upon by Europeans, was described as supporting marriage institutions and allowing for sex selection. The couvade was no longer a laughable eccentricity but a social mechanism for the public assumption of the father’s duties towards the child.[3]

The students continued the conversation informally among themselves through the week, meeting up in the Reading Room of the British Museum during the day and in pubs in the evening. As the first students went out into the field and returned, new findings were discussed, fresh problems raised. Theories were stretched, questioned, vindicated and, occasionally, relinquished, though seldom by Malinowski himself.

The first generation of Malinowski’s students were mature people, often with professional qualifications, some with experience in colonial government. They were prepared to stand up to Malinowski, and he enjoyed provoking them. Edward Evans-Pritchard was respected and treated with some apprehension (the Black Knight, the loyalists called him). Not so a nagging trio of nit-pickers, Meyer Fortes, Siegfried Nadel, and a Dutchman, Sjoerd Hofstra, whom Malinowski derisively dubbed the Mandarins. ‘Strong personal bonds developed between us and with Malinowski,’ Hortense Powdermaker recalled, ‘it was a sort of family with the usual ambivalences. The atmosphere was in the European tradition: a master and his students, some in accord and others in opposition.’[4]

A second cadre of students, who joined the seminar in the 1930s, were generally younger, and less inclined to challenge Malinowski, but they were more likely to have had an undergraduate training in the field, usually in South Africa or Australia. In 1930, Isaac Schapera taught for a year at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. His students included Max Gluckman, Ellen Hellman, Hilda (Beemer) Kuper and Eileen (Jensen) Krige. All of them went on to study with Malinowski and became professional anthropologists. There was a similar migration to London from the anthropology department at Sydney that had been established by Radcliffe-Brown.

V

Initially very little funding was available to send people into the field. Most of the first cohort of Malinowski’s students wrote their dissertations from secondary sources, recasting ethnographic reports on a region in a functionalist mode, as Malinowski himself had done with his study of the family among the Australian Aborigines. In 1931 Malinowski and the International African Institute launched a research fellowship programme funded by a Rockefeller family foundation. This supported seventeen of Malinowski’s students over the next five years. They went to Africa rather than Melanesia, and the discipline now began to focus on new issues – politics and law especially. Above all, the functionalist school was shaped, in ways that are only now perhaps becoming fully apparent, by the African colonial system. And there was a price to be paid for that.

Siegfried Nadel delivered a lecture on applied anthropology in London in 1955. Afterwards, he recalled, ‘a number of West African students in the audience violently attacked me, all my fellow workers in that field, and indeed the whole of anthropology. They accused us of playing into the hands of reactionary administrators and of lending the sanction of science to a policy meant to “keep the African down”.’ [5]

By the 1960s these sentiments were widely shared among African intellectuals. The charge was that anthropologists stigmatized Africans as primitive, sided with traditional rulers against the educated urban population, and generally did what they could to prop up colonial rule.

A more generalized critique emerged in the 1970s. Taking a lead from the writings of Edward Said, radical academics now denounced anthropology as an expression of the colonial mind-set that regarded colonial peoples as objects and constructed false and mystifying differences. It was damned as a branch of ‘Orientalism’, which Said characterized as ‘a kind of western projection onto and will to govern over the Orient’.[6]

British social anthropology was a particular target, since Malinowski’s school had engaged with the policy of Indirect Rule in Africa.[7] A series of case studies appeared that hit upon some confidential report, or cited rash promises made by academics in pursuit of funding, and denounced social anthropologists as spies and partners in colonial oppression.[8] Some of the older generation responded with rather defensive memoirs,[9] although even the best efforts of the critics could not turn up any particularly shocking instances, let alone a consistent pattern of collaboration.

A less judgmental approach was inspired by Michel Foucault’s paradigm of knowledge and power. The argument was made that anthropology and colonial rule developed a symbiotic relationship. Social anthropology could claim to be a practical science of primitive folk. Armed with this science, colonial governments could recast their rule as a project of benevolent social engineering. Anthropology should therefore be situated in the context of particular colonial projects. ‘What needs to be addressed,’ Benoît de L’Estoile remarks, ‘is precisely what is meant by anthropological knowledge being a “colonial science”. We need to understand the specific historical configuration in which some discourses and practices could be held as “scientific”, while at the same time unambiguously belonging to the colonial world.’[10]

British colonial policy in Africa began to change in the 1930s. The African colonies were stagnating economically. There was political unrest. In the UK, Labour politicians were challenging the colonial system. African nationalist movements were gaining ground, inspired by the example of the Congress movement in India. The Colonial Office began to press African colonial governments to draw up economic plans and to undertake administrative reforms. Joseph Oldham, a missionary politician and intellectual, who had set up the International African Institute, now persuaded the Laura Spelman Rockerfeller Memorial foundation to fund fellowships at the LSE for research on ‘applied anthropology’ in Africa. Malinowski was selected to train and supervise the research fellows. The upshot was that he cornered the market in applied anthropology in Britain’s African colonies, shutting out Seligman, the African expert at the LSE, and beating off competing bids, including one from Radcliffe-Brown, some of whose students in Sydney had been supported by Rockefeller grants.

Malinowski was ready. He had his own interests to promote, and above all, students to fund, but he also felt that there was an elective affinity between functionalist anthropology and the policy of Indirect Rule. In a paper entitled ‘Practical Anthropology’ published in 1929 in Africa, the journal of the International African Institute, Malinowski had called for ‘an anthropology of the changing native’. The proper ethnographic object was not ‘savage cultures’ but rather colonial cultures in a process of rapid change.

But despite Malinowski’s promises, the African Institute’s research fellows would do very little by way of applied anthropology. Audrey Richards had to admit that ‘the anthropologist often offers his help, but seldom condescends to give it.’[11] Or perhaps the demand just was not there. ‘It looks as though the anthropologist had been advertising his goods, often rather clamorously, in a market in which there was little demand for them’, she ruefully remarked.[12] The reality is that British anthropologists were little used by the colonial authorities, and, despite their rhetoric when in pursuit of funds, they were not particularly eager to be used.

One problem was that anthropologists were easily dismissed as romantic reactionaries who wanted to preserve ‘their tribe’ from any outside contacts, and to keep them as museum exhibits in splendid isolation from trade, government and Christianity. By the late 1930s the colonial governments were all committed to the extension of the cash economy, to the support of missions and mission education (with some local exceptions in Muslim areas), and to the establishment of new forms of law and government.

It could hardly be denied that some functionalist anthropologists did indeed deplore many of the changes that had occurred in Britain’s African colonies. Several leading figures were cultural conservatives. Malinowski certainly was, in his very particular fashion. With his roots in the anti-imperial nationalism of Central Europe, he was sympathetic to the cultural nationalism of his student Jomo Kenyatta. He wrote a glowing preface to Kenyatta’s ethnography, Facing Mount Kenya, and he later supported the tribal nationalism of the Swazi King, Sobhuza. Malinowski would claim that ‘speaking as a Pole, on behalf of the African, I can put my own experience as a “savage” from Eastern Europe side by side with the Kikuyu, Chagga or Bechwana.’[13]

Malinowski was never politically correct, but his position was very different from the frankly racist colonial orthodoxy, in thrall to stereotyped notions of African mentality, contemptuous of African civilisations. He was more in sympathy with a strand of liberal thinking on colonial policy in the 1920s and 1930s, which tended to regard change as dangerous. The premise was that cultures all have a value, which should be respected, and that tribal cultures are peculiarly vulnerable to corruption, even disintegration, on contact with outside forces. Therefore the forces of decency should be ranged against radical changes of any kind. Liberals warred particularly against the forces of change that had most obviously damaged African interests – white settlement, migrant labour, and so forth. Malinowski gave this view a functionalist twist. The native was being ‘forced to labour on products he did not wish to produce so that he might satisfy needs that he did not wish to satisfy.’[14]

Some cultural conservatives became advocates for the sectional interests of particular tribal elites. Others teamed up with progressive colonial officials: in Uganda, Audrey Richards worked closely with Sir Andrew Cohen, an enlightened Governor. But by no means all the social anthropologists were either conservatives or liberal imperialists. The Colonial Office was always on guard against radicals, communists and agitators who, it feared, were being slipped into the field by guileless professors back home.

There was also a counter-current within the small community of British social anthropologists, a principled resistance to applied research that began to be articulated in the late 1930s. In the conclusion to his Malinowskian monograph, We the Tikopia, published in 1936, Raymond Firth warned that science was ‘in danger of being caught up by practical interests and made to serve them, to the neglect of its own problems’. Social anthropology should be committed to understanding social groups ‘not with trying to make them behave in any particular way by assisting an administrative policy.’

Firth changed his tune when he landed a big role in the Colonial Social Science Research Council, but the purist line was asserted even more strongly in Oxford. In reaction to Malinowski’s monopoly of Rockefeller Funds, and his access to the Colonial Office, Evans-Pritchard denounced applied research and insisted that social anthropology should be a strictly academic pursuit. He took to referring to the LSE as the £.s.d., and in 1934 he wrote from Cairo to Meyer Fortes:

The racket here is very amusing. It would be more so if it were not disastrous to anthropology. Everyone is advising government – Raymond [Firth], Forde, Audrey [Richards], Schapera. No one is doing any real anthropological work – all are clinging to the Colonial Office Coach. This deplorable state of affairs is likely to go on, because it shows something deeper than making use of opportunities for helping anthropology. It shows an attitude of mind and is I think fundamentally a moral deterioration. These people will not see that there is an unbridgeable chasm between serious anthropology and Administration Welfare work.[15]

VI

British social anthropology flourished as a distinctive intellectual movement for just fifty years, from the early 1920s to the early 1970s. The tradition did not then suddenly come to an end, but it gradually lost its distinctive identity. By the 1980s the debates that had divided Malinowski’s students – and his students’ students – seemed increasingly remote. The functionalist ethnographies began to be taught as classics, not as exemplars.

A variety of internal and external factors undermined the tradition, but the end of the British Empire was decisive. Colonial rule ended in India and Indonesia immediately after World War II. China underwent a revolution. In 1957 Ghana became independent. Within seven years virtually all the African colonies were independent states. A Third World was born.

Having lost an Empire, anthropologists had to find a role. This was not straightforward. Intellectuals charged that they were ‘Orientalists’ who viewed colonial peoples as objects, and constructed false and mystifying differences. Nationalists fretted that their research encouraged tribalism. According to ‘dependency theory’, much favoured by Latin American writers, human lives everywhere were ultimately shaped by multi-national companies. To emphasise local cultural differences was to draw a veil over this deeper reality.

The charge of complicity and complacency was unsettling, but a more serious problem had to be faced. The anthropologists needed to think again about the very nature of their scientific object. Colonial natives had once been loosely identified as Primitives. By the 1970s few British anthropologists were using the old idiom of ‘primitives’ or ‘savages’, except in a fit of absentmindedness, or, like Malinowski, ironically. They no longer seriously believed that there was a distinct category of ‘tribal’ societies, for which a special theory had to be constructed. Yet anthropology was associated with the intellectually indefensible and politically unsavoury idea that the colonial peoples were uncivilized, backward, and very different from Europeans. Few anthropologists addressed these popular misconceptions. Perhaps the old notions had even been rather convenient, since they shielded ethnographers from ticklish questions about why they spent so much time in the colonies.

And yes, many anthropologists did indeed do their fieldwork in Africa, Oceania and the Amazon. A more considered defense of research priorities was now required. If those folk did not represent a different, tribal world, why were they the privileged subjects for ethnographic research? And if social anthropology did not have its special field of research – a particular type of society and culture – then what could it contribute to the broader discourse of the social sciences?

Three possible answers to these questions were floated, perhaps even three and a half, but none was entirely persuasive. The first option was to insist that social anthropologists had indeed honed special methods for doing research in … not, of course, Heaven forbid, ‘primitive societies’. There was a search for euphemisms – pre-literate peoples, or better still, less patronizing, the Other: the non-western. (A popular introduction to social anthropology, published in 1966, was entitled Other Cultures.)[16] In any case, the claim was that when it came to these … Other Cultures … anthropologists could draw on a store of accumulated wisdom. In short, social anthropology did possess its own proper subject matter, even if it wasn’t easy to give it a name.

This was not an unproblematic claim, however, if only because local ethnographers – in Asia and Latin America particularly – were making studies ‘at home’, although usually in the poorest and most marginal communities in their countries. Nevertheless I can testify from my own experience that research students in the early 1960s were firmly given to understand that to win their spurs they had to study foreigners, the more foreign, and the further away, the better. That was the core mission of the discipline. Anyone who insisted on doing fieldwork only or even mainly in Britain risked being exiled to a department of sociology.

A second claim, at variance with the first, was that the ethnographer’s magic could work very well at home, or anyway, quite near to home. After World War II, social anthropologists had ventured into Europe, if only to the periphery, seeking out lineages in a Greek island, or dowry systems in Andalucia, or perhaps describing life in a windswept island somewhere between Scotland and Norway. I remember Edmund Leach returning from a holiday in Portugal in the early 1960s and reporting that he had seen peasants ploughing with bullocks. Someone should go out and study them.

Malinowski’s magic might even be made to work in Britain itself. In 1937 the anthropologist Tom Harrisson launched Mass Observation, which recruited amateur, part-time observers to construct a collaborative popular ethnography of everyday life.[17] (Evans-Pritchard denounced Malinowski as ‘a bloody gas-bag’ because he looked kindly on ‘the mass-observation bilge’.)[18] As Britain’s bombed-out cities were rebuilt after World War II, and new urban communities planned, there was a wave of community studies. A few anthropologists joined in. Raymond Firth and Audrey Richards studied English kinship. At Manchester University, Max Gluckman encouraged some urban research. One of his associates, Ronald Frankenberg, did fieldwork in Wales and published an overview, Communities in Britain, in 1970. However, a general switch to doing fieldwork ‘at home’ could hardly represent a new programme for the discipline as a whole, unless social anthropology were to merge with sociology, bringing as a dowry only its questionable copyright on a particular method of collecting data.

A third answer to the question – what are we doing over there? – was that social anthropology represented the comparative wing of the social sciences. It is obviously worth finding out whether social science theories work in other societies. Do their generalisations apply to human beings in general, or only to citizens of Western liberal democracies? ‘Sociological theory,’ Radcliffe-Brown had pronounced, ‘must be based on, and continually tested by, systematic comparison.’[19] And who but trained ethnographers could put the propositions of the social sciences to the test in other conditions?

A revival of comparative studies was indeed attempted in Britain, but this took a very particular form, a return to the universal histories of the Enlightenment, an ambitious programme that did not really suit the British social anthropologists. It did not fit into the tradition of Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown. And it gave no impetus to ethnographic fieldwork. Yet what were the heirs of Malinowski if they were not ethnographers? Indeed, one last, rather despairing, half-answer to the crisis of identity was to fetishize ethnography. At least that was something they could do, but even here their monopoly was challenged. To their irritation, some eccentric sociologists claimed to do ethnographies, even – such cheek! – ‘ethnographies’ of scientific laboratories and film studios.

At this critical juncture the social anthropologists began to lose ground within their home universities. Britain’s system of higher education began a phase of rapid expansion in the 1960s. New universities were created. But social anthropology did not benefit. Given the requisite political will it might have been possible to establish new departments of social anthropology. As higher education was democratized students were particularly attracted to the social sciences. However, social anthropology remained a small elitist discipline, positioned most securely at Oxford, Cambridge and the LSE. Through the early 1970s undergraduate students in social anthropology were drawn disproportionately from the upper and upper-middle classes.[20] (Both Prince Charles and Prince Andrew read anthropology at Cambridge. At the beginning of the 21st century Prince William followed suit at St Andrews.)

Social anthropologists were employed mainly in the universities, but because very few took their chances in the new universities the profession remained small. Half of all PhDs in the subject were awarded by Cambridge, Oxford and the LSE.[21] By the late 1970s there were only nine departments of social anthropology in the nearly one hundred British institutions of higher education, employing about 150 social anthropologists. At the end of the 20th century, after a generation in which the higher education system expanded enormously, there were fewer than twenty departments and just 230 full-time academic positions in social anthropology in British universities. There were also a number of fixed-term appointments, many of them post-doctoral positions, and a few posts in museums, which might have taken the total to 300.[22]

At the beginning of the 1970s, confidence low, prospects doubtful, the profession had experienced a traumatic demographic transition. The Old Guard bowed out. The students of Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown reached what was then a mandatory retiring age within a few years of one another. They left a diminished inheritance to their successors, the new men (and, eventually, one woman, Jean La Fontaine), who were appointed to their chairs. Some of the most promising younger anthropologists opted for posts abroad in the 1960s and 1970s. The nadir was the 1980s, the decade of Mrs Thatcher’s budget cutting. There were freezes on appointments. University administrations encouraged early retirements. The renewal of the discipline, even its reproduction, seemed to be in doubt.

In the face of these pressures the collective institutions of British social anthropology became bastions of conservatism, not to say reaction.[23] Even in some cases after their retirement, a few elderly professors controlled the national institutions: the anthropology sub-committee of the Social Science Research Council, the Royal Anthropological Institute, the Association of Social Anthropologists, the anthropological section of the British Academy. Sir Raymond Firth was calling the shots in most of the key committees when he was well into his eighties. His close ally Sir Edmund Leach was a major player until shortly before his death in 1989 at the age of 78, although he had insisted in his Reith Lectures that in our ‘runaway world’ ‘no one should be allowed to hold any kind of responsible administrative office once he has passed the age of 55’.[24]

Denied opportunities for patronage, the new professoriate never took effective command. Given the end of Empire, the institutional transition, the decline in opportunities, it was hardly surprising that theoretical debate stagnated and that there was a crisis of intellectual identity.

As if the times were not troubled enough, the social anthropologists were challenged on their own turf, within the universities. Hamstrung by the sclerotic structure of the profession, they were confronted by upstart disciplines that threatened their market position.

In the aftermath of Empire, Western European governments decided to give ‘development aid’ to the former colonies. They set up ministries of overseas development and cast about for academic partners. In response there was a surge of social anthropology in Scandinavia and in the German-speaking countries. In the Netherlands, new departments of ‘non-western sociology’ split off from the old departments of ethnology. The French overseas development ministry funded more Africanist research than the colonial governments had ever envisaged. In Britain, however, Evans-Pritchard and Leach had won their battle against applied anthropology. They were not going to allow a re-run of colonial social welfare research under the name of development. In consequence, any anthropologist who specialised in development studies was unlikely to find encouragement, or employment, in a department of social anthropology.[25]

The rise of sociology presented an altogether more alarming challenge. Sociology was, of course, a well-established discipline in the USA and in many European countries, but until the 1960s it had only a marginal presence in British universities. Then it suddenly took off, encouraged by a Labour government and fuelled by student demand. At Oxford and Cambridge the professors were frankly terrified that their students would desert to this more radical and more relevant social science. Evans-Pritchard wrote to remind the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University that sociology had been taught in the Institute of Social Anthropology since 1910. Perhaps forgetting his apostasy from Radcliffe-Brown’s programme, or perhaps crossing his fingers behind his back, he insisted that ‘social anthropology is and always has been regarded as comparative sociology’. And in a later memorandum to the Vice-Chancellor he suggested, ‘Why not a department of sociology the professor of which should always be a professor of social anthropology?’[26] When at last, in 1969, Cambridge University established a chair of sociology, Meyer Fortes used his political skills to secure the appointment of a social anthropologist, John Barnes.

Bossing the social science faculty at Manchester University, Max Gluckman had encouraged some research in Britain, even on factories and urban communities. Yet he panicked when the university decided to establish a department of sociology. Gluckman’s response was to put up one of his own people, Peter Worsley, for the chair. ‘He appointed me as his pupil – the only concern he had was that sociology wouldn’t overtake anthropology’, Worsley recalled. But this cunning plan couldn’t work. ‘Three quarters of the faculty students wanted to do sociology – we had 700 students, and they only had 40’, Worsley said. ‘I agreed to a limit to expansionism, but Max pushed for more concessions.’[27] There was an acrimonious parting of the ways.

As David Mills notes, ‘no sociologists were offered jobs in anthropology departments, and anthropologists getting jobs in sociology departments were seen as “leaving” the discipline.’[28] By and large, the British anthropologists beat a retreat in the face of sociology. Sociology was about modern, industrial, western societies. Very well, social anthropology was defined as the science of the Rest, the ‘other cultures’. They also stuck to traditional topics of research. Even when their fieldwork took them to societies in the throes of revolutionary change, they typically chose to study cosmologies and kinship systems.

Above all, social anthropology required a fresh theoretical project. The discipline might claim to have its own measure of theory to contribute. After all, anthropologists had ideas about kinship, gender, ritual, classification, taboo, totemism, witchcraft, systems of exchange, patron-client relationships and so on. These were not all pre-modern issues. Many had analogues in all societies. More broadly, culture theory could be identified as an anthropological inspiration, though not perhaps with much conviction on the part of British social anthropologists. And those of a structuralist bent might even aspire to work with neuroscientists to complete the project of Lėvi-Strauss and deliver a comparative account of human ways of thinking.

However, The Sixties, a decade of carnival and radical new ideas – still going strong in the 1970s – was a traumatic period for all the social sciences. The orthodoxies were pummelled, the old authorities ridiculed. The standard theory, structural-functionalism, was denounced as reactionary, impotent in the face of change, an instrument for social control. The old school was not with the movement. A New Left sociologist, Alvin Gouldner, published a famous polemic in 1970 entitled ‘From Plato to Parsons: The Infrastructure of Conservative Social Theory.’[29] Students demonstrating in Paris in 1968 held up banners proclaiming Structures Do Not Take To The Streets. At the very least, there was a need for new ideas about how societies changed – or entered the modern world, as people put it at the time.

Durkheim and his successors had nothing to say about social change or about the economic, political and religious currents that swept across national boundaries. Yet while the ethnographer might still be working in a remote village, the villagers were usually well aware that they lived in a larger world. The classical models tended to ignore this fact and to assume that societies and cultures coincided, and that their boundaries were real and rigid, and that they were in a state of equilibrium (though there were exceptions, notably Evans-Pritchard’s study of the Sanuni of Cyrenaica, Leach’s of the Kachin and Ernest Gellner’s of the Berbers of the Atlas mountains in Morocco).[30]

These weaknesses made social anthropology vulnerable to a Marxist critique. Competitive Marxist anthropologies emerged in Paris in the 1970s. Some British scholars were interested, even excited by these new ideas. A Marxist cargo cult swept students in University College London and caught up some of the staff. A radical journal, Critique of Anthropology, was launched. Then very suddenly, in the mid 1980s, Glasnost broke out. A few years later the Soviet Empire imploded. The mood changed in the West. There was a shift to a more personal politics, a politics of identity and representation. ‘Culture’ became a key word, and within European anthropology some came to feel that perhaps, after all, American anthropology had been right to take ‘culture’ as its subject rather than social structure.

Clifford Geertz was renewing the project of interpretive anthropology, and refining – and cutting back – the notion of culture. In the 1990s interpretive anthropology seemed set for a while to sweep the board on both sides of the Atlantic. Even in its British heartlands, social anthropology barely resisted translation into cultural studies (yet another new discipline to threaten their identity).

However, the culturalist discourse excluded much that had been central to the social anthropology. Politics was treated simply as rhetoric. Ethnic identity was merely an ideological construction. Religions were reduced to cosmologies. Kinship was a symbolic statement about shared identity, not a system of working connections on which people depended for dear life. Economics was about conceptions of nature, production and reproduction, but excluded such mundane factors as land law, labour, budgets, or calculations of profit and loss. Ethnographies were, at best, tentative essays in the difficulties of inter-cultural communication.

There is a profound gulf between the culturalists and those anthropologists who regard themselves as social scientists. From the idealist point of view of the culturalists, cultures are apparently very different, even incommensurate. Indeed, the culturalists celebrate the very various ways in which people think about the world. But social anthropologists are interested in the conditions and organization of daily life. They are impressed rather by the recurrence of certain institutions, the limited range of variation, the very common strategic responses to the problems of getting by, making do, rubbing along. An anthropology that situates itself in the social sciences would have a very different agenda to the culturalist programme.

While comparisons may be difficult they are not impossible, and there is very real need for broader perspectives and for better information about how other people manage their lives. Very nearly all research funding in the human sciences is directed to the study of the inhabitants of North America and the European Union. Ninety-six per cent of the subjects of studies reported in the leading American psychology journals are drawn from Western industrial societies.[31] These represent a minuscule and distinctly non-random sample of humanity. The leading economics journals publish more papers dealing with the United States than with Europe, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa combined, according to a report in the Economist. And it is a science of the rich. ‘The world’s poorest countries are effectively ignored by the profession’, the report noted.[32]

And so new projects are emerging, on a wider stage. The European Association of Social Anthropologists was set up in 1989, coincidentally just before the walls that had divided Eastern and Western Europe fell. It has flourished since. A new community of European social anthropologists is becoming more significant than the national traditions that it encompasses. The younger generation shares the classic commitment to Malinowskian fieldwork, but draws on a range of sociological and historical discourses. They engage with European concerns about immigration and ethnicity, but many do fieldwork in societies beyond Europe. At the same time, social anthropology is making a comeback in some North American departments of anthropology, and there are other vibrant centres, notably in Brazil, India and Japan. A more cosmopolitan discipline is emerging, multi-centred, engaged in a range of current intellectual debates. The social science tradition is reasserting itself.

But it is not structural-functionalist. The theories of the previous decades are seldom invoked, yet young social anthropologists read widely and reflectively in social theory. Their arguments are closely tied to detailed ethnographic observations, but their ethnographies do not describe isolated, bounded, traditional, monocultural societies. Rather, the most exotic communities are presented as part of the wider world, the site of intellectual and political cross currents, echoing to debates and dissension. The most apparently traditional societies are not presented as unchanging, or as mysteriously, or enchantingly, ‘other’. In order to make sense of their world, even the most conservative and apparently isolated people appeal to shifting frames of reference. Magic and religion often appear to be no less pragmatic than bio-medicine. Adepts of strange cults turn out to be no less reasonable than we ourselves. Nor is this all taken to be a sign of modernity, or a marker of uncomfortable and ill-comprehended change, to be blamed perhaps on a vaguely conceived Neo-Liberalism. Rather, it is the normal state of things, everywhere, at all times. As social anthropology becomes a truly cosmopolitan discipline, a new realism is abroad.[33]

- [1]To be published in October 2014 by Routledge under the title Anthropology and Anthropologists: The British School in the Twentieth Century.↩

- [2]The following paragraphs are drawn from Adam Kuper, ‘Post-modernism, Cambridge and the great Kalahari debate’, Social Anthropology, 1992, 1 (1a): pp. 57-71.↩

- [3]Audrey Richards, ‘The concept of culture in Malinowski’s work’, in Raymond Firth (ed.) Man and Culture: An Evaluation of the Work of Bronislaw Malinowski, London, 1957, p. 19.↩

- [4]Hortense Powdermaker, Stranger and Friend, London, 1966, p. 36.↩

- [5]Siegfried Nadel, Anthropology and Modern Life, Canberra, 1953, p. 13.↩

- [6]Edward Said, Orientalism, New York, 1978.↩

- [7]An influential volume of critical essays edited by Talal Asad, Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter, was published in London, in 1973.↩

- [8]See, e.g., Peter Pels, ‘Global “experts” and “African” minds: Tanganyika anthropology as public and secret service, 1925-1961’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17, 2011, pp. 788-810.↩

- [9]See a special issue of Anthropological Forum (1977), entitled Anthropological Research in British Colonies: Some Personal Accounts.↩

- [10]Benôit de L’Estoile, ‘From the Colonial Exhibition to the Museum of Man. An alternative genealogy of French anthropology’, Social Anthropology, 2004, 11: pp. 341-361, citation p. 343.↩

- [11]A. I. Richards, ‘Practical anthropology in the lifetime of the International African Institute’, Africa, 1944, p. 295.↩

- [12]Loc cit, p. 292.↩

- [13]B. Malinowski, ‘Native education and culture contact’, International Review of Missions, 1936, 25: pp. 480-515, quote p. 502.↩

- [14]Malinowski memo for a meeting with Lugard and Oldham, 1930, cited by Helen Tilley, Africa as a Living Laboratory, Chicago, 2011, p. 268.↩

- [15]Cited in J. Goody, The Expansive Moment

The rise of Social Anthropology in Britain and Africa 1918–1970, Cambridge, 1995, p. 73.↩ - [16]John Beattie, Other Cultures: Aims, Methods and Achievements in Social Anthropology, London, 1966.↩

- [17]Nick Hubble, Mass-Observation and Everyday Life, Basingstoke, 2006.↩

- [18]Cited in Jack Goody, The rise of Social Anthropology in Britain and Africa 1918–1970, Cambridge, 1995, p. 74.↩

- [19]A. R. Radcliffe-Brown, ‘The comparative method in social anthropology’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 1951, p. 16.↩

- [20]David Mills and Mette Louise Berg, ‘Gender, disembodiment and vocation: Exploring the unmentionables of British academic life’, Critique of Anthropology, 2010, 30 (4), p. 338.↩

- [21]Jonathan Spencer, ‘British social anthropology: A retrospective’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 2000, p. 10.↩

- [22]David Mills,‘Quantifying the discipline. Some anthropology statistics from the UK’, Anthropology Today, 2003, 19 (3): 19–22.↩

- [23]David Mills, ‘Professionalising or popularising anthropology? A brief history of anthropology’s scholarly associations in the UK’, Anthropology Today, 2003, 19 (5): 8–13.↩

- [24]E. R. Leach, Runaway World? London, 1968, pp. 73-74.↩

- [25]Ralph Grillo, ‘Applied anthropology in the 1980s. Retrospect and prospect’, in R. Grillo and A. Rew (eds.), Social anthropology and development policy. New York, 1985.↩

- [26]Cited in David Mills, Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology, Oxford, 2008, p. 110.↩

- [27]Ibid, p. 109.↩

- [28]Ibid, p. 111.↩

- [29]Alvin Gouldner, The Coming Crisis of Western Sociology, New York, 1970.↩

- [30]E. E. Evans-Pritchard, The Sanusi of Cyrenaica, Oxford, 1954; E. R. Leach, Political Systems of Highland Burma, London, 1954; Ernest Gellner, Saints of the Atlas, London, 1969.↩

- [31]J. J. Arnett, ‘The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American’, American Psychologist, 2008, 63: pp. 602-614.↩

- [32]‘The useful science?’, Economist, January 4th, 2014.↩

- [33]I am biased, however. See my paper, “Culture, Identity and the Project of a Cosmopolitan Anthropology”, Man, New Series, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Sep., 1994), pp. 537-554.↩

Please join our mailing list to receive notification of new issues